NB. Clicking on an image will open a higher resolution image

The Origins of the Walter Family in Normandy

Theobald Walter was granted the hereditary title of 1st Butler of Ireland in the late 12th century, and subsequent generations adopted the surname 'Boteler' or Butler.

A diverse number of pedigrees compiled in the past have claimed various exalted ancestors for the Butlers, none of which have been proven. Various respected peerage publications exemplify the widely varied theories of the origins of this family:

Debrett’s Peerage (1825), states that ‘the original descent has been variously deduced: Herveius a companion of William the Conqueror; a younger son of the house of Clare; or, Walter, son of Gilbert Becket brother of Thomas á Becket Archbishop of Canterbury’.

Burkes ‘Peerage and Baronage’ (1st pub 1826, London) states that ‘Hervey Walter was heir to Hubert Walter who is mentioned in the Sheriff’s account for Counties Norfolk and Suffolk 3 Henry II, 1158.’ (this erroneous theory will be explored in detail)

‘The Baronage of England after the Norman Conquest’, by Sir William Dugdale, King of Arms (London 1675), also referred to the record in ‘3 Henry II’ (Pipe Roll)- Dugdale concluded: ‘upon the Sheriff’s accompt for Norfolk and Suffolk mention is made of Hubert Walter in those Shires, from whom succeeded Hervey Walter’. (again, an erroneous theory)

George E. Cokayne in his ‘The Complete Peerage’ (pub 1887-1896) did not even attempt to explain the possible ancestry of Hervey Walter.

The following analysis looks at the likelihood of the various ancestral origins claimed in numerous pedigrees produced through the centuries, and any evidence found.

ANALYSIS OF THE VARIOUS THEORIES OF THE ORIGINS OF THE WALTER FAMILY

As

discussed, various pedigrees compiled over several

centuries, have claimed various exalted ancestors for the Butlers, none of

which have been proven. As evidence shows, Hervey was the name of the earliest

known ancestor of the Butlers, born c.1080’s in Suffolk. And his son Hervey

Walter was the father of two sons who reached exalted positions, Theobald

Walter appointed first Butler of Ireland, and Hubert Walter who would become

the most powerful man in England under the King, as Chief Justiciar, Archbishop

of Canterbury and Chancellor. It should also be remembered that the Walter

family owed their rise in status to their uncle Rannulf de Glanville who also

rose in status after his promotion to Chief Justiciar under Henry II.

The

lands held by the Walter family in Suffolk were linked with the powerful

tenant-in-chief Robert Malet in the Domesday Book (1086), and this association

should be kept in mind.

The following analysis looks at the likelihood of the various ancestral origins claimed in numerous pedigrees produced through the centuries, and the evidence found on each theory.

(i)

the de Clares

(ii)

the Beckets

(iii)

the de

Glanvilles

(iv)

Hervey de

Bourges and Hubert de MonteCanisy

1.THE de CLARES

Although there is no evidence to support such a claim, some researchers in the past have concluded that the Butlers and Walters descended from the de Clare family and their ancestors the Counts of Brionne.

The first to canvas the suggestion that the Ormondes descended from Henry I’s cupbearer, Gilbert fitzRichard de Clare, were William Roberts, Ulvester King of Arms in Ireland in 1644, supported by Rev. John T. Butler of Northants in the 1676-85, although it first appeared in print in a book entitled “Some account of the Family of the Butlers” printed in London by John Morphew in 1716, and it was accepted by the pedigree and peerage writers of the 18th century, and many more recent publications and online family trees have copied this unsubstantiated ancestry, but, as Butler historian Theobald Blake Butler claimed, no serious proof has ever been produced with regard to it.

Gilbert fitzRichard was the son of Richard fitzGilbert de Clare (1035-1090) whose father Gilbert Count of Brionne and Eu was one of the early guardians of Duke William of Normandy in his minority, before he was murdered. Gilbert Count of Brionne’s father was Geoffrey Count of Eu, the illegitimate child of Richard I of Normandy (King William’s great grandfather).

Richard fitzGilbert married Rohese de Giffard daughter of Walter Gifford of Bolbec, Lord of Longueville, Normandy, a Norman baron who was one of the loyal supporters and known companions of William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings. Walter Gifford was one of the Norman magnates, who personally provided 30 ships for William’s invasion fleet. Walter’s grandmother was sister of Gunnor Duchess of Normandy (wife of Richard I of Normandy, and both daughters of King Harold I ‘Bluetooth’ Gornsson of Denmark) and as such was a relation of William. Gifford was granted 107 lordships as tenant-in-chief, 48 of which were in Buckingham which his son Walter inherited by 1085 and became 1st Earl of Buckingham.

As the de Clare family are well documented due to their relationship to William the Conqueror and his Norman ancestors, and held very high status in the Norman hierarchy, it would therefore seem unlikely that Theobald and his brother Hubert Walter’s ancestry and de Clare heritage would be undocumented and lost to history, given their own subsequent high status in the courts of Henry II and his sons and heirs Richard and John, particularly Hubert in his appointed roles as Archbishop of Canterbury and Chief Justiciar of England.

The Walters did not hold any lands previously held by Richard fitzGilbert de Clare in the Domesday survey. Richard fitzGilbert was well rewarded for his services to King William with grants of large quantities of land, as revealed in the Domesday survey. As tenant-in-chief, Richard fitzGilbert held 186 lands, including 86 lands in Suffolk, 49 in Essex (including Great and Little Dunmow), 36 in Surrey, and nine lands in other counties (Middlesex, Cambridgeshire, Devon, Bedfordshire and Wiltshire). He was also named as sub-tenant/lord in 1086 to 144 lands including some of his own and 33 in Kent held from Bishop Odo of Bayeux and the Archbishop of Canterbury. None of his Suffolk lands were later held by the Walter family.

It is also unlikely that the link could be through one of the lesser status younger sons/grandsons, as the connection with this highly ranked family would still have been documented.

Richard fitzGilbert de Clare had several sons including:

1.Roger fitzRichard- inherited the lands in

Normandy

2.Walter de Clare Lord

of Nether Gwent Wales, 1058-1138; founder of Tintern Abbey; dispute over

whether he married, but left his estates to a nephew (son of Gilbert)

3.Gilbert ‘fitzRichard’ Lord

of Clare, Earl of Hertford born 1054 at Clare, Risbridge, Suffolk and died in

Wales c.1117 as Lord of Cardigan, who married Adeliza de Clermont (m.2.

__de Montmorency, possibly named Bouchard or Hervey) and had several sons

including-

(A)Sir Richard

‘fitzGilbert’ Lord of Clare (1094-1136)

whose sons Gilbert ‘fitzRichard’ and Roger ‘fitzGilbert’ granted titles 1st

and 2nd Earls of Hertford;

(B)Gilbert

‘fitzGilbert’ 1st Earl of Pembroke (1100-1149) father of Richard 2nd Earl of Pembroke,

known as Strongbow, who invaded Ireland in 1170 (his daughter Isobel married

William Marshall 4th earl of Pembroke).

(C)Walter de

Clare died 1149 -little known, but

does appear in records with brother Gilbert- no record of any marriage or issue

(NB. born too late to be father of Hervey b.c.1080’s);

(D)Baldwin

fitzGilbert, Lord of Bourne, born Risbridge, Suffolk, d.1171 Bourne.

Lincolnshire;

4.Robert ‘fitzGilbert’ de Clare born 1064 Tunbridge, died 1136 Little Dunmow, Essex,

(married Matilda de St Liz, b.1093 Huntingdon, so, thirty years younger than

her husband), father of Walter fitzRobert Lord of Dunmow Castle (1124-1198) succeeding to his

father’s position of steward under King Stephen. Walter witnessed Hubert

Walter’s foundation charter for West Dereham Abbey in 1188.

5.Richard fitzRichard born 1062, died 1107, Abbot

of Ely

6.daughters: Avise m.1. Robert Lord of ‘Belvoir and

Stafford’ de Toeni; Rohese (de facto).1.

Eudo ‘le Dapifer’ de Rie, 2. Hughes l’comte de Damm Montdidier; Hawise m. Raoul I de Fougeres; Elizabeth m. Eustace Bourne

There have been erroneous suggestions of a son of Gilbert fitzRichard named Hervey, sometimes attributed as the ancestor of the Butlers.

Firstly,

if there had been such a son, he would have been born too late to have been the

father of Hervey Walter ( who was born c.1110).

Secondly,

there are no records of a Hervey de Clare, son of Gilbert fitzRichard de Clare.

The idea probably stemmed from a record of a Hervey listed with his ‘brothers’

Gilbert fitzGilbert, Walter and Baldwin as witnesses to a charter to Thorney

Monastery in Cambridgeshire by their mother Adeliza de Clermont, wife of

Gilbert fitzRichard de Clare, but was actually a younger half-brother by their

mother’s second marriage.

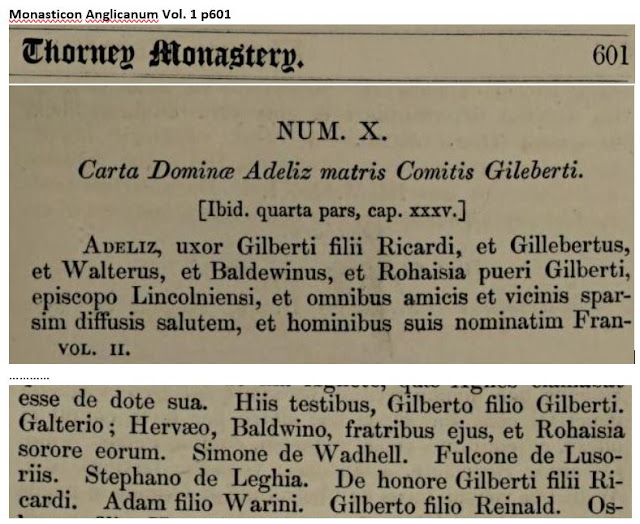

Monasticon Anglicanum, v.1, p.601:

Thorney Monastery (Cambridgeshire) – Number X- Dated c.1137

Charter

of Lady Adeliz mother of Count Gilbert (fitzGilbert)

Adeliz, wife of Gilbert fitz Richard, and

Gilbert and Walter and Baldwin and Rohesia children of Gilbert, …

Witnesses,

Gilbert son of Gilbert. Walter, Hervey, Baldwin, his brothers, and

Rohesia their sister.

Gilbert

fitzRichard died c.1114-1117, and his widow Adeliza remarried to a man

variously named de Montmorency or MountMoraci or MountMaurice, by whom she had

a son named Hervey de Montmorency who accompanied his nephew Richard de

Clare (son of Gilbert fitzGilbert) known as Strongbow, to Ireland in 1170, and

was appointed Constable of Ireland in 1172, married Nesta daughter of Maurice

fitzGerald, and retired to a monastery (Trinity, Canterbury) dying without

issue, according to the contemporary historian Giraldus Cambrensis/Gerald of

Wales, in his ‘Expugnatio Hibernica’ (p.120) who named him Hervey de

Mountmaurice/’heruy of Mountynorthy’. Giraldus Cambrensis noted that “not

one of the four Pillars of the Conquest of Ireland, namely Robert fitzStephen,

Hervey de Montmaurice, Reymond le Gros and John de Courcy, ever had children of

their espoused wives”. He stated that Hervey was paternal uncle

to Earl Richard (Strongbow). He also gave a very unflattering description of

Hervey’s personality and morals, indicating some personal animosity. Hervey’s

charter for the foundation of the convent of Dunbrothy (Dunbrody, Co.

Wexford, Ireland) named him as ‘Hereveius de Monte Moricii’.

It

is probable this charter of ‘Adeliza de Monte Moraci, domina de Deneford’

is the only documentary source that lists ‘Hervey’ as a brother of Gilbert

fitzGilbert, and therefore the inclusion of a son named Hervey ‘de Clare’

in the de Clare family history may have been incorrectly interpreted by past

researchers for Hervey ‘de Montmorency’, son of Adeliza by her second

husband, and therefore only a half-brother to Gilbert fitzGilbert, Walter and

Baldwin de Clare, Adeliza’s sons by her first husband Gilbert fitzRichard.

Based

on this charter document, there was no son of Gilbert fitzRichard de Clare

named Hervey de Clare, only the much younger Hervey de Montmorency, born after

1117, and therefore could not be the father of Hervey Walter.

Nor

could either of the Walter de Clares be an ancestor of the Butlers- Walter the elder left no male heirs, and Walter the younger was born too late to be the father of Hervey [Walter].

A further argument against a descent from the de Clare family- Hervey Walter and son Theobald adopted the same coat-of-arms as the de Glanville family (a chief indented, azure). If Hervey was closely related to the de Clare family, one would expect that they would have adopted the same coat-of-arms (three red chevrons on a gold background) as this illustrious family of de Clare to gain royal favour, not chosen the coat-of-arms of the lesser middle status de Glanville family.

In my opinion, the theory of descent from the de Clare family is highly improbable, due to lack of any evidence linking the families, nor any suitable de Clare family candidates, and the high status held by the de Clare family (and their marital partners) in comparison to the initial status of middling knights such as the Walters.

2.THE BECKETS

For many centuries there was speculation that Theobald Walter may have been related to the Becket family in some way. Gilbert Becket, and his siblings must have been born in the 1090’s, so would have been of a similar age to Hervey.

Legend has it that the family’s promotion in the

Court of Henry II was due to Henry’s repentance for the assassination murder of

Thomas à Becket on the altar of Canterbury Cathedral by Henry’s knights.

However, this relationship is not a proven fact, and is disputed by some

researchers.

Theobald Blake Butler points out, that ‘this particular claim rests on entirely different grounds to any of the others in that it is the only descent which a head of the house of Butler has claimed for himself. This ancestry was apparently first put forward by James 4th Earl of Ormond in the year 1444, when he procured an act of parliament establishing his descent from Agnes Becket, sister of the martyred Archbishop Thomas. This earl was a great lover of heraldry and gave land for ever to the College of Heralds. He (sic. –only his wife, and his son Thomas 7th E. of O.) was buried in the hospital of St Thomas of Acre in Cheapside, which was founded by Agnes Becket apparently after the death of her husband, Thomas FitzTheobald de Helles c.1190.

This earl is the first (sic) of the Butlers to be buried there and it is probable that he chose this site for his tomb to strengthen his claim to a descent from the Beckets. The Earls of Ormond continued to maintain their Becket ancestry down to the end of the 17th century and various pedigrees are to be found in Carte’s ‘Life of Ormond’ which were compiled during that period and, though contradictory, all uphold the same ancestry.

The actual descent generally claimed is that one,

Thomas de Helles, who undoubtedly married Agnes, sister of Thomas Becket, was

the ancestor of the Butlers. Now, it is certain that the Butlers do not

descend from the Beckets, either in the male or female line.’

(also see ‘Some account of the Hospital of St.

Thomas of Acon in the Cheap, London’, by Sir John Watney, 2nd

ed. 1906, pp.8-11, 47-50)

Theobald Blake Butler also wrote an article, ‘The Butler-Becket Tradition’, that was reproduced in the Butler Society Journal (V.2, No.4, p.424), in which he states:

The first occasion that a definite claim was put

forward officially was made by James 5th Earl of Ormond in 1454 and

is printed in the Parliamentary Rolls V.5 p.257. This descent, namely that the

Earls of Ormond ‘were lineally descended of the blood of the glorious martyr St

Thomas sometime Archbishop of Canterbury’ does not appear to have been

questioned until 1682 when the Rev. John Butler, rector of Lichborough

Northants and chaplain to James 1st Duke of Ormond compiled a

descent for the family from the de Clares, which was apparently accepted until

the 20th century when several different ancestries have been

propounded.

The late Walter Rye was convinced that the Beckets

were descended from the De Valoines family but was not able to produce

sufficient proof to establish these relationships. (viz. that Thomas de Helles

was a son of Theobald de Valoines, Lord of Parham)

Since Walter Rye wrote in 1924, the late Dr William

Farrer has published ‘The Early Yorkshire Charters’ and in Vol. 5 pp.234-238 he

gives considerable detail of the Valoines of Parham family in which he shows

that their descent was from Hamo de Valoines an undertenant of Count Alan of

Brittany both in Suffolk and in Yorkshire.

Blake Butler then speculates that, 'the pedigree

allows for Theobald Walter I marrying the daughter of Thomas fitzTheobald de

Helles (de Valoines) and Agnes Becket, (who would be his cousin germain and for

which dispensation would be required in those days)'.

Editorial Note (Butler Society)- The late

Theobald Blake Butler’s account, largely speculative, is based on W. Rye’s

work with amendments of the Valoines pedigree given by W. Farrer in his Early

Yorkshire Charters (v). He was not able to consult Davy’s MSS of Suffolk in the

British Museum. He sent this copy, as revised in 1960, to Lord Dunboyne who has

kindly enabled it to be printed here.

Another early reference to this ancestry seems to have originated from Sir Robert Rothe barrister-at-law and council to Thomas 9th Earl of Ormonde in Queen Elizabeth’s time, who drew up an account of the origin and descent of this family from ‘Walter fitzGilbert’ son of Gilbert Becket. (Carte) There is no record of a Walter fitzGilbert, and if there had been, he would have been contemporary with Hervey Walter, and therefore born far too late to be ancestor of the Walter family.

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas à Becket was born 1119-1123 in Cheapside, London, to Gilbert and Matilda Beket (who may have had the pet name of Roheise).

Gilbert Becket took part in the first expedition to

the Holy Land in 1099. After having been held prisoner ‘for a year and a

half among the Infidels’, he returned to England. Brompton in his Chronicle

(1163) says that ‘Gilbert, immediately after his marriage made a second

voyage to the Holy Land, leaving his wife with child, Thomas Becket, and staid

three years and a half in that country. After his return he had… two daughters’

[Agnes and Mary, Abbess of Barking]- therefore they could not have been born before

1124.

Gilbert’s father was from Thierville in the

lordship of Brionne, Normandy and was either a small landowner or a rural

knight. Gilbert was perhaps related to Theobald of Bec whose family also was

from Thierville and was chosen by King Stephen to be archbishop of Canterbury

from 1138 to 1161. Theobald of Bec was the patron of his successor Thomas

Becket who was appointed archbishop in 1162, until his infamous murder in 1170.

Thomas’ mother, Matilda, was supposedly also of

Norman descent and her family is said to have originated near Caen. However,

another legend has it that, ‘Gilbert, whilst in captivity, had been the

instrument of converting the daughter of a Sarazen Commander to the Christian

faith, who afterwards, making an escape, came to England, found out Gilbert,

was baptised and married him’. Which story is true is not known.

Gilbert began his life as a merchant, but by the

1120’s he was living in London and a property owner, living on the rental

income from his properties. He also served as the sheriff of the city at one

point at the height of his prosperity. But later, he suffered heavy losses when

his properties were destroyed by fire. They were buried in Old St Paul’s

Cathedral.

Thomas Becket was their only son and heir. They had four daughters

including Agnes who became Gilbert’s heir and descent continued through her

marriage to Thomas fitzTheobald de Helles/Heilli (of Hills Court, Kent, near

Darenth), and Thomas’ ancestry remains a mystery.

The family house in Cheapside which was reckoned to be the site of

Thomas’s birth, remained in the hands of his sister Agnes, and gained cult

status. In 1227/8 the site of St Thomas’s birth was granted by Thomas de Helles

to the master and knightly brothers of the Hospital of St Thomas of Acre for

the foundation of a hospital. The community was an order of Hospitallers

dedicated to St Thomas which had been established in Acre in 1191/2 with the

support of King Richard.

Thomas Carte discusses the de Helles’ potential relationship to this family in the Introduction to his book on the Duke of Ormonde [A History of the Life of James Duke of Ormonde, in 2 volumes, pub 1736, v.1., p.xxxiv+]. According to Carte, Theobald Walter held the lands of Helles/Heilii, ‘proving’ a close relationship, however, this has not been substantiated by other evidence. As suggested by Theobald Blake Butler, maybe Theobald’s first wife was a daughter of Thomas de Helles and Agnes Becket.

Theobald Walter’s only known issue from his unnamed

first marriage was a daughter named Beatrix Walter who made several grants to

the Abbey of St Thomas in Dublin, of lands, churches and advowsons in the land

of Ely “or Helii” which Theobald Walter had given her in marriage to

Thomas de Hereford.

In ‘The Letters from Theobald Blake Butler to

Lord [Patrick] Dunboyne-Draft’ (released by the Butler Society, and John

the Lord Dunboyne), Theobald discusses the various theories, but could not

produce any proof (see Letters, pages 97, 99-100).

The main sources for the life of Becket are a number of biographies written by his contemporaries. (ref: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: Becket, Thomas, by Frank Barlow, 2004)

Apart from legend, and the claims of the 4th and/or 5th Earls of Ormond in the 15th century, there is little, if any, unequivocal evidence of an association between the Walter family and the Beckets, and the promotion of the Walter family during the reign of Henry II and his sons, particularly Hubert Walter's promotion as Archbishop of Canterbury which can be attributed to their relationship with the de Glanville family, and King Richard's admiration for Hubert Walter's skills on the Crusade and Richard's subsequent captivity. There is also no evidence that Thomas de Helles was of the Valoines family, as claimed by Walter Rye (antiquarian who wrote 80 books on Norfolk in the late 19th century). And most importantly, the chronology of the two families does not correlate.

3.THE de GLANVILLES

This is the most interesting theory, as there are significant parallels between the two family pedigree lines of ‘Herveys’ living in co. Suffolk at the same time in the 12th century. There were two men named Hervey born in the 1080’s in Suffolk, viz. Hervey (Walter) the elder, and Hervey de Glanville senior, and they both had sons named Hervey viz. Hervey Walter and Hervey de Glanville junior both born c.1110, and the two families were closely associated throughout the 12th century. Some have speculated that Hervey Walter, father of Theobald and Hubert, was also Hervey de Glanville junior, and this theory cannot be dismissed.

But before we look at the de Glanville family in detail, we need to revisit the two prime records we have on the Walter family to see how they could be linked with the de Glanvilles.

Two documents exist revealing that Theobald Walter’s grandfather, the earliest known ancestor of the Irish Butlers, was named Hervey.

The

first was an accord between Theobald Walter and William fitzHervey in 1195 over

ancestral lands, in which Theobald’s grandfather (Latin ‘Aui’) is named

as Hervei Walteri, the same name as Theobald’s father.

Feet

of Fines (reign of Henry II and first seven years of reign of Richard I A.D.

1182-1196),

1894, Pipe Roll Society, p.21) (full record copy in blog chapter, Part 1, on Ancestors Origins

of Theobald Walter)

The

point that stands out in this record is that the justices hearing the case in

the King’s Court were led by Theobald’s brother Hubert Walter, Chief Justiciar

and Archbishop of Canterbury at that time. As Hubert would oversee the legality

of this document, it is unlikely that a mistake would be made by a cleric

naming their mutual grandfather, although it should be noted that this copy

would have been a later redraft of the earlier original document.

The second record occurs in A.D. 1212 in an’ Inquest of co. Lancaster’ (an inquiry into tenures and alienations), about a century after the birth of Theobald’s father Hervey Walter. This record indicates that it was Theobald’s grandfather named ‘Hervey’ (father of Hervey Walter) who was granted the fee of Weeton and surrounding lands in the Hundred of Amounderness, Lancashire, during the reign of Henry I (ie.1100 to 1135). This reaffirms that Theobald’s grandfather was definitely named Hervey, but the question of whether he was also named Hervey Walter, remains uncertain.

‘Testa de Nevill’, (Liber

Feodorum- Book of Fees), Part I, A.D. 1198-1242, (London 1920), fol. 818 p.211

Translation in ‘Lancashire Inquests, Extents, and Feudal Aids, A.D.

1205-A.D. 1307’, edit by William Farrer (Record Society 1903), p.37:

The

lands granted to Orm son of Magnus in marriage c.1130’s with Hervey’s

daughter Alice, in Rawcliffe, Thistleton and Greenhalgh, were all part of the

Amounderness fee in the Honour of Lancaster (Lancashire) held by the Walter

family. Orm’s relationship with Warin Bussel Lord of Penwortham who held lands

in Lancashire and Cheshire, and Bussel’s relationship with Hervey de Glanville

will be explored in detail later.

The question that has frustrated researchers down the centuries -

Why

was Hervey of Co. Suffolk, granted the Amounderness fee in Co. Lancashire?

There

are no contemporary records that show any particular relationship between

Hervey Walter (the elder) and King Henry I or his nephew and heir Stephen Count

of Mortain who held the Honour of Lancaster, or that shows he was anyone of

note in Norman society and thereby deserving of a grant of land. It would

appear, from the lack of records, he was just an undistinguished knight in the

county of Suffolk, possibly a younger son. However, a

contemporary named Hervey de Glanville, a distinguished knight and baron from

Suffolk, was closely associated with the court of Henry I, and in particular

with Stephen as Count of Mortain and afterwards when Stephen succeeded to the

throne. He was also associated with the Bussels, Lords of Penwortham who originally held Amounderness.

Was this Hervey de Glanville the

catalyst for the Walter family’s acquisition of the Amounderness lands, and on

what basis?

Was there a long-term close relationship between Hervey de Glanville and Hervey [Walter] the elder, either by blood, or did the relationship date back to their families in Normandy, pre-Conquest?

As suggested in the chapter on the ‘Origin of the Surname Walter’, the Walter (or Walter the crossbowman) who held lands in Bishops Hundred in Suffolk in the Domesday survey of 1086, may have been the Norman ancestor of the Walter family. On his death, did either Hervey de Glanville or his elder brother William de Glanville (as heirs of Robert de Glanville) hold custody of Walter’s underage children, which could explain the close relationship between the Walter family and the extended de Glanville clan? Robert de Glanville held some of the same lands as Walter in Bishops Hundred, from Robert Malet.

The theory that has been suggested by some historians, was that Hervey de Glanville was also Hervey [Walter] the elder.

The de Glanville family link

A ‘Sire de Glanville’ accompanied William the Conqueror in his conquest of England in 1066, and his descendant or relation, probably a son, Robert de Glanville was well rewarded with 18 lands in Suffolk and one in Norfolk, as an undertenant of tenant-in-chief, Robert Malet, as shown in the Domesday Book of 1086.

The

Malets and de Glanvilles held ancestral lands in the same area of Normandy, and

would have had a long-standing close association.

A later descendant, Rannulf de Glanville, Chief Justiciar of England under Henry II, and son of Hervey de Glanville, held a very close relationship to the Walter family, and researchers attribute the rise of the Walter family to this close relationship.

Rannulf

held the most powerful position in England, and was one of Henry’s closest

advisors, so much so that he entrusted the education of his son Prince John to

Rannulf. Rannulf was also entrusted with the education of his nephews Theobald

Walter and, in particular, Hubert Walter. Hubert would work closely with

Rannulf learning about the law, and in turn would be appointed Chief Justiciar

by Richard I, as well as being elected Archbishop of Canterbury and Papal

Legate, making him even more powerful than his uncle had been, as Richard was

rarely in the country and the running of the country was left in the hands of

Hubert. Theobald developed a close association with Prince John, probably when

John was part of the de Glanville household. He and Rannulf accompanied John to

Ireland in 1185, being richly rewarded, and Theobald would witness many of

John’s charters indicating he was frequently part of his entourage. Charters

indicate he was John’s personal butler before he was granted the hereditary

title of Butler of Ireland. When John succeeded to the throne, he would appoint Hubert Walter as his Chancellor.

It is well established that Rannulf and Hervey Walter’s wives were sisters, daughters of Theobald de Valoines of Parham in County Suffolk. However, some researchers have questioned the degree of closeness of that relationship, whether just marital or also biological.

We need to explore the available records to see if this theory is plausible, although it must be acknowledged that it is not possible to prove it beyond doubt due to minimal records during this period of time.

Pollock and Maitland in their “History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I”, (v.1, p.162, 1898, 1903), summarized Ranulf de Glanville’s life:

Ranulf

de Glanvill came of a family which ever since the Conquest, held lands in

Suffolk; it was not among the wealthiest or most powerful of the Norman houses,

but was neither poor nor insignificant. Probably for some time before 1163 when

he was made sheriff of Yorkshire, he had been in the king’s service. The

shrievalty of Yorkshire was an office that Henry would not have bestowed upon

an untried man; Glanville held it for seven years. In 1174, being then sheriff of

Lancashire and custodian of the honour of Richmond, he did a signal service to

the king and the kingdom. At a critical moment he surprised the invading Scots

near Alnwick, defeated them and captured their king. From that time forward, he

was a prominent man, high in the king’s favour, a man to be employed as

general, ambassador, judge and sheriff. In 1180 he became chief justiciar of

England, prime minister, we may say, and viceroy. Henry seems to have trusted

him thoroughly and to have found in him the ablest and most faithful of

servants. Henry’s friends had of necessity been Richard’s enemies, and when

Henry died, Richard, it would seem, hardly knew what to do with Glanville; he

decided that the old statesman should go with him on the crusade. To Acre, Glanvill

went, and there, in the early autumn of 1190, he died of sickness.

Historian, Richard Mortimer, authored an article on “The Family of Rannulf de Glanville” (an ‘academia.edu’ article, Vol. LIV No 129, May 1981), in which he wrote:

‘The

family of Rannulf de Glanville are an example of a ‘new’ family advancing in

the service of Henry II and his sons…. Various attempts have been made to

reconstruct the Glanville family. Rannulf was not a member of the senior branch.

As is now known, his father was Hervey de Glanville, one of the heroes of the

siege of Lisbon on the Second Crusade and a respected worthy of the county

court.

Rannulf, the son of Hervey de Glanville (senior), was married to Bertha de Valoines, sister to Hervey Walter’s wife, Matilda/Maud de Valoines, daughters of Theobald de Valoines Lord of Parham in Suffolk, (variously spelt Valeines, Valoignes- not to be confused with Peter de Valognes sheriff of Essex, a Norman noble who became a great landowner of lands in six counties following the Conquest), making Rannulf de Glanville and Hervey Walter brothers-in-law. Hervey Walter’s son Theobald was obviously named after his maternal grandfather. And Hervey’s fourth son Hamo(n) was probably named after his wife Maud’s grandfather Hamo(n) de Valoines. Theobald de Valoines was the son of Hamo de Valoines who held Parham and several other lands in Suffolk and Norfolk from Count Alan of Brittany, in the Domesday Book. Theobald de Valoines and his brother Robert filius Hamo paid fines for a breach of the peace, listed in the Pipe Roll of Henry I (1130). The extended de Glanville, de Valoines and Walter families held a close familial relationship as evidenced by their appearance as witnesses to each other’s foundation and donation charters to various monastic orders.

As mentioned, Theobald Walter and his brother Hubert Walter, sons of Hervey Walter, were brought up in the de Glanville household where they were given their education. Hubert as dean of York, in his foundation charter to the Abbey of West Dereham in 1188, dedicated it for the salvation of the souls of his family and ‘my lord Ranulf de Glanville and Bertha his wife who nourished us’.

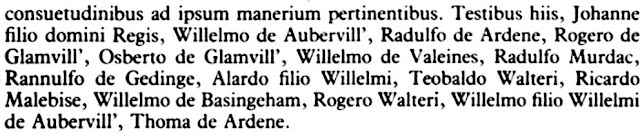

In a second charter, Hubert as Bishop of Salisbury circa late 1189 to early 1190, assigned the revenues from the chapel of St Laurence, Reading, to the hospital there for the support of thirteen poor persons. In this charter he makes a dedication: ‘for the souls of our ancestors and our successors as well, and for the souls of lord Rannulf de Glanville and lady Berthe his wife who educated us’. Witnesses included Theobald Walter and Bartholomew his brother (‘Teodeb[aldo] Gauteri et Bartholomeo fratre eius’). (University of Toronto- Deeds: Documents of Early English data Set, Charter document-0010020- http://deeds.library.utoronto.ca/charters/00100203 -Reading Abbey Cartularies, ed B.R. Kemp Camden Fourth Series, V.31,33, Offices of Royal Historical Society, London 1986-87)

It is possible that the

youngest son of Hervey Walter, named Bartholomew, may have been named after the

eldest son and heir of William de Glanville (elder brother of Hervey de

Glanville). Similarly, third son Roger Walter may have been named after William

and Hervey’s younger brother Roger de Glanville.

Unfortunately, Hubert’s dedications do not clarify whether his father Hervey Walter and Rannulf were brothers or just brothers-in-law. But the specific dedications do emphasise the closeness of their family relationship.

Theobald Walter’s Charter to Cockersand Abbey in Lancaster in 1194-99, described Ranulf de Glanville as ‘our dear Ranulf’, which again is ambiguous about their relationship.

Grant in frankalmoign by Theobald Walter for the health of the souls of King Henry II, King Richard, his son John, count of Mortain, our dear Ranulf de Glanville (‘Rannulfi de Glanvilla cari nostri’), Hubert Archbishop of Canterbury our brother, Hervey Walter my father, Maud de ‘Wal’ my mother. (‘The Chartulary of Cockersand Abbey’, vol. II, Transc. & Ed. By William Farrer, 1898, pp.375-376)

Similarly in another of Theobald’s charters, a benefaction to Furness Abbey in Lancashire made in Richard’s time, after acknowledging the health of the souls of Henry King of England, and King Richard his son and John Count of Mortain, he also grants “for the soul of Hubert, Archbishop of Canterbury my brother, and for the soul of my dear Rannulf de Glanville, and the soul of Hervey Walter my father, and for the soul of Matildis de Valoines my mother, and for the soul of my wife Matildis and our friends and ancestors and my successors”, etc.

‘..et pro anima domini mei H. regis Anglie, et Ricardi regis filii ejus, et pro salute domini mei Johannis comitis Moreton et domini Hibernie, et pro salute H.fratris mei Cantuar' archiepiscopi, et pro anima cari mei Ranulphi de Glanville, et pro anima Hervei Walter patris mei, et pro anima Matildis de Valoines matris mee, et pro salute anime mee, et pro salute Matildis sponse mee,..' .(Thomas Carte, The Life of James Duke of Ormond, 1851, v.1, p.xlii)

The de Glanville, the de Valoine, and it would appear the Walter families all originated in County Suffolk, and held ancestral lands in that county dating back to the Domesday survey.

In the ‘Chronicle of Jocelyn of Brakelond’ (a monk at the abbey of Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk in the mid to late 1100’s- p.122), Jocelyn recounts a dispute between the abbot of St Edmund’s and Hubert Walter Archbishop of Canterbury in 1198: ‘However, these and other altercations being brought to a close, the legate (Hubert) began to flush in the face, upon the abbot lowering his tone and beseeching him that he would deal more gently with the church of St Edmund, by reason of his native soil, for he was native born of St Edmund, and had been his fosterling. And, indeed, he had reason to blush, because he had so unadvisedly outpoured the venom which he had bred within him’, which appears to indicate that Hubert was born in County Suffolk and that it was his family’s native county. (Hubert was papal legate in England 1195 until 1198)

Theobald Walter held a large estate in Suffolk and Norfolk- in the sheriff’s returns in the Pipe Roll, 1 John (1200) for Norfolk & Suffolk, he is mentioned ‘in capite’ (ie. tenant-in-chief, held directly from the Crown) in the following entry, ‘Theobaldus Walterus reddit compotum de lxxvil. et xiiis. et iiiid.’ (£76.13s.4d.)

As a comparison, Theobald Walter’s grant confirmation of 1194 from Richard I of the whole of Amounderness in Lancashire, was held by the service of three Knight’s fees which were included in the scutage of £73.6s.8d of Knights of the Honour of Lancashire in 1189-1190. (Letters from Theobald Blake Butler to Lord Dunboyne, Butler Society, p.74 - ref. Carte’s Introduction to Life of Ormond, p.xlviii)

The lands held by families are the core of all research on the ancestral

origins of these families.

Herveius filius Herveii

Much speculation has resulted from the following entry, ‘Herveius filius Herveii’, and his relationship with Hamon Peche (Hamone peccatum), in the 1130/31 Pipe Roll for King Henry I, in the county of Suffolk:

‘The Great Roll of the Pipe for the 31st Year of the Reign of King Henry I’, New Edition with translation by Judith A. Green, Pipe Roll Society, London 2012, p.77-78:

SUFFOLK- New Pleas and New Agreements:

Translation in the same book by the editor, (p.78):

Suffolk- New Pleas and New Arrangements

Hervey son of Hervey renders account of 10 silver

marks for his land of Hamo Peche.

In the treasury 40s. And he owes 7 silver marks.

As there were few named Hervey documented as living in Suffolk in 1130,

it has been variously attributed to:

a) 1.Hervey Walter son of Hervey

b) 2.Hervey de Glanville (senior) and his son Hervey de

Glanville (junior)

c) 3.An undocumented son of Hervey de Bourges (due to the

reference in the suit to Hervey’s grandson Hamon Pecche by Hervey de Bourges’s

daughter Isilia, and land held by the Pecche family inherited from Isilia’s

father - Hervey de Bourges/Bituricensis held a substantial number of lands in

Suffolk in the Domesday survey as tenant-in-chief)

d) 4.A fourth possibility suggested by a couple of researchers: Hervey (Walter) son of Hervey de Glanville (senior)

Thomas

Carte, in his Introduction to his ‘The Life of the Duke of Ormond’,

(1851, p.xxxix) also stated:

‘In the Pipe Roll commonly called 5 Stephen (1139-40) but certainly some years older, is this entry: ‘Herveus filius Hervei reddit compotum de decem marcis, ut haberet socum et sacum, in terra sua’.

Literal

translation: Hervey son of Hervey is liable for ten marks in order to

have soke and sake of his own land. (sake and soke- a lord’s

jurisdictional right over the district attached to a manor with the right to

receive fines and other dues; this included the exclusive right over the

district to mill corn the mill being built and held by the lord as a means of

extra income.)

Theobald

Blake Butler in the ‘Letters from Theobald Blake Butler to Lord [Patrick] Dunboyne

(released by the Butler Society and John Lord Dunboyne, p.81), also discusses

Carte’s claim on this Pipe Roll entry:

‘In

the oldest Pipe Roll, in the Sheriff’s return for Norfolk and Suffolk is the

following entry: “Hervey fitzHervey paid £20 fine for erecting his lands

into manors” (Carte v.1 Intro xxxiv). Note Mr Hunter* considers the date of this Pipe Roll to be 31st

Henry I (1130-31). This entry appears in the same Pipe Roll as that

concerning Hervey fitzHervey and Hamon Peche.’

However,

on consulting this Pipe Roll of Henry I (1130), old and new editions, there

is no evidence of a second entry as described by Carte and Blake Butler.

Joseph Hunter (*referred to above), in 1833, published the Pipe Roll originally attributed to King Stephen (1135-54), which Hunter, in his ‘Introduction’, deduces is actually that of Henry I (1130): ‘Magnum Rotulum Scaccarii, vel Magnum Rotulum Pipe de Anno Tricesimo- Primo Regni Henrici Primi (1130-31) Quem Plurimi Hactenus Laudarunt Pro Rotulo Quinti Anni Stephani Regis’, and again, in that early publication of Hunter’s, only the one reference to ‘Herveus filius Herve’ is found, so it is difficult pinpointing where Carte found this particular reference, although the wording appears to be genuine and similar to other entries in the rolls- in particular, it exactly matches the entry preceding Hervey’s (viz. ‘Avenel renders account of 10 silver marks that he might have soke and sake in his land’- ’Avenellus reddit compotum de x. m. argenti ut haberet Socam et Sacum in terra sua’), so the two entries may have been confused in transcription.

The

‘Pipe Roll for 5 Stephen’ referred to by Carte, was firstly published in

the 17th century by Sir Simond’s d’Ewes who favoured a date for the

document of the fifth year of Stephen’s reign, but Joseph Hunter made a

compelling argument for dating this document to the fiscal year ending

Michaelmas 1130, and published the Roll in 1833. The Pipe Roll Society

subsequently reprinted Hunter’s Roll in 1929, providing a translation into

modern English, republished in 2012. The Introduction (p.ix) explains: ‘The

audit took place after Michaelmas, and we can see how the scribe occasionally

incorporated information which had come to his attention.’ This probably

refers to entries under the heading ‘New Pleas and New Arrangements’, such

as ‘Hervey filius Hervey’s’ entry, which could date it to 1131, or later.

One could argue that this Pipe Roll entry of 1130/31 could possibly relate to Hervey de Glanville and his son Hervey, as well as to Hervey Walter and his father Hervey, which needs to be kept in mind as we explore further evidence.

The theory of the de Glanville- Walter family biological link

There have been suggestions in some websites, based on a genealogical reference book written in 1882 on the de Glanville family, ‘Records of the Anglo-Norman House of Glanville’**, by William U.S. Glanville-Richards, that Hervey, father of Hervey Walter, was Hervey de Glanville of County Suffolk, father of Rannulf de Glanville who was such an important influence on the elevation of this family.

(** It should be noted that, although

Glanville-Richard’s research of this family has been thorough and detailed,

much of the speculative genealogical links, particularly the family trees, and

claimed ancestral origins and descents are incorrect, unsubstantiated, or very

questionable, but the number of de Glanville family members researched and the

referenced records quoted by Glanville-Richards are useful in trying to

establish fact from conjecture.)

Glanville Richards refers to an earlier publication, ‘The Norman People: and their Existing Descendants in the British Dominions and the United States of America’ (London 1874) by an anonymous author, which appears to be the first genealogical publication to canvas the idea of a biological link between the Butlers/Walters and the de Glanvilles, but again, much of the information presented and the author’s conclusions are questionable and speculative, with no evidence referenced for the direct biological link with the de Glanvilles.

The anonymous author claimed that “Hervey Walter’s grandfather, Walter (‘de Glanville’) appears 1086 as owner of estates in Leyland, Lancashire (Domesday)”. The actual Domesday entry for Leyland has land held by ‘Gerard, Robert, Ranulph, Roger and Walter’. There is no reference to a ‘de Glanville’ holding this land, and the author’s suggestion is purely conjectural. However, it should also be noted incidentally that those named in Leyland held the same names found in the de Glanville family in the following generations which may have been the basis of his unsubstantiated conclusions.

The author of ‘Norman People’ also makes statements such as: ‘Hervey Walter is a witness as Hervey de Glanville, to Rannulf’s foundation charter to Butley Priory’; and, ‘Hervey Walter or de Glanville had relinquished his barony of Amounderness to his son Theobald before 1165; at which time, as Hervey de Glanville, he held one fee in Suffolk from the See of Ely.’

These

claims will be further analyzed in detail later.

The de Glanville family timeline

The following is a timeline and brief summary of the charters and references found on the de Glanville family. Each will then be explored in detail.

|

Chart of |

De Glanville Family references

|

|

|

Year |

Ref-charter |

Details |

|

1066 |

Battle of Hastings- Roll of Battle Abbey-

‘John Foxe’s Copy’ |

Sire de Glanville, one of ‘Commanders

of the Archers du Val de Real and Bretheul and other places’ |

|

c.1066 |

Gallia Christiana, xi, 60 |

Rainald de Glanville witnessed a charter

in favour of Roger de Mowbray, also a commander of the archers |

|

1086

|

Domesday Book |

Robert de Glanville held 19 lands from

Robert Malet (18 in Suffolk, 1 in Norfolk) |

|

c.1103-05 |

Foundation charter to Eye Priory in

Suffolk by Robert Malet |

Donation by Randulph de Glanville; charter

witnessed by Hervey de Glanville (b.c.1080-82) |

|

c.1113 |

Foundation charter to Bromholme Priory on

edge of village of Bacton, Norfolk by William de Glanville |

William de Glanville born c.1080, elder

brother of Hervey de Glanville

|

|

c.1113 |

Act by King Henry I in favour of William

de Glanville |

Commanded that William shall have his

sake and soke and warren of his manor of Bacton, Norfolk, and forbade that

anyone shall cause him injury in this matter upon ‘my forfeit’ |

|

c.1131 |

Act by Henry I, re mother of William de

Glanville |

King granted as an inheritance to William

de Glanville, ‘his serjeant’, the office and land which belonged to his maternal

uncle William de Salt les Dames, to be held with sac and soc, toll and team

etc |

|

c.1127-1134 |

William de Glanville |

Witnessed a deed of Abbot William of St

Benet of Hulme, Norfolk. William inherited Robert de Glanville’s land of

Honing held from St Benet’s of Hulme |

|

c.1130 |

William de Glanville’s charter to

Sainte-Trinite of Tiron in Normandy |

Charter named his wife, Basilia, and two

sons Bartholomew and Anselm |

|

c.1134 |

De Contemptu Mundi, written c.1135-38 by Henry archdeacon of Huntingdon |

Rollcall of ‘powerful men now dead’-

“William de Glanville my kinsman; his son Bartholomew has succeeded to his

place”. Bartholomew de Glanville on Abbey of St

Benet Hulme’s list of knights 1134-1149 |

|

c.1125-1135 |

Roger de Glanville 2nd witness

to charter in Eye Priory Cartulary |

Eye Cart. No 346- Charter of Fulcher of

Playford to monks of Eye |

|

1130-31 |

Pipe Roll, 31 Henry I, p.77-78 |

Herveius filius Hervei renders account

for his land of Hamo Peche |

|

Pre 1135 |

Grant by Stephen Count of Mortain to

Ernald Russo for land in Stradbroke, Suffolk |

Witnessed by Hervey de Glanville |

|

c.1136-47 |

King Stephen confirmation charter to

Blythburgh Priory |

Witnessed by Hervey de Glanville |

|

1137 |

King Stephen’s confirmation charter to

Eye Priory |

Witnessed by Hervey de Glanville |

|

c.1146-50 |

King Stephen’s mandate to Hugh abbot of

St Benet of Holme |

Stephen ordered Abbot Hugh to allow

Bartholomew de Glanville the liberties in his manor of Bacton in Norfolk as

granted by King Henry to William his father |

|

c.1140’s |

Manor of Thorpe Murieux Suffolk granted

to Hervey de Glanville by Richard Bussell, Baron of Penwortham (Lancaster) for

his homage and service |

Hervey de Glanville granted it to

daughter Gutha as marriage dower |

|

c.1144-1154 |

Writ of Bishop Nigel of Ely |

Addressed to ‘H. de Glanville and R.

his son’ referring to a fee they hold of him, instructing Hervey and

Rannulf to ‘restore to the monks of Ely Cathedral, lands they were

possessing at Bawdsey, exempt from ties, and in a peaceful state’ |

|

c.1147 |

Castle Acre Priory- charter by Hervey de

Glanville |

Hervey donates rent from a house at

Bawdsey to Castle Acre Priory Witnesses: Mabilia wife of Hervey de

Glanville; Gorelmus; Osbert cleric; Osbert the priest |

|

c.1147 |

Castle Acre Priory- charter by Roger the

Priest of Bawdsey

(Witness Ordingus Gorelmus- ref: ‘First

Charter to St Edmund’s Bury, Suffolk’, in The American Historical Review,

July 1897, v.2. No. 4, p.688 [JSTOR]) |

Roger

donates rents to Hervey de Glanville snr and his chosen heir, with agreement

of Roger’s son Osbert (the cleric) Witnesses: Roger de Glanville.; Hubert

his nephew; Alexander nephew to the same; Osbert the priest of Benhall (de

Glanville property); Gorelmus (viz. ‘Ordingus Gorelmus’, 8th

Abbott of St Edmunds in 1148-57- tutored King Stephen as a child) |

|

1147 |

Crusade to liberate Lisbon from the Moors |

Contingent from Norfolk and Suffolk led

by Hervey de Glanville snr; letter written by priest named ‘R’ (Roger of

Bawdsey?) to Osbert of Bawdsey (his son) recounting events |

|

c.1150 |

Confirmation charter to Bromholme Priory

by Bartholomew de Glanville (Crawford Coll.; St Benet of Holme Register;

Monasticon Ang. v, 63) |

Witnesses: Hervey de Glanville and Ranulf

his son; Roger de Glanville (and Robert his son?); William de Glanville;

Osbert de Glanville, Reginald de Glanville. (NB. in Monasticon Anglicanum, same

witnesses with exclusion of “Robert his son”) |

|

c.1150-52 |

Shire Moot for Suffolk |

Hervey de Glanville snr gives speech

revealing age of 70+; witnessed by Hervei filius Hervei and

Robert de Glanville |

|

c.1154 |

Foundation Charter of Snape Priory by

William Martel (steward to K. Stephen) and family |

Witnessed by Hervey de Glanville and

Rannulf his son |

|

1156-58 |

Confirmation charter by William Count of

Boulogne and Mortain, son of King Stephen to the monks of Eye Priory (Eye

Priory cartulary) |

Witnessed by Rannulf de Glanville,

indicating his father Hervey de Glanville was now deceased |

|

c.1160-70’s |

Castle Acre Priory- charter by Roger de

Glanville

|

Roger donates his Earsham tithes

(Norfolk) Witnesses: “Hervey de Glanville,

William son of Flandina, Robert de Glanville my brothers” |

|

1163 |

Pipe Roll 8 Henry II |

Rannulf de Glanville replaced Bertram de

Bulmer as sheriff of Yorkshire |

|

c.1164 |

Yorkshire charter by Bertram de Bulmer

(EYC, I, 252) |

Witnesses: Rannulf de Glanville sheriff

of Yorkshire; Hervey de Glanville (Jnr) |

|

1165- 1169 |

Pipe Rolls, Henry II |

Bartholomew de Glanville and Robert de

Valoines overseeing building works of Orford Castle in Suffolk; Custodian

until his death in 1179; debts inherited by son Stephen de Glanville, and

then by son William de Glanville in 1190 clearing his debts in 1203. |

|

Red

Book of the Exchequer- Cartae Baronum (A.D.1166) |

Owing

knight’s fees: Hervey

de Glanville (Jnr)- 1 knts fee to Bishop of Ely for land in Suffolk Robert

de Glanville 3 ½ fees to Hugh Bigod, Norfolk Rannulf

de Glanville 1 ½ fees to Hugh Bigod; Roger

de Glanville 1 fee to Hugh Bigod & 3 fees in Essex in right of his 1st

wife Christine William

de Glanville 9 ½ fees to Honour of Eye Bartholomew

de Glanville 3 parts of a fee for village of Honing in Norfolk Theobald

Walter 1 fee for Amounderness |

|

|

Henry II |

Pipe Rolls- (first appearance in Rolls) |

1162- Rannulf de Glanville 1164- Hervey de Glanville (Jnr)- only

appearance 1165- Bartholomew de Glanville 1175- Roger de Glanville |

|

c.1171 |

Coxford/Broomsthorpe Priory Charter by Roger de Glanville (after the

death of Prior Mathew Cheney) |

Agreement about the use of a fishery at

Roughton (near Bromholme) confirming an existing agreement made with “Roger’s

father (?) Robert de Glanville in the time of Prior Matthew”, confirmed

by Hervey de Glanville (jnr)” |

|

c.1178 |

Marriage of Roger de Glanville |

Roger

de Glanville married 2ndly Countess Gundred widow of Hugh Bigod Earl of

Norfolk/Suffolk (d.1177) |

|

1174 |

Rannulf de Glanville |

Rannulf captures William the Lion, King

of the Scots Probably accompanied by nephew Theobald

Walter |

|

1170’s |

Charter to Rievaulx Abbey Yorkshire |

Witnessed by Rannulf de Glanville sheriff

of Yorkshire and ‘Osbert de Glanville his brother’; and a second charter witnessed by

Rannulf, Osbert and Gerard de Glanville (his brother) |

|

c.1171 |

Butley Priory foundation Charter by

Rannulf de Glanville |

Witnesses: Osbert cleric of Bawdsey,

Ranulf of Bawdsey, Osbert de Glanville, Gerard de Glanville, Hervey de

Glanville, Robert de Valoines, Radulph de Valoines & Savari de Valoines

etc. |

|

c.1174 |

Butley Priory- donation charter by Hervey

Walter |

Witnesses: Stephen de Glanville, William

de Glanville, Peter Walter, William de Glanville cleric, Rannulf of Bawdsey,

and sons Hubert Walter and Roger and Hamon, William de Valoines, Theobald de

Valoines (II), Robert de Valoines etc. |

|

1176 to 1181 |

Pipe Rolls, Henry II |

Roger de Glanville overseeing the

building of the keep at Newcastle upon Tyne, Northumberland |

|

1180 |

Rannulf de Glanville |

Appointed King’s Chief Justiciar |

|

1177 and 1180’s |

William de Glanville (son of ?) |

Acting as one of King Henry II’s

justiciars |

|

1180’s-1194 |

Osbert de Glanville |

Acting as one of the King’s justiciars |

|

1179-85 |

Confirmation charter by Rannulf de

Glanville, Yorkshire (EYC,1 256) |

Witnesses: Osbert de Glanville, William

de Auberville (son-in-law), Gerard de Glanville, Hubert Walter, William

filius Hervey, Also, Theobald de Valoines, Stephen de

Glanville, John de Glanville |

|

Grant

by Henry II to the nuns of St Mary’s, Wikes of lands of Crokesdlande (Nat.

Arch. E 40/5268) |

Witnessed

by Rannulf de Glanville, Hugh de Cressy, Hubert Walter, Bartholomew and Roger

de Glanville and Richard de Hastings |

|

|

c.1180’s-early 90’s |

Charter of John de Birkine, Joan

(Lenveise) his wife, Dionisia (Lenveise) wife of William de Glanville

(possible son of Rannulf de Glanville) |

John de Birkin b.c.1170 s.&h. of Adam

de Birkin, hereditary sheriffs of Sherwood Forest (family tree in EYC, iii, 358) William de Glanville (born c.1140s-50)

and Roger Walter donated their farm to nuns of Watton in Yorkshire;

William died before 1190 (possibly in 1185 Ireland), widow Dionisia remarried

Hubert de Anstey. 1180-86- grant by Wm Fossard to nuns of

Watton of land called Ghille’s land- witnesses: Rannulf de Glanville, Osbert

de Glanville, Hubert Walter John de Birkin possible cousin to Matilda

le Vavasour wife of Theobald Walter |

|

1185-89 |

Roger de Glanville |

Sheriff of Northumberland |

|

c.1186-89 |

Foundation charter to Leiston Abbey by

Rannulf de Glanville |

Confirmed by Roger de Glanville, Osbert

and Gerard de Glanville, Hubert Walter Witnesses: Roger de Glanville, Osbert de

Glanville, Theobald Walter and Roger Walter |

|

c.1186-89 |

Charter to Leiston Abbey- by Roger de

Glanville Donating church of Middleton |

For the souls of family including

deceased wife, parents and ‘Hervey de Glanville my brother’ Confirmation by Robert de Creke and Agnes

his wife of donation of Middleton Church by Roger de Glanville c. 1190-1221. |

|

1189 |

Death of King Henry II at Chinon |

Rannulf de Glanville and Theobald Walter

at death bed of King Henry II – witnessed Henry’s charter to Coverham Priory

the day before his death at Chinon |

|

3 Sept 1189 |

Coronation of Richard I |

Attended by Rannulf de Glanville, Gerard

de Glanville ‘his brother’, and Hubert Walter as Bishop of Salisbury (Chronicle of Reigns of Henry II and

Richard I, by Benedict of Peterborough, ed. Wm Stubbs, v.II, 1867, p.80-

list of barons present |

|

1190 |

Rannulf de Glanville died at Acre on

Crusade |

Died of sickness |

|

1192 |

Roger de Glanville on Crusade |

Conducted a daring reconnaissance before

the gates of Jerusalem, taking some Sarazens prisoner |

|

1193-95 |

Roger de Glanville |

Died in the Holy Land |

|

1193 |

Hubert Walter returns from Crusade and

visiting King Richard in captivity |

King Richard orders that Hubert Walter be

elected Archbishop of Canterbury and appointed Chief Justiciar |

|

1195 |

Feet of Fines Co Norfolk (Re Roger de Glanville’s land at Roughton

Norfolk) |

Agnes d/o William de Glanville, and 1st

husband Thomas Bigod sue Robert de Glanville over land in Roughton- payment

of 5 marks of silver- the defendant, Robert vouches to warranty Agnes,

Thomas’ wife, whose inheritance that land is. |

|

1200 |

‘The Countess Gundred’s Lands’, and Feet

of Fines for Norfolk and Suffolk |

Roger de Glanville’s widow Countess

Gundred begins actions for her ‘reasonable dower which falls to her ‘ex dono’

Roger de G., formerly her husband’. Claim against Robert de Creke and Agnes

his wife- she claims dower from lands situated in Middleton, Yoxford and

Roughton. Agnes is her uncle Roger de Glanville’s heir. In a separate claim in 1209 re Geoffrey

de Lodnes and wife Alice dau. of Hervey de Glanville, defendant asserts that

Agnes wife of Robert de Creke was dau.

and heir of William de Glanville. |

|

1203 |

Feet of Fines for Norfolk & Suffolk (Re Roger de Glanville’s land at

Middleton & Yoxford, Suffolk) |

Robert de Glanville claims against Robert

de Creke and Agnes his wife, tenants of Robert over 1 knts fee in Middleton,

and Yoxford in Suffolk under recognition of ‘morte d’ancestor’ with Robert

and Agnes paying Robert 20 silver marks to quit claim |

|

1209 |

Feet of Fines Norfolk & Suffolk (Re Roger de Glanville’s land at

Roughton, Norfolk) |

Robert de Glanville claimed under

recognition of ‘morte d’antecessors’ to land at Roughton, against William of

Edgefield who called Earl Roger Bigod (son of Countess Gundred and Hugh Bigod)

to warrant. Robert quit claims to the Earl who pays 40 marks of silver |

|

1200’s |

Priory of St Osithe de Chich in Essex, by

Bartholomew son of Robert de Creke and Agnes |

Dedicated to the ‘soul of Hervey de

Glanville, his mother’s (viz. Agnes’) grandfather’ (viz. Agnes d/o William de Glanville, son

of Hervey de Glanville) |

|

Early 1200’s |

Charter to Leiston Abbey by William son

of Alan (No.102) |

Witnessed by William de Glanville and

Walter his son (descendants of Adam de Glanville, desc of William de

Glanville the elder) |

|

Early 14th century |

Rent Roll of Butley Priory |

Rent Roll acknowledges Rannulf de

Glanville, his brother Hervey de Glanville, his sister Gutha de Glanville,

and two brothers Roger de Glanville and Osbert de Glanville, in 3 charters of

Leiston |

THE DE GLANVILLE ANCESTRY:

Glanville is in the district of Pont-l'Évêque

in the Calvados department of Normandy, between Le Havre and Caen,

which would explain the close association between the de Glanvilles

and the Malets (of Graville Sainte Honorine in Le Havre) and the de

Caens, and Hubert de Montecanisy of Deauville, and William (de

Beaufour) Bishop of Thetford, as shown in the Domesday Book.

see towns marked * on the map of Normandy

It would appear the first of the de Glanville family to arrive in

England was named Rainald de Glanville.

Mid-11th century records name a Rainald de Glanville, and

‘Le Sire de Glanville, and it is unknown whether they were

one and the same. There is also evidence of a William de Glanville, Dean and

Archdeacon of Liseaux, Normandy 1077 (Histoire Littéraire de la France).

‘Le Sire de Glanville’ was one of the’ Commanders of the Archers du Val de Real and Bretheul’ at the Battle of Hastings, who was listed in the Roll of Battle Abbey, in John Foxe’s ‘Book of Martyrs’ (also known as ‘The Actes and Monuments’ published in 1563).

The Roll of Battle Abbey; John Foxe’s Copy (‘English Surnames: An Essay on Family Nomenclature, etc’ by Mark Antony Lower, Vol.II, London, 1849: p.185):

Rainald de Glanville, about 1066, witnessed a charter in favour of Roger de Mowbray (Gallia Christiana, xi, 60):

The charter entry translates:

Roger de Molbray gave St Trinitatis land that he had in Grainville, for

his daughter, a nun there.

Witnesses Drogo of St Vigore and Rainaldus de Glanville.

As this charter was dated 1066, the year of the Conquest, it is likely that the witness ‘Rainaldus de Glanville’ is the same ‘Sire de Glanville’ at the Conquest (as is ‘Sire de Mombray’ viz. Roger de Molbray/Mowbray, in the same list by Foxe).

De Glanville in the Domesday Book

A Robert de Glanville held eighteen lands in Suffolk and one in Norfolk in the Domesday survey of 1086, as an undertenant of tenant-in-chief Robert Malet.

Map of Robert de Glanville’s lands in Suffolk (marked red dot) (NB. plus one land in Norfolk, named Honing):

Domesday lands held by Robert de Glanville, sub-tenant of Robert Malet, in Suffolk:

Of these lands, several were inherited by William de Glanville

father of Bartholomew who confirmed the donation of tithes from Dallinghoo,

Hollesley, Honing, Horham, Burgh and Aldeton to Bromholme Priory.

A William de Glanville was listed as donating the church of Bredfield to

Butley Priory, in the 14th Century Butley Priory Rent Roll dating

back to the original donations in the 12th century.

William de Glanville was obviously the elder heir, and his descendants

became the senior line.

Hervey de Glanville, brother of William de Glanville, inherited Bawdsey and Great Glemham, and his son Rannulf de Glanville held Benhall (the tithes of which he granted to Butley Priory), although historian Vivien Browne in her Eye Priory Cartulary, Pt II (p.61), comments that a record of descent of the advowson of Butley priory states that the founder Rannulf de Glanville was given the manor of Benhall by Henry II (or was it just confirmed?), and that it passed on his death to the eldest of his daughters, Maud, who married William d’Auberville, and thence to their son Hugh. Notably, a charter to Castle Acre Priory dated c.1147 of Roger Priest of Bawdsey, of rents of his house given to Hervey de Glanville ‘My lord’, one of the witnesses was Osbert Priest of Benhall, indicating a family link before Rannulf was given the manor by Henry.

It should also be noted that Hervey Walter held the fee of Wingfield

(and ‘Sikebro’, possibly Stradbroke/Stetebroc) the tithes of

which he granted to Butley Priory.

Robert the crossbowman or ‘Rob arbat’ (Roberto Arbalistarius)

It would also appear that Robert de Glanville may also be listed in

Domesday as Robert the Crossbowman, which would make sense given that the Sire

de Glanville was a commander of the archers at the Conquest. Robert

de Glanville held 18 lands in Suffolk, yet only one in Norfolk, ie. Honing,

all held from Robert Malet. Honing was originally held by Eadric of Laxfield

who held from the Abbey of St Benet of Hulme, and Robert Malet then held it from the Abbey. Robert de Glanville's heir William de Glanville also held Honing from the Abbey of St Benet of Hulme.

The adjacent land to Honing, ie. Worstead, was held by Robert the Crossbowman from St Benet of Hulme who used it for victualling the monks. The coincidence of these two men named Robert holding adjacent lands in Norfolk from St Benet of Hulme is notable, especially given that Honing was the only manor held by de Glanville in Norfolk.

Map showing close proximity of Honing to Worstead in Norfolk:

On checking his Domesday entries, Robert the crossbowman held

‘Appethorp’ (unidentified) in the Hundred of Forehoe in Norfolk as

tenant-in-chief; as well as Worstead (Norfolk) from St Benets; and [Great &

Little] Finborough in Hundred of Stowmarket in Suffolk held from Roger

d’Auberville:

‘Domesday Book A Complete Translation’ (p.1301):

Encroachments on the King: Hundred of Stow- In [Great & Little]

Finborough 1 freeman over whom Roger [d’Auberville]’s predecessor had half

the commendation and Eustace the other half of the commendation. Afterwards the

Count of Mortain held him but Roger held him when he left the land and Robert

the crossbowman under him. Now Roger Bigod holds him in the king’s hand

until it be adjudged. He has 15 acres of land. Then half a plough, now none. It

is worth 3s.

(p.1271): In [Great & Little] Finborough, Leofsunu, a freeman under the commendation only of Guthmund, Hugh de Montfort’s predecessor, held 2 carucates of land. Now Roger d’Auberveille holds it… Then it was worth £4, afterwards £2, and now 60s. In the same manor 18 free men under commendation only to the same Leofsunu held 1 carucate of land in the soke of the king and the earl… Roger d’Auberville holds all of these freemen through exchange etc.

(also refer to ‘Domesday Book and the Law’, by Robin Fleming, Nos.

3209, 3041)

Finborough/Finburgh was land held by Rannulf de Glanville which he granted to his daughters Amabila and Helewise, along with Bawdsey (held by Robert de Glanville in Domesday). At first glance, it would seem to indicate that Finborough was ancestral land, like Bawdsey, although in this case, inherited from Robert the Crossbowman (held from Roger d’Auberville). However, the Domesday entry for Finsborough indicates that Robert held a freeman with only 15 acres, which would seem to be too unimportant to be inheritable. However, Robert may have acquired, or been granted the adjoining lands of 2 carucates held by Roger d’Auberville who held considerable lands in several counties.

There would also be a long association between the d’Auberville family

and the de Glanville family through a marriage of Rannulf’s eldest daughter

Maud to William the son and heir of William d’Auberville who also witnessed several

charters of Rannulf, but notably, Maud and her husband did not inherit Finburgh

from her father, so the land did not come to her from her husband’s Auberville

ancestors.

The land of Appethorpe in the Hundred of Forehoe in Norfolk (between Norwich and East Dereham) is not identified, but had a recorded population of 22.8 households in 1086 and is listed under two tenants-in-chief, Count Alan of Brittany (annual value 5s.), and Robert the Crossbowman (annual value 32s.).

The land of Appethorpe held by Robert the Crossbowman as tenant-in-chief:

In “Appethorpe”, Aelfhere, a freeman, held 1 carucate and 30 acres of

land TRE for a manor. Then there were 2 villans; now 4. And there are 15

sokemen. There have always been 3 ploughs. There is woodland for 15 pigs. And 4

acres of meadow. Now there are 6 pigs, 20 sheep, 20 goats. Then it was worth

20s; now 32s. And it is 4 furlongs in length and 2 in breadth. And it renders

5d. of the geld.

So, it was a substantial grant.

Alan of Brittany’s entry for lands in this area has:

FOREHOE HUNDRED

Costessey held by Gyrth TRE, 4 carucates of land. To this manor is one

berewick, Bawburgh of 2 carucates. In Honingham Thorpe there is 1 carucate, a

berewick of this manor, etc.

In Marlingford 16 acres of land. In ‘Tokethorp’, Musard holds 30 acres

[from Alan] which belong to the same manor etc

MIDFORD HUNDRED (to the west of Forehoe Hundred, between Honingham and

East Tuddenham)

‘In [East] Tuddenham there were 10 sokemen of Gyrth’s in Costessey TRE

with 42 acres of land and they are in the valuation of Costessey. In “Appetorp”

there is 1 sokeman of Gyrth’s with 30 acres of land. This is in the same

valuation.’

Presumably, Appethorpe and Appetorp refer to the same vill. (ref: Domesday Book: A Complete Translation, ed. Dr. A Williams, Prof. G.H. Martin, 1992, pp. 1078, 1176)

As to the location, the other lands held by Count Alan of Brittany in this same area of Forehoe indicates that ‘Appetorp’ was located between East Tuddenham and Costessey, most likely near Honingham.

In the same location, Honingham, Honingham Thorpe, Marlingford and

‘Toketorp’/Tochestorp belonging to the same manor as Marlingford, Easton,

Taverham, Bawburgh and Barford, were all held by Alan of Brittany. Notably, Robert

the bowman’s land of ‘Appethorpe’, which he held as tenant-in-chief, is listed

in Forehoe Hundred, not Midford Hundred, so the land of Appethorpe must have

straddled the two Hundreds between East Tuddenham and Honingham.

Bowthorpe was held by King William. Colton held by William of Warenne

(later held by Peter Walter through his wife’s marriage portion).

Colney partly held by ‘Walter’ from Godric the Steward (19 freemen and 2

small holders with 4 plough teams, valued at £2 p.a.)- also I freeman of

‘Toketorp’, value 5s., also held by ‘Walter’ from Godric.

Notably, there were only nine crossbowmen named in the Domesday Book. All held a considerable number of lands as tenants-in-chief, indicating high rank in the Norman social order. As this Robert only held one land as tenant-in-chief, it lends to the argument that he held more lands as Robert de Glanville. There are several examples of land holders recorded differently by different clerics (eg. Walter de Caen als. Walter fitzAubrey als. Walter).

If Robert de Glanville was also Robert the crossbowman, then that could provide a close link with Walter the crossbowman who held lands near and part of Eye, and was a donor and witness to Robert Malet’s charter to Eye; he was possibly the ‘Walter’ who held the lands of Wingfield, Stradbroke (also held by Robert de Glanville) and Weybread/Instead, later held by Hervey Walter- more detail on these landholders in the blog chapter on the Walters (Part 2).

However, this theory of the identity of Robert the Crossbowman remains speculation.

Robert de Glanville’s heirs

Determining the relationship between Robert de Glanville, and William and Hervey de Glanville, is difficult due to lack of records. Historian Richard Mortimer wrote: “The history of 12th century families is complex and obscure. Partly the problem is one of basic facts, or finding the evidence to establish relationships; the complexity stems from the double link of each generation, with the father’s family and with the mother’s, meaning that the outlines of the group are constantly changing. The difficulty arises in deciding which particular relationships mattered to the individuals concerned. Various attempts have been made to reconstruct the Glanville family. The senior branch, tenants of the honour of Eye, of the abbey of St Benet at Holme and of the Warenne fee in Norfolk and Suffolk, has been known for many years (ie. the descendants of William).” (Richard Mortimer, “The Family of Rannulf de Glanville” article- Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, Vol. LIV, No. 129, May 1981)

We know that Robert de Glanville must have been born pre-1065, probably in the 1040-50’s. His lands were inherited by the following de Glanvilles, but their relationship to Robert is uncertain.

William de Glanville made a charter to Bromholme Priory in Norfolk c.1113, died c.1135, and was the elder brother of Hervey. He also appeared to be favoured by Henry I (1100-1135). Inherited the bulk of Robert de Glanville's lands.

Hervey de Glanville witnessed Robert Malet’s Charter to Eye Priory in

Suffolk c.1103-05, and he himself declared in a speech in c.1150-53 that he was

at least 70 years of age, therefore born c.1080-1083. Inherited some of Robert's lands.

Roger de Glanville witnessed a document in the 1125-35 period and two

documents in the late 1140’s, and appears to have died shortly after. He

witnessed the confirmation charter of Fulcher son of Humphrey filius Robert (a

favoured sub-tenant of Robert Malet in Domesday) in 1125-35; he witnessed

William’s son Bartholomew de Glanville’s confirmation charter to Bromholme

Priory circa mid-1140’s to 1150, in which, one copy (The Crawford Collection)

named his son as Robert (not named in the Monasticon Anglocanum copy); and he

witnessed the charter of Roger the Priest of Bawdsey to Castle Acre Priory

c.1147 in which Roger the priest donated his house rents to Hervey de Glanville

to give to the Priory. In that witness list, ‘Hubert’ is named as Roger de

Glanville’s nephew. Nothing else is known about this Roger, and it is difficult

sorting his relationship to the later Roger de Glanville and distinguishing their respective

records.

Given the age disparity, it is probable that Robert de Glanville (of Domesday) was either the father, or an uncle, of William, Hervey and Roger.

Hervey de Glanville, in his speech in c.1150-53, also claimed that he ‘was

a very old man, having constantly attended the County and Hundred

Court for above fifty years with his father, before and after he was knighted’,

indicating that his father was alive ‘before and after he was knighted’ which

would have occurred c.1100-02, and therefore born c.1080-83.

Several historians claim that William and Hervey had other brothers

named Walter and Robert, but there is no clear evidence of their existence.

Robert Malet’s foundation charter to Eye Priory c.1103-05 names Rannulphus

de Glanvillis granting his tithe of Yaxley/Jakesleyam hospice in

Suffolk (notably Hubert de MonteCanisy also donated his hospice at Yaxley,

presumably the same hospice) and the charter was witnessed by Herveus de

Glanvill’, which would seem to confirm the close relationship between

Rannulph and Hervey and would explain Hervey’s son’s name of Rannulf. However, placing this Rannulphus in the family tree, and his relationship to Robert de Glanville, is difficult.

Rannulphus de Glanville did not hold any lands in Domesday (unless only

by the name of ‘Rannulphus’, of which name, 94 lands were held

throughout England). Whether this Rannulphus was also a son of Rainald de

Glanville, and a brother of Robert de Glanville, is unknown speculation. It is also possible that Rannulphus was the son and heir of Robert de Glanville, and Rannulphus' sons, William and Hervey, inherited in turn.

Notably, Rannulphus did not hold Yaxley in Domesday so he must have

acquired a stake in the ‘hospice’, post Domesday. Yaxley was partly held by Hubert

de MonteCanisy and Robert Malet’s mother from Robert Malet, and partly by William

Beaufour Bishop of Thetford (who died in 1091). The ancestral area of MonteCanisy

in Normandy was only about 10 kms north of the de Glanville ancestral lands in

Glanville (see map above), and also close to the Beaufour family lands, so

there would have been an historical ancestral connection between these

families.

The exact translation of the Eye charter donations:

Hubert de MonteCanisy gave to God and St Peter his land at Yaxley, his

lodging/hospice (‘hospitium’) since his tenure.

Ranulphus de Glanvillis offered on the altar of St Peter the lodging/hospice