THE WALTER FAMILY

NB. Clicking on an image will open a higher resolution image.

The surname of the Butlers of Ireland has its origins in the hereditary office of ‘Butler of Ireland’ originating with Theobald Walter, 1st Butler of Ireland.

The first misconception that needs clarification is the original surname of this family was WALTER, NOT FITZWALTER.

The

ancient Latin documents do not refer to any member of this family as

‘fitzWalter’ as has often been incorrectly used down through the centuries by

various historians.

Theobald

was always named as Theobald Walter/Theobaldus Walteri in official records,

not as Theobald fitzWalter. Similarly, his father was always named as

Hervey Walter, his brothers Hubert Walter, Roger Walter and Hamon Walter, and his

uncle Hubert Walter, and cousin Peter Walter.

The surname or family name of ‘Walter’ was most unusual for the late 11th and the 12th century as it was a hereditary name used by several generations of the Walter family. The rise of hereditary surnames was attributed to the creation of the Domesday Book in 1086, where, according to records, the Norman nobility and upper classes had to create surnames to identify and distinguish between people of the same names, to prove hereditary ownership of property assigned after the Conquest. The sources of surnames included patronymic, topographic origin, occupational, and in some cases, reflecting particular physical attributes such as complexion, hair colour, stature etc. and their resultant nicknames. Many of these family names were fluid and changed for those children not in a direct hereditary line. One would assume that ‘Walter’ originated as a patronymic name after the original Norman ancestor, however, unusually, the more common form would have been ‘filius Walteri’ which evolved into ‘fitzWalter’, but not in the case of this family in which, all members of the extended family used just the singular name ‘Walter’.

The timeless question of the ancestral origin of the patriarchal founder of the Irish Butler/Ormonde family, Theobald Walter and his father Hervey Walter, has inspired much research by world-renowned historians for many centuries, and, despite much speculation, the answer has never been discovered. In fact, it is most unlikely the unequivocal answer will ever be found.

The many genealogical statements found in various publications on the family and on the web, declaring a particular ancestral genealogical line or another for this family, are all unproven. The documentation required to make such statements either does not exist, or has not yet been found. The problem with the world wide web is that many of these incorrect statements are copied and perpetuated on other websites and become an established ‘truth’ by those who don’t check their sources or do the deep research required.

The purpose of this blog article is to present the documents that have been discovered, and hopefully inspire other researchers to look at the information and documentation available on the origins of this Irish Butler/Walter family, to form their own opinion and continue the search for possibly undiscovered ancient documents deeply hidden in various British national and church archives and even French archives, that may prove or disprove the many ancestral theories and help solve the mystery of the Butler’s/Walter’s 11th century ancestors and their place of origin.

Background information on the rise in status of this family- Hubert Walter, son of Hervey, and his rise to power, as recorded by contemporary chroniclers

Available Records of the 11th to 13th centuries

Chapter 2: The surname origins of the Walter family

Ancestral candidates named Walter in Co. Suffolk in Domesday:

A. Walter ‘who held of this manor’

Chapter 3: The theoretical origins of the Walter family in Normandy

Analysis of the various theories of the Norman origins of the Walter family:

1. The de Clares

Chapter 4: Lands held by the Walter family in the 12th century in England

Introduction

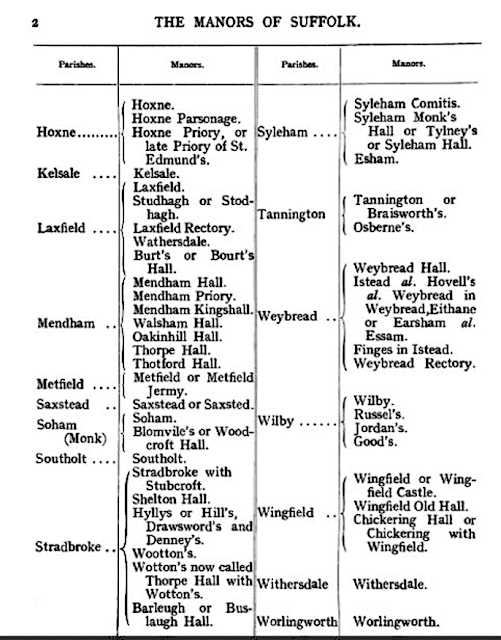

The lands of the Walter family in Suffolk

Theobald Walter’s Amounderness fee in Lancashire

CHAPTER

1

Theobald Walter’s title ‘Butler of Ireland’

Theobald Walter, patriarchal founder of the Butlers of Ireland, was granted the hereditary title of Butler of Ireland, or ‘Pincerna Hiberniae’, having served as butler to Prince John (b.c.1167) who was created Lord of Ireland in 1177 by his father, King Henry II. No records reveal the date Theobald was granted this hereditary title, but it probably evolved during the reign of King Richard I (1189-1199), as, before the middle of Richard’s reign, he was only referred to as ‘pincerna’ to Prince John- 'pincerna domini comitis Moretoniae in Hibernia', and he began to use the style 'Pincerna Hiberniae' by about 1196, probably after he confirmed his allegiance to King Richard following Prince John's rebellion in 1193-94.

Some historians have suggested that Theobald

was granted this title of ‘Chief Butler of Ireland’ at the time of Henry II’s

invasion of Ireland in 1171. Henry’s huge army of 500 knights and 4000

horsemen, foot soldiers and archers arrived in Waterford on 400 ships in

October of that year. The Irish historian, William H. Grattan Flood wrote an

article “Lismore Under the Early Anglo-Norman Regime”, published in the

Journal of the Waterford and South-East of Ireland Archaeological Society, Vol.

V, 1899 (Waterford City and County Council website), pp132-33, in which he

stated:

“Richard de Lacy was named Lord Marshal of

Ireland; Hugh de Lacy, Justiciary or Lord Constable; Bertram de Verdun, Chief

Seneschal; Theobald Walter, Chief Butler; and de Wellesley, Royal Standard

Bearer.”

Flood did not reference this statement, and

there does not appear to be a record of the list of the 500 knights who

accompanied Henry to Ireland, nor any historical document naming Theobald as

such in the 1171 invasion.

A book published in 1766, “The History and

Antiquities of the City of Dublin”, written by Walter Harris Esq., gives an

alphabetical list of “such English adventurers as arrived in Ireland during

the first 16 years from the invasion of the English” (ie. 1169-1185),

includes the names ‘Fitz-Walter (Theobald) and Glanville (Reginald de)’

(sic), referring, in this case, to 1185 when John, as Lord of Ireland, first arrived with his entourage including Rannulf de Glanville as Chief Justiciar and Theobald who was assigned as John's pincerna.

The Red Book of Ossory, fol. 90a, has a list

of the 34 knights who accompanied FitzStephen who landed at Bannow Wexford in

May 1169. This was soon followed by Strongbow’s invasion in 1170, a list of

knights listed in Camden (Brittania, 1610), most of whom were the names of the

knights who accompanied FitzStephen (not including Theobald Walter nor his uncle Rannulf de Glanville), but there is no subsequent list of those

who accompanied Henry in 1171, including an estimated 500 mounted knights and 4,000 men-at arms and archers.

Rannulf de Glanville was promoted to sheriff of York in 1163, and subsequently Sheriff of Warwickshire and Leicestershire, but in 1170, along with many of the high sheriffs, he was removed from office for corruption. This was around the time of the Irish invasion. It was not until 1173 that Rannulf was appointed Sheriff of Lancashire, and the following year as Sheriff of Westmoreland, and, after his capture of the King of Scotland in that year, his promotions continued, being reappointed Sheriff of York in 1175, and a justice of the king’s court and justice itinerant of the northern circuit in 1176. There is no doubt that Theobald would have been part of Rannulf’s household at this time, as was his brother Hubert.

Rannulf’s cousin Bartholomew de Glanville, head of the senior branch of the de Glanville family, is recorded as raising supplies to send to the army in Ireland:

‘The Calendar of Documents relating to Ireland’ (H.S. Sweetman [1875])- 1170-1171- Norfolk and Suffolk: Bartholomew de Glanville, Wimar the chaplain and William Bardul, render their account; for 320 hogs, sent to the army of Ireland, 26l.16s.5d; 15 days pay to 36 masters and 468 equippers, 33l.13s.; making bridges, hurdles, and other ships apparel, 6l.5s.5d; 6 handmills and their appendages, 14s.4d., by the King’s writ. (Pipe Roll, 17 Henry II,; Rot.1)

In 1171-72, No. 26, in the same document: “Lancaster: Roger de Herleberg renders his account; for £68 scutage of the honor of Lancaster for the army of Ireland; pardon by the King’s writ for Randulf de Glanville 20s; and he owes £16.”

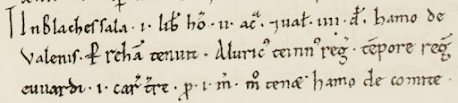

Theobald and his brother Hubert (both born circa mid-to-late 1130’s to early 1140's) were brought up in the household of their powerful uncle Rannulf de Glanville, King Henry II’s Chief Justiciar, referred to by Hubert in his Charter to West Dereham Abbey in which he stated “my lord Ranulf de Glanville and Bertha his wife who nourished us”. When Prince John was about 12 years of age, he was also placed in the household of Rannulf to be taught the business of government. Theobald and his uncle Rannulf de Glanville accompanied John on his first visit to Ireland in 1185 with 300 of his knights and administrators, and were well rewarded with lands. The cost of the freight for Theobald’s equipment was borne by the royal exchequer. Pipe Roll 31 Henry 11 p2:

“Et pro i. navi conducenda ad harnasium

Theobaldi Walteri lxvi s. et viii.d. per breveregis”

It was during this excursion that Theobald was first referred to as ‘pincerna’, in the records, although he may have acted in that role before that, probably appointed by John’s father Henry II at the instigation of Rannulf.

M.T. Flanagan in her entry on ‘Theobald Butler [Walter]’ in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, suggests that “Theobald may have been ‘pincerna’ of John’s personal household rather than the holder of an office with any specifically Irish connotations.” This possibly came about due to John’s placement in Ranulf de Glanville’s household. Flanagan then refers to two charters in Ireland to which Theobald was witness and named as ‘pincerna’.

‘The Calendar of Ormond Deeds 1172-1350 A.D.’ edited by Edmund Curtis (Irish Manuscripts Commission, Dublin 1932):

In Ormond Deed No.7, in Prince John’s charter (in part) to John’s chamberlain Alard fitzWilliam, Theobald, styled ‘pincerna’, witnesses along with the seneschal and dapifer, issued on the eve of John’s departure from Ireland, at Wexford in 1185 (also NL Ire., MSD.8).

This charter appears to have been the earliest reference to Theobald’s position as butler, and seems to be an isolated occurrence as Theobald is not referred to as ‘pincerna’ again until 1192, so may have been directly related to their visit to Ireland, probably appointed by john's father, Henry II.

Curiously, the offices of seneschal and dapifer were the same, ie. the steward (‘dapifer’ is Latin for ‘seneschal’) in charge of domestic arrangements, provisions and stores, and the administration of servants, so why John had two stewards is not explained, unless de Verdun was Henry’s appointed seneschal for the expedition to Ireland, and de Wenneval was John’s personal dapifer/steward.

Of the other witnesses, Bertram de Verdun,

seneschal, was a close confident of King Henry II and was appointed seneschal during

Henry’s earlier excursion in 1171 to clarify his position as Strongbow’s liege

lord. He was sheriff of Leicestershire and an itinerant justice, and was

dispatched to Ireland in 1185 to clear up the dangerous situation caused by John’s

diplomatic and military failures. Bertram de Verdun was grandfather to Rohese

de Verdun (dau. of Nicholas de Verdun) who was second wife to Theobald le

Boteler 2nd Chief Butler of Ireland.

William de Wennevall is listed as

John’s ‘dapifer’ in Ireland in this charter. Although the position of ‘dapifer’

is Latin for seneschal (held by Bertram de Verdun), this particular office seems

to imply that Wennevall was John’s ‘dapifer’ in his personal household.

Wennevall was appointed High Sheriff of

Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire during King Richard’s absence from England from

1190. As constable of Nottingham Castle, he held the castle for John during his

insurrection in 1193-94, when, in 1194, King Richard placed it under siege and

then made an assault on the castle. William de Wennevall surrendered the castle

and threw himself on the King’s mercy. Similarly, Theobald surrendered

Lancaster Castle when ordered by his brother Hubert, the archbishop of

Canterbury, and pledged his loyalty to Richard. There is speculation that the

character of the villainous sheriff of Nottingham in the legend of Robin Hood

was based on William. (als William de Wendeval, Wendenal)

William de Cahaines/Kahaines was appointed as

John’s personal seneschal after returning to England (see Dublin charter below).

Gilbert Pipard was sent to Ireland by

Henry II to govern Ireland together with John Cumin and Bertram de Verdun. He

was appointed High Sheriff of Lancaster Castle 1185-1189, but in consequence of

his official duties as Justice itinerant, put his brother Hugh in his place to

execute the office for him in 1185-86. In 1186-87, the office of Sheriff was

executed by Gilbert’s brother Peter, as his deputy (Lancashire Pipe Rolls, Wm

Farrer, pp.56,64).

These appointments by Henry II would suggest that many of John’s administrative officers who accompanied him to Ireland were selected by his father.

On Richard’s succession to the throne in July

1189, he granted his brother John the title of Count of Mortain.

John would establish his own ministry through which he could govern his Irish dominion, as well as his English possessions which Richard bestowed upon him. These would include Stephen Ridell as the first lord chancellor of Ireland appointed in 1186, William de Kahaignes as his seneschal replacing de Wenneval, and Theobald Walter would continue as his butler in Ireland.

M.T. Flannagan in her article on Theobald Walter in the Oxford DNB also wrote: ‘Theobald is next so described as ‘pincerna’ in John’s charter in favour of the city of Dublin 11 May 1192, witnessing alongside John’s chancellor and seneschal, suggesting that Theobald may have been pincerna of John’s personal household rather than holder of an office with any specifically Irish connotations.

This charter was translated in Curtis and McDowell’s

‘Irish Historical Documents’, in which they have translated the original

document as ‘Theobald Walter, my butler,’:

However, in a Latin version of the same

charter, published in the ‘Historic and Municipal Documents of Ireland A.D.

1172-1320’, although William de Kahaignes is described as ‘senescallo

meo’, and Stephen Ridell, ‘cancellario meo’, Theobald is just

described as ‘pincerna’ not ‘pincerna meo’.

Flannagan continued: ‘A charter of John

Cumin, archbishop of Dublin, in favour of Theobald refers to him as’ “Theobald,

pincerna domini comitis Moretoniae in Hibernia”/ ‘Butler of the count of

Mortain in Ireland’ (Curtis, Ormond Deeds, no. 11; Cott. MS fol.266)”,

indicating that the office was deemed to be attached to John’s lordship of

Ireland.’

The referenced Ormond Deed No.11 translates the record as: ‘John [Archbishop of Dublin] “minister of the Church of Dublin” grants to Theobald, Butler of the lord the Count of Mortain in Ireland, and his heirs, etc. Approx. date of deed 1193.’ This is much more specific in its description of Theobald as John’s butler in Ireland.

During the latter part of Richard’s

reign, probably after 1196, Theobald then adopted a fresh seal, adding to his

name the style ‘Pincerna Hiberniae’. By this time, John had been exiled

to the Continent for his 1193-94 rebellion against his brother Richard, and

Theobald had sworn his loyalty to Richard.

In his benefaction to Wotheny/Owney/Woney Abbey in Co Limerick in King Richard’s reign, Theobald began the charter: “Omnibus sanctae matris ecclesiae filiis tam presentibus quam futuris, Theobaldus Walterus pincerna Hibernie salutem.” (pincerna Hibernie= butler of Ireland).

Lancashire Pipe Rolls, p.340:

“Letter of Theobald Walter certifying that his charter of grant to the

monks of Wotheny, etc.

Editor notes: “The probability is that the colony of monks in

Wyresdale removed to Wotheny c.1198, or between 1195 and 1199.”

Theobald’s

charter refers to ‘Richard King of England’ and ‘John Count of Mortain’,

so must have been dated before John’s accession in 1199.

Monasticon Anglicanum, v.6. pt.2, p.1136-37:

Wotheny/Owney abbey was in the townland of

Abbington, near the modern village of Murroe. It is thought that Theobald was

probably buried at Wotheny Abbey.

(See Journal of the Butler Society, v.4,

no.3, p443- re Charles and Rosemary Butler’s donation of a Memorial to Theobald

Walter, commissioned to mark his burial place at the ruins of Wotheny Abbey)

Charter of Theobald Walter to

Furness Abbey- Richard I (Carte, p.xlii):

"Omnibus sanctae matris ecclesiae filiis tam presentibus quam futuris, Theobaldus Walterus pincerna Hybernie salutem. Sciatis me pro Dei amore et beate Domini genetricis Marie, et pro anima domini mei H. regis Anglie, et Ricardi regis filii ejus, et pro salute domini mei Johannis comitis Moreton et domini Hibernie, et pro salute H.fratris mei Cantuar' archiepiscopi, et pro anima cari mei Ranulphi de Glanville, et pro anima Hervei Walter patris mei, et pro anima Matildis de Valoines matris mee, et pro salute anime mee, et pro salute Matildis sponse mee, et pro salute animarum omnium amicorum et antecessorum et successorum meorum dedisse et concessisse, et hac presenti carta mea confirmasse in puram et perpetuam eleemosinam Deo et sancte Marie, et abbati, et monachis qui exierunt de Furneis in cantredo meo de Woednicachelan, et Woednisfergan totum thuedum de Woednifichwith in quo villa de Clonken sita est, cum tota medietate atque de Molcerne in quantum praedictus thuedus se extendit super praedictam aquam de Molcerne per omnes rationabiles divisas suas, cum omnibus pertinentiis suis, &c. Hiis testibus Philippo de Wirecestre, Hamone de Valoines, Gaufrido filio Roberti, Willelmo de Burgo, Ric’ Tirel, Ric’ de sancto Michaele, Moricio fil. Moricii, Tilleberto de Kentewell, Waltero de Kentewell, Adam de Rachlesden, Willelmo fil. Martini, Amaturi de Belfago, Jordano de Lusch’, Radulpho de Sancto Patricio, Thoma de Kentewell, Ricardo de Waleton, Willelmo de Blie, Jordano fil. Jordani, Ricardo Clerico, Ranulpho Clerico, Radulpho Clerico de Tyrmi, Johanne de Rupe, et multis aliis."

The seal affixed to this charter is of green wax, on which is impressed the figure of a cavalier on horseback, in the usual method, with this inscription, Sigillum Theobaldi Walteri.

This original charter, the seal of which deserves to be engraved, is to be found among the records of the duchy court of Lancaster, kept in Gray’s Inn, in the 55th box of deeds, according to Carte.

As in many other charters of Theobald, his witnesses included three de Kentewell brothers and Adam de Rattlesden, of Suffolk, who appear to be close friends of Theobald.

Similarly, Theobald founded a monastery at Arklow, a cell of Furness Abbey, dated after 1199, as he names King John ‘Johaniis regis Angliae’ in the charter. The wording is similar to his charter for Wotheny, except this time, he includes, “for the soul of William Marshall”.

It is interesting that Marshall has been

included in this list of Theobald’s family members, following his uncle Rannulf

and preceding his brother Hubert, probably because William Marshall was

Theobald’s overlord in Arklow which was part of his Lordship of Leinster.

Monasticon Anglicanum, v.6. pt.2, p.1128:

Translated in part: “and for the soul of

Ranulph de Glanville, and for the safety of the soul of count William Marshall,

and for the safety of the soul of Lord Hubert Canterbury Archbishop my brother,

and for the soul of Hervey Walter my father and Matilda de Valoines my mother,

and for the safety of the soul of Matilda my wife, etc.”

Notably, Theobald’s mother’s name is written as

‘Matildis de Valuniis, matris mee’ in this charter, and as ‘Matilda

de Waltenes matris mee’ in the Wotheny charter which the editor corrected

to ‘Valoniis’.

William Marshall, married Isabel de Clare, the daughter of Strongbow and heir to his lordship of Leinster. Richard de Clare (c.1130-1177) Earl of Pembroke and Strigul, later known as Strongbow, was a Norman lord from Wales who started the Norman conquest of Ireland, initially brought to Ireland in 1170 by Dermot MacMurrough King of Leinster who was in dispute with the High King of Ireland, Rory O’Connor who had deposed him, and, in return for his support, promised Strongbow vast lands, and marriage to his daughter and heir. In 1171, when Dermot died, Strongbow inherited the kingship of Leinster which he held until his death in 1177.

In 1189, the 42 year old William Marshall was

granted the hand and estates of the 17 year old heiress Isabel de Clare, and

through her, acquired large estates in England, Wales, Normandy and Ireland,

making him one of the richest men in the kingdom. Although he was the de facto

Earl of Pembroke though his marriage to Isabel, he was officially granted the

title in 1199.

Prince John disseized William of a portion of Leinster and handed it out among his friends and supporters. William Marshall appealed to King Richard who insisted upon John making restitution. John was compelled to yield, but not entirely, as he managed to secure ratification of a grant he had made to Theobald out of the Marshall’s lands. However, as a compromise, it was settled that Theobald should hold the estate as an under-tenant of William, not as tenant-in-chief of John. This is an example of John’s close relationship with Theobald at that time.

An article in Irish Historical Studies, recounts a translated conversation between King Richard and Prince John, quoting from the biographical verse in ‘L’Histoire de Guilluame le Marschal’ written by an unknown author self-named ‘Johans’, mid-13th century:

King Richard: “For my sake, you will come to an agreement with him [William Marshal]”

Prince John replied: “I gladly agree to this providing that the gift remain intact of lands I have made over to my men and confirmed…”

Richard: “What could he [William Marshal] possibly have left, since you [John] have given and surrendered all his land to your men”John “I crave your indulgence, since that is the way you [Richard] want it, to have him [Marshal] agree to let Theobald, my butler, keep the land I have invested him with”.

William lived an extraordinary life, beginning

as a knight errant of great skill and prowess, gaining fame and fortune competing in tournaments in France,

and becoming highly trusted by four kings from Henry II to Henry III, as well

as by Henry’s estranged wife Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine whom he helped escape

from an ambush in Aquitaine, resulting in his own capture and wounding. Eleanor

would pay his ransom, and he remained a member of her household for two years,

continuing to raise his reputation as a chivalrous knight, successfully taking

part in many tournaments. William served as Henry II’s eldest son and heir

Henry’s tutor-in-arms before his untimely death in 1183, after which William

undertook a mission to the Holy Land to place his lord Henry's cloak on the altar at the Holy Sepulchre, returning to re-join the court of Henry

II, serving as a loyal captain through Henry’s difficult last years. He is said

to have been the only man ever to unhorse Richard while covering Richard’s

father Henry II’s flight from Le Mans to Chinon in 1189 when Richard was allied

with Phillip II against his father, shortly before Henry’s death. Despite this,

Richard admired William’s legendary loyalty and military accomplishments which

he acknowledged were too valuable to dismiss, and when Richard went on Crusade

in 1190, William was appointed on the council of regency in his absence. Although

he held a fractious relationship with King John, he remained loyal to John

throughout the hostilities between John and his barons. It was William whom

John trusted on his deathbed to ensure John’s 9 year old son Henry would get

the throne. The king’s council named William to serve as protector of the 9

year old Henry III, and as regent of the kingdom. In 1216, during the First Barons' War over the succession, Prince Louis of France entered London and proclaimed himself 'King of England', supported by various English barons who had resisted the rule of King John. In May 1217, Prince Louis's army led by Thomas Count of Perche, had taken the city of Lincoln and held Lincoln Castle under siege. The 70 year old Marshall marched his forces and supporting barons to the city to break the siege and successfully routed Louis's army. Thomas Count of Perche fought to the death as the siege collapsed. Louis was forced to make peace on English terms and signed the Treaty of Lambeth in September 1217, agreeing he had never been the legitimate king of England.

In 1195, William Marshall commenced the

building of Kilkenny Castle to control a fording-point of the River Nore and

the junction of several routeways, completing it around 1210- nearly two

centuries later, it would become the seat of the Butlers.

William died in March 1219 and was invested

into the order of the Knights Templar and buried in Temple Church in London. Of

his five sons, none left issue, and William’s vast estates were divided between

his five daughter’s husbands, two of whom were ancestors to the Bruce and

Stewart kings of the Scots, and the last Plantagenet kings Edward IV through to

Richard III.

William’s son and heir, William Marshall II, was

overlord to Theobald II le Botiller who was closely linked by service to

William who was Lord of Leinster and Justiciar of Ireland, and from whom

Theobald continued to hold some of his estates.

William Marshall was replaced as justiciar by Geoffrey de Marisco who held Theobald II’s wardship and whose daughter Theobald married.

In Ormond Deed No.16, dated between 1195

and 1206, a charter between the Archbishop of Cashel and Theobald Walter, Butler

(Pincerna) of Ireland:

And a further charter in Ormond Deed No.22-

re Theobald Walter, Pincerna of Ireland who founded the Priory of St John the

Baptist of Nenagh c.1200:

see Latin charter for Nenagh in Monasticon Anglicanum,

v.6. pt.2, p.1145:

Carta Fundationis ejusdem, circa Annum Domini MCC.

Universis sancta matris ecclesie filiis, ad quos presens scriptum pervenerit, Theobaldus Walter pincerna Hibernie, salutem. Etc

Although this Ormond Deed does refer to an

earlier deed by Theobald Walter the first Pincerna dated A.D.1200, the list of

witnesses to this “Bond by the prior and canons”, indicate that this “bond”

was witnessed in the mid 1220’s, and several were closely associated with

Theobald II, including his sister Maud’s husband, and those associated with his

wardship after his father’s death.

Marian O’Brien was elected Archbishop of Cashel

in 1224; ‘R’ Bishop of Killaloe presumably Robert Travers elected in 1217 until

1221 and again in 1226. Gerald de Prendergast d.1251 married firstly Theobald

Walter’s daughter Maud Walter (b.c.1196-1205), and secondly married Maud de

Burgh in c.1240.

Peter de Birmingham, son of Sir William de

Birmingham who helped Strongbow invade Ireland. Peter was one of the barons in

arms to secure the Magna Carta. He was the first to hold the wardship of

Theobald le Boteler II, before it was granted to William de Braose and then

Geoffrey de Marisco; Maurice fitzGerald c.1184-1257, 2nd Lord of Offaly

married to Eve de Birmingham (m.2. Geoffrey de Marisco); Jordan de Marisco

b.c.1195 d 1234, son of William de Marisco (brother of Geoffrey) and Lucy de

Alneto (dau. of Alexander de Alneto d.1194); Adam de Alneto d.1244, son of

Alexander de Alneto.

There are several other grants involving Theobald as Pincerna Hibernie, in the Ormond Deeds.

One of interest, concerns Theobald being

excommunicated and brought to account by his brother Hubert, for overstepping

his powers:

Ormond Deed No 23:

Similarly, in early 1200, Theobald fell out of

favour with King John who deprived him of all his offices and lands because of

irregularities as Sheriff of Lancashire.

Complaints against Theobald, the first year of John’s reign:

Several

complaints by demesne tenants of Amounderness complaining of being dispossessed

of lands by Theobald are outlined in the Lancashire Pipe Rolls (pp.120, 123,

135, 136).

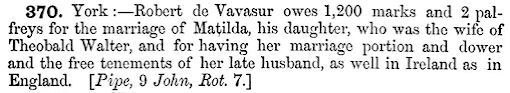

Roger de Heaton, to whom Theobald and his father Hervey had granted lands, was granted a confirmation charter by King John, dated March 1201, whereby ‘Roger paid 15 marks for seisin of the estate of Broune (now Bourne Hall, in Thornton, Lancashire), of which he had been dispossessed by Theobald Walter, who had taken his charter of this estate from him’.

In the autumn of 1199, several Lancastrian nobles proceeded overseas to King John and presented a series of criticisms of Theobald’s period as sheriff. It was claimed that knights, thegns and freemen of the Lancaster had been deprived of freedom of the forest which they had purchased from King Richard, while the burgesses of Preston complained that they had lost privileges which they had received from John when Count of Mortain and others alleged that they had been dispossessed of lands granted to them by John when he was lord of Lancaster.

The History of the County Palatine and Duchy of Lancashire, by Ed. Baines, 1836, p.245:

However, John confiscated and sold Theobald’s Irish estates to one of his favourites, William de Braose, one of the most powerful barons in John’s court. His lands were not restored until January 1202, when, with the assistance of Hubert, Theobald recovered his Irish estates in Munster by payment to William de Braose of 500 marks, and became mesne tenant under him (Annals of Roger de Hoveden, II, p.513; Lancashire Pipe Rolls p.172)

Annals of Roger de Hoveden (d.1201- chronicler and historian to Henry II), p.513:

Grant by William de Braosa to Theobald Walter

(le Botiller) the burgh of Kildelon (Killaloe)… the cantred of Elykaruel (the

baronies of Clonlisk and Ballybrit, co. Offaly), Eliogarty, Ormond, Ara, and

Oioney, etc. [A.D. 1201]. (Library of Ireland, Manuscript, D.27)

William de Braose later fell foul of King John, and fled when John hunted for him in Wales and Ireland. After allying himself to the Welsh Prince Llywelyn the Great and supporting him in his rebellion, William fled to France in 1210 where he died a year later. However, his wife and eldest son were captured in Scotland, and were reportedly starved to death in one of John’s dungeons. William’s fall was an example of John’s arbitrary, cruel and capricious behaviour towards his barons and probably played a role in the Baronial uprising that led to the signing of the Magna Carta.

Ormond Deed No.27:

Acknowledgement by Theobald Walter that he and his heirs owe to William de Brahusa [Braose] and his heirs, the service of 22 knights, of the land which he holds in Munster; so that if William de Brahusa be not able to acquire the lands and services which William de Burgh holds of the said Theobald within the said 5½ cantreds, same to be void. But if Theobald make good the said services, and de Brahusa acquire the said land which the said William de Burgh holds, the said lands and services to remain to Theobald and his heirs. Witnesses: Hubert Archbishop of Canterbury, Walter de Laci, William de Braosa, Philip de Braosa, Walter de Braosa, sons of William de Braosa, etc [A.D. 1201].

As soon as his Irish lands were restored, Theobald ‘proffered two palfreys for permission to go to Ireland’ in 1202-03 (Lanc. Pipe Rolls pp.167,171), and again in 1203-04:

Theobald's reconciliation with King Richard following John's insurrection in 1193/94.

As Richard spent a total of 6 months in England during his ten-year reign, his realm was administered by a Council of Regency in conjunction with a succession of chief justiciars, and his mother, Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine exercised a considerable degree of influence. Between 1193 and 1198, Hubert Walter, appointed Chief Justiciar by Richard who also ordered his election as Archbishop of Canterbury, two of the most powerful positions, secular and ecclesiastical, in the land, in effect acted as regent during Richard’s absence.

Theobald’s close relationship with John ended during John’s brief rebellion against the supporters of the captive Richard in 1193-94 when Hubert had a complete victory over John, having been engaged in the reduction of John’s castles during February and March 1194. Many of John’s Lancashire dependants who had taken part in the rebellion, gathered at Kendal in support of John, and probably surrendered themselves to Theobald upon hearing of the captive King Richard’s release from his prison in Germany. Theobald then surrendered Lancaster Castle to his brother Hubert in March 1194 who convinced Theobald to pledge his loyalty to Richard. On 30th March a great court and council was held at Nottingham at which many sheriffs were removed and others appointed, and Theobald was appointed Sheriff of Lancaster, and regranted the wapentake of Amounderness.

In August 1194, Richard made a charter allowing tournaments in England,

for the first time, on the purchase of licences- counts paying 20 silver marks,

barons 10 silver marks, soldiers with land 4 silver marks, soldiers without

land 2 silver marks, and the king ordered that, soldiers could not complete

until they paid the fee first. Hubert, the king’s justiciar, appointed Theobald

to collect the licence fees.

Chronica Magistri of Roger de

Hoveden, (ed. Wm Stubbs, 1870, v. iii, p.268):

Richard left for Normandy on the 12th May 1194, and did not

set foot in England during the remainder of his reign. In 1195-96, Theobald was

excused his quota on the three Amounderness knight’s fees, as well as Robert Grelley

on his 12 fees and Roger Constable of Chester on his 8 fees, as t'hey had

attended personally upon the King in the expedition to Normandy, together with

their knights' (Lanc. Pipe Rolls p.95).

Richard’s last five years were spent in warfare against King Philip II,

successfully fighting to reclaim the lands that Philip had taken during

Richard’s imprisonment.

Following the failure of John’s brief insurrection, John was stripped of his lands except Ireland and he fled to the Continent where he remained during Richard’s reign, serving in his brother’s campaigns in Normandy having regained his brother’s forgiveness and trust. Richard restored to him the Honour of Eye and the Earldom of Gloucester, but the honour of Lancaster was retained in the King’s lands.

Author Stephen David Church wrote a book (pub. 1999) on "The Household Knights of King John". He explored which of the men who served John when he was Count of Mortain, continued in his service during his exile, admitting that the size of John's household was much reduced during this period.

(p.20-21) “Very

few of the men who were so prominent in John’s comital ‘acta’ during the years

before 1194 stayed with the count after his fall from grace. For the most part

John’s comital household seems to have been largely disbanded. Most significant

for this discussion, two very important men in John’s comital household also

ceased to witness his ‘acta’. Theobald Walter, John’s butler of Ireland and a

man who witnessed 42 of the count’s ‘acta’ between 1185 and 1194, and Stephen

Ridel, John’s chancellor and attestor of 54 of his ‘acta’ between 1189 and

1194, witnessed nothing after 1194. Both of these men seem to have actually deserted

John for Richard on the king’s return from captivity in 1194. It seems unlikely

that these two men were the only defectors from John’s camp in 1194.

Members of

John’s comital household also kept in with the heir apparent during his years

in the wilderness. For example, …., William de Wenneval, John’s dapifer,

witnessed two ‘acta’ between 1195 and 1198, etc. With the exception of William

de Wenneval who disappears from view, each of these other men (named) entered

into the higher echelons of the royal household on John’s accession, including

William de Wenneval’s son who entered royal service as a household knight

during the Irish campaign in 1210.

There were yet

others who, although they did not seem to remain with John during the lean

years after 1194, still managed to get themselves a place in the royal

household. etc”.

It is unknown when Theobald returned to England from Normandy serving with King Richard, but in 1196-97, his father-in-law, Robert le Vavasour executed the office of Sheriff as Theobald’s deputy (Lanc. Pipe Rolls, pp. 96, 99), a role that appears to have begun the previous year, as Robert claimed an allowance for expenditure that he had laid out that year, for an equivalent amount against the current year’s expenditure.

The following

year, 1197-98 until Christmas 1198, Nicholas Pincerna officiated as Deputy

Sheriff, as Theobald acted as a justice itinerant (Lanc. Pipe

Roll, p.103). Early in 1199, Theobald appears to have been removed from

office and Stephen de Turnham received charge of the county of Lancashire.

Richard died in Normandy on 6 April 1199, after which Theobald was returned to

the office to serve the last 6 months of the fiscal year by the newly crowned King

John. Robert de Tatteshall of Lincolnshire succeeded Theobald as Sheriff of

Lancaster after Michaelmas 1199.

It was not until the end of Richard’s reign that Theobald began using the style ‘Butler of Ireland’. Whether that was due to the influence of his brother Hubert who may have requested this hereditary title for his elder brother, just before he resigned as Justiciar in 1198, or whether it was a reward by Richard to Theobald for his recent faithful service, can’t be determined. And despite John’s vindictiveness, Theobald retained this title of Butler of Ireland, no doubt with the continued support of his influential and powerful brother whom John would not dare to challenge.

It is unknown if Theobald attended or played any role in King John’s coronation, but given that, upon John’s accession, Theobald soon lost possession of Amounderness, and briefly his Irish estates, and was removed from the office of sheriff of Lancaster which he had held since 1194, it would seem that Theobald was being punished by an incensed John for his defection to Richard in 1194. Although Hubert officiated at John’s coronation in 1199, the honour of presenting the king with his first cup of wine at the coronation banquet would have fallen to the hereditary Chief Butler of England, or Pincerna Regis/Butler of the King, William d’Aubigny 3rd Earl of Arundel, a position held by the d’Aubigny family since the early reign of Henry I and would continue to hold until the death of the 11th Earl of Arundel in 1397, inherited by the Dukes of Norfolk.

Theobald’s role as Butler of Ireland was a ceremonial role only enacted when the monarch visited Ireland, which did not occur during Richard’s reign, and John did not return to Ireland until 1210, five years after Theobald’s death.

As is well known, the position of Butler of Ireland came with the special privilege known as the ‘prisage of wine’, a levy of approximately one tenth on wine imports into Ireland, which was very lucrative.

The

surname ‘le Botelier’ and then ‘Butler’ developed out of that title, Pincerna

Hibernie, over the succeeding generations.

The social rank of the office of ‘butler’ and other offices of state

Wace, a 12th century Norman poet, in his ‘Roman de Rou’, (commissioned by Henry II, devoted to William the Conqueror and the Norman conquest of England) tells us that, as early as the close of the 10th century Duke Richard of Normandy would have none but gentlemen in his household, as with the monarch, ie. senior royal officials in charge of managing a royal household - this included the highly ranked office of ‘butler’:

“Ne vot mestier de sa meisun

Duner si a gentil home nun

Gentil furent li chapelein, (chaplain- performing spiritual services for the monarch and his family, and often

carried out some administrative/ clerical tasks)

Gentil furent li escrivain, (a scribe- responsible for drawing up

acts issued in the names of the king and queen as well as a pipe roll)

Gentil furent li cunestable, (constable- governor of a royal castle- similar duties to a marshal)

E bien puissant e bien

aidable (and very powerful and very helpful):

Gentil furent li seneschal (seneschal or steward/dapifer- principal administrator responsible for the entire control of domestic

arrangements in a royal household, in charge of domestic, administrative

services and finances; enabled to make decisions and act on behalf of the king-

one of the two most senior officers of the royal household, along with the

chamberlain)

Gentil furent li marescal (marshal- in command of the king’s military forces, responsible for the stables

and horses of the household and in charge of discipline)

Gentil furent li butteiller, (butler- one of the top 4 ranked

senior officers in the royal household, in charge of the wine cellar/buttery

and a person of high social rank; served the king his wine at dinner; would present

the newly crowned king his first cup of wine as monarch; and had different

duties at different times)

Gentil furent li despensier. (dispenser- controls and distributes pantry provisions in the royal household)

Li chamberlence, e li ussier. (chamberlain- one of the two most senior offices of the royal household, responsible

for the king’s ‘chamber’ or private living quarters, taking care of the

personal well-being of the king and his family, furnishing the servants and

personnel in intimate attendance on the Sovereign, and often acting as the

King’s spokesman; ‘ussier’- the doorkeeper to the

king’s chambers, only allowing those into the chamber whom the king wanted to

see.)

Chascun iur orent liurisuns

E as granz festes dras e

duns.” (ie. the robes and fees to which we find the officers of the King’s household

entitled)

The King’s household officials were considered

of sufficient importance to witness his charters. Butlers and chamberlains and

seneschals appear in the will of King Edred who died in 955A.D, and who

bequeathed them 80 golden coins.

Another important office was Chancellor, part of the royal household

in England from the Norman Conquest, resulting from the immense pressure of

work generated by the changes in land ownership following the conquest.

Responsible for writing and applying the royal seal in the monarch’s name,

aided by royal clerks. In 1199, the

chancery began to keep the Charter Rolls, a record of all the charters issued

by the office, and then Patent Rolls and Close Rolls.

The Norman kings also appointed the office of Chief Justiciar,

invariably a great noble or churchman, who would act as regent to represent

them in the kingdom when the king was overseas, and act as the highest judge in

the royal courts, in charge of the laws of the land. The office became very

powerful and second only to the king in dignity, power and influence.

(NB. Three years after their uncle Rannulf de

Glanville resigned as Chief Justiciar due to advanced age, Theobald Walter’s

brother Hubert Walter Archbishop of Canterbury would be appointed Chief Justiciar

in 1193 until he resigned in 1198, and after John’s accession, Chancellor in

1200.)

Encyclopedia Britannica described the five great officers of state:

The seneschal, called in medieval Latin the dapifer (from daps, a feast,

and ferre, to carry), was the chief of the five great officers of state

of the French (and Norman) court between the 11th and 13th

centuries, the others being the butler, the

chamberlain, the constable and the chancellor.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica article on “Royal Household of the United Kingdom” (Michael Ray) explained the roles of the great officers of state:

The sovereign’s chief domestics, bearing

titles suggestive of purely personal service, gradually became the great

administrators of the realm. Very early in English history the royal household

can be seen falling into three main divisions: the chapel with its staff of

clerks, the hall where the daily life of the household was passed, and the

chamber where the king could retire for sleeping and privacy and where his

clothe, jewels and muniments were stored.

No account of the household staff of the

Norman kings was written down before the early years of Stephen’s reign

(1135-54) when the ‘Constitutio domus regis’ was compiled. It is primarily

concerned with the daily wage in money and the allowance of bread, wine, and

candles due to each household officer and ignores the fact that the less

important royal servants generally held land of the king in ‘sergeanty’.

The ‘Constitutio’ begins with the royal chapel

under the chancellor, who received the highest daily wage of all the king’s

officers- 5 shillings- whether he ate at the king’s expense or his own. His

second-in-command, the master of the writing office, had received tenpence, but

Henry I increased his wage to 2 shillings and gave him appropriate additions to

his allowance of bread, wine, and candle ends.

The king’s hall

was under the care of two officers of equal rank, the seneschal (steward) and

the master butler, who each received a standing wage of 5 shillings a day. When they

actually served in court and were fed at the king’s expense, their daily wage

was 3 shillings 6 pennies. Their two parallel

departments provided food and drink through a series of officers carefully

graded as to pay and allowances down to the man who counted the loaves and the

slaughterers who had no pay, but “customary food” only.

After the hall, came the chamber under the

master chamberlain, but beside him stood the treasurer, each of these officers

receiving the same pay and allowances as the seneschal and master butler. Below

them were less well-paid chamberlains: the man who looked after the king’s bed

with a man and packhorse for its transport, the king’s tailor, and his bath

attendant. The appearance here of the treasurer- as the head of the new

financial department, the exchequer- shows that in origin the treasury was

regarded as a household department. While the chancery and exchequer were still

departments of the household, a hundred years later, the enormous momentum of a

developing nation, had carried out of court, and the household had been obliged

to create a financial and clerical department of its own, hence the gradual

appearance in Henry II’s reign of the chamber as the department which received

and spent money on household and national business.

The ‘Constitutio’ concludes with the two

departments which between them cared for the safety, peace, order, and comfort

of the household, and for the king’s sport. The chief constable had the same pay

and allowances as the master chamberlain, but the marshal had not yet achieved

the higher rate. He had to keep the tallies (the receipts) for all the gifts

and liveries made from the king’s treasury and chamber and oversee the

hearthman who made the fire in the hall from Michaelmas to Easter.

Already at the beginning of the 12th

century, the chief household officers, important barons in their own right, had

become too great to perform their household tasks as a matter of routine. On

occasions of high ceremony, and in particular at a coronation, there was fierce

competition among the greatest magnates of the land for the right to discharge

any household duties which they could claim by inheritance.

As we know, the position of Butler of Ireland came with the special privilege known as the ‘prisage of wine’, a levy of approximately one tenth on wine imports into Ireland. Another special honour was that the Butler was required to serve the first glass of wine to the king after his coronation, and was further rewarded with a selection of the silver plate at the banquet.

Origins

of the Walter family

For centuries, researchers of the Irish Butler/Ormonde family have been searching for the origins of Theobald Walter, with little success. Records revealed that Theobald’s father was named Hervey Walter, and Hervey’s father was also named Hervey. The Walter family flourished in the period from the late 11th to the early 13th century. However, records dating back to that period of time are few, making research difficult.

Thomas Carte published a comprehensive study of the Irish Butlers, “The Life of James Duke of Ormond” in 1736, republished in 1851. In the Introduction, Carte wrote that ‘nobody who has wrote on the subject of Herveus, father of Herveus Walter, seems to have had any notion of such a person’. He then discussed the numerous theories that have been written in past centuries of the origins of the Irish Butlers, none of which have been proven due to lack of documentary evidence, particularly birth, death or marriage records, in the 11th and 12th centuries. The primary sources of evidence are taken from official land holding records and fees due to the Crown, and ecclesiastical records of that time, very few of which date back to the 11th and early 12th centuries, and which rarely name wives or daughters, making research difficult.

In the 20th century, Butler family historians, the late Theobald Blake Butler and Patrick Lord Dunboyne, studied these families thoroughly over several decades, making extraordinary contributions to our genealogical knowledge of Butler families down the centuries, but again found it difficult to pinpoint the first Norman settler in the line. Blake Butler’s conclusion, based on Domesday Book land records, and lands subsequently held by the Walter family in Suffolk, was that the first in the line was probably a Norman named Walter who held a close relationship to Robert Malet, a major land holder as tenant-in-chief in Co. Suffolk in Domesday from whom Walter sub-tenanted several lands, and there are many good arguments for this conclusion.

Apart from this Norman named just ‘Walter’, there were several other men also named ‘Walter’ who were sub-tenants of Malet. He was possibly ‘Walter the crossbowman’ or walter filius Aubrey /Albrici, both of whom held lands in close proximity to this ‘Walter’s’ lands and therefore could be the same person. This ‘Walter’ could also be Walter de Caen who was Robert Malet’s most prolific sub-tenant in Suffolk and Norfolk and a close associate (if not a relative) and also held lands in this same area, a conclusion Theobald Blake Butler came to in later years.

There is also an unsubstantiated claim by a few historians that he was Walter de Glanville, and this theory should be considered given the close relationship between the Walter and de Glanville families.

However, as will be shown, the available records are inconclusive. He may have just been a Norman knight simply named Walter.

The analysis in the 2nd and 3rd chapters, looks at the likelihood of the various ancestral origins claimed in numerous pedigrees produced through the centuries, including a thorough investigation of the most popular theories of descent from several Normans named Walter living in Suffolk, as well as the de Clares, the Beckets, the de Glanvilles, and individuals named Hervey and Hubert, suggested by some historians as Norman ancestors.

But firstly, the information and records found on the extended Walter family need to be explored in detail to establish who were all the known family members, where they were living, what lands they held, and who their close associates

THE ROLE OF RANNULF DE GLANVILLE IN THE WALTER FAMILY

What circumstances preceded Theobald Walter being granted the title of Pincerna Hibernie/Le Botelier of Ireland which led his descendants to assume the surname, Butler?

Theobald

and his brother Hubert were educated in the household of their uncle Rannulf

de Glanville Chief Justiciar of England under Henry II. Henry’s youngest

son, Prince John (born circa December 1166-1167) also joined Rannulf’s

household in 1179, aged twelve, where he was to remain until his education was

complete. The apprenticeship in the household of Rannulf must have had a

profound impact on John, and he appears to have developed a long-lasting,

albeit somewhat fractious attachment to the people in Rannulf’s household.

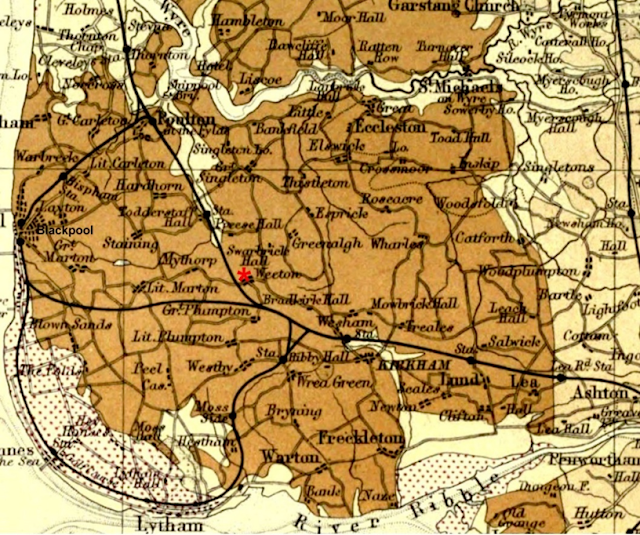

Rannulf de Glanville, the sheriff of Lancashire and Westmoreland, was rewarded for capturing the Scottish King William the Lion in 1174, by his appointment as a justice of the King’s Court, then the role of Chief Justiciar in 1180, and held the office until Henry’s death in 1189 which meant that he was the most powerful man in the realm after the king. He sat at the Exchequer, and, in the king’s absence, presided over royal councils, the king’s courts, and acted as military commander, so he was the ideal tutor for John. His elder nephew, Theobald Walter, would have trained as a knight in Rannulf's household, and no doubt was under Rannulf's command when the Scottish King was captured. Theobald owed 1 knight's fee, ie. the service of a knight, for his Weeton fee which he had inherited from his grandfather.

Rannulf's younger nephew Hubert Walter received his administrative and legal training under Rannulf’s tutelage and rose to prominence around the royal court during the 1180’s, beginning his career as one of the King's clerks. As Rannulf’s chief deputy, Hubert was involved in the full range of administrative business for which the justiciar was responsible, serving as one of the barons of the exchequer during the 1180’s and sitting regularly with Rannulf and others as a justice of the exchequer court, developing considerable expertise as a justice during those years. Henry II also employed him in chancery and diplomatic work, conveying messages between England and the king of France.

Rannulf and Theobald were at Chinon Castle in July 1189 when they both witnessed Henry’s confirmation Charter to Coverham Priory, shortly before Henry’s death there on 6 July.

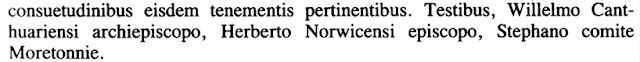

Complete

Charter:

Wikipedia;

and, ‘A

History of the Co. of York’ v.3, ed. Wm Page, 1974, pp 243:

Coverham

Abbey in Nth Yorkshire was a Premonstratensian monastery originally founded in

Swainby c.1190 (error- see Henry II’s charter) by Helewise daughter of

Rannulf de Glanville, wife of Robert fitzRalph 3rd Lord of

Middleham, with the consent of her son and heir Waleran then living. She

died in 1195 and was buried at Swainby. It was refounded at Coverham in about

1212 by her son Ranulf fitzRobert who had the body of his late mother

reinterred in the chapel house at Coverham.

(NB

in Domesday, the single manor of Swainby was part of Count Alan’s Honour of

Richmond, tenanted by Ribald Lord of Middleham)

Robert Wm Eyton, in his “Court, Household and itinerary of King Henry II” (1878- p.297) reported the foundation differently:

5

July 1189. K. Henry is carried from the conference of Azay, in a dying state,

to Chinon, where he learns that his son John has been beguiled to the

allegiance of Philip.

A

Royal Charter, dated at Chinon, confirms a grant by Walleran fitzRobert to Theobald

Walter’s nascent foundation at Swainby (Lincolnshire). It is attested by

William Dean of Moretain; Ralph Archdeacon of Colchester; William earl of

Arundel; Rannulf de Glanvill, Theobald Walter, Stephen de Turnham, Ralph

fitzStephen, Gilbert fitzReinfrid Dapifer; Walleran fitzRobert (son of Helewise), Henry

de Cornhill, and Gilbert d’Aumari (Monasticon, vii, 920), at Chinon.

NB.

All other references indicate that Helewise was the founder with the consent of

her son and heir, Waleran.

One of the other witnesses to the Charter, Henry de Cornhill (1135-1193) a royal official under Henry II, who was in charge of purchasing cloth and other items for the royal household, was known to be present at Henry’s deathbed at Chinon in July 1189 (Wikipedia), as was a second witness Stephen de Turneham (d.1215) who was seneschal of Anjou and was in charge of the royal treasure which Richard demanded he hand over after his father’s death. Stephen would order the burning of Le Mans where the king was staying when they were attacked by his son Richard’s forces in June 1189.

Author William Glanville-Richards confirms in his book on the de Glanvilles, that Rannulf (and Theobald) were with Henry in the last tumultuous weeks of his life, (Records of the Anglo-Norman House of Glanville, London 1882, p.35-36), in which he wrote:

In

July 1188, we find Rannulf collecting an army of earls, barons and knights, and

a large number of Welshmen, and sending them to Henry in Normandy who was then

at war with France.

In

January 1189 the Archbishop of Canterbury (Baldwin), and his vicar Gilbert de

Glanville Bishop of Rochester, preached before the King and assembled lords,

the subject being “On the Mystery of the Cross”, they pointing out that all

those who professed to be followers of Jesus, the sin and shame it was for them

to all His sepulcher to remain in the followers of Mahomet, and exhorted all,

or whatever station, from the King to the meanest of his subjects, to at once

assume the sign of the Cross, and join those blessed expeditions, who were now

marching towards Jerusalem, by assisting in the undertaking, and to insure

themselves glory in this world and eternal salvation in the next.” Henry

himself promised to march there was soon as he was able to leave the kingdom.

But “what the astonishment”, writes Lord Campbell, “of all present, when the Chief

Justiciary Randulph de Glanville, known to be vigorous and energetic, but not

suspected of enthusiasm, now well stricken in years, who had spent the best

part of his life in studying the law and administering justice, who had a wife

and many children and grandchildren, the objects of his tender attachment- rose

up as soon as the King had concluded his speech, and asked the Archbishop to

invest him with the Cross- was enlisted as a Crusader with all the vows and

rites used on such a solemn occasion, so much in earnest was he that he wished

forthwith to set forward for the Holy Land.”

Glanville

did not set out at once as he desired, as weighty matters of State kept him

longer in England. Prince Richard had again rebelled against his father, and had

taken up the cause of Philip King of France, due to the refusal of Henry to

deliver up Alice, sister of Philip, and the affianced bride of Richard.

Glanville, at the command of the King, therefore waited until tranquility

should be restored; but before this was consummated King Henry died at Chinon

‘of a broken heart’ on July 6, 1189. Glanville was present at the scene

“when on the approach of Richard blood gushed from the dead body, in token, as

people said, that the son had been the murderer of his father.

The

new monarch, now stung with remorse, renounced all the late companions of his

youth who had so misled him, and offered to confirm all his father’s councilors

in their offices. This offer was firmly refused by Glanville, who had serious

misgivings as to the sincerity of Richard, and who, now wearing the Cross, was

bound by his vow, as well as incited by his inclination, to set forward for the

recovery of Jerusalem. However, he discharged the duties of his office for some

weeks till a successor might be appointed, and he attended, with the rank of

Chief Justiciar, at Richard’s coronation, when he exerted himself to the utmost

to restrain the people from the massacre of the Jews, which disgraced that

solemnity. Glanville was not only witness to King Henry’s will, but also one of

the executors appointed under it.

We know that Richard’s first care when he landed at Portsmouth in 1189, was to seize his father’s treasury at Winchester Castle, and that Glanville gave up to the King the enormous treasury of £900,000, besides jewels etc. He was likewise a witness to a Charter of Richard I to John de Alençon in Normandy dated April 11, 1190, before traveling on towards Jerusalem in the company of Baldwin Archbishop of Canterbury, and Hubert Walter his nephew Bishop of Salisbury, and landed at Tyre, about Michaelmas 1190, all of them having been despatched by King Richard to assist at the siege of Acre, and having previously, according to some accounts, accompanied the King himself through France as far as Marseilles. Rannulf and his companions reached Acre, before which Archbishop Baldwin first fell a victim, and then, before the end of the year, Rannulf de Glanville, but not as sometimes stated, in the heat of battle. Glanville had accumulated a very great fortune which enabled him to travel to the Holy Land as a noble of the highest rank.”

The

death of Henry II

Our

knowledge of these accounts came from the pen of contemporary chroniclers,

Giraldus Cambrensis (Gerald of Wales) who was present during these events, and

Gervase a monk of Canterbury.

King

Phillip of France played on the rifts in this tumultuous family, suggesting to

Richard that his father’s favourite was John and that Henry wished to support

John’s succession. Richard demanded full recognition of his position as heir,

which Henry refused. Further rebellion ensued. Henry with a handful of faithful

followers shut himself up at his birthplace, Le Mans and fell ill with a fever

whilst there. Richard and Phillip proceeded to attack Le Mans. On 11 June, the

defenders, ordered by Stephen de Turneham, set fire to parts of the town

suburbs to impede their progress, which quickly spread through the city,

forcing Henry and his followers to flee. While covering Henry’s retreat from Le

Mans to Chinon, William Marshall unhorsed Richard and could have killed the

prince, but killed his horse instead to make the point. He was to be the only

man ever to unhorse Richard.

Henry

sent Rannulf de Glanville (probably accompanied by Theobald) back to England to

collect forces, and ‘compel soldiers and the poor to come over’ while

Henry turned back to Chinon. Rannulf got little satisfaction from the clergy at

Canterbury, and having stormed out of the meeting, he hastened to London to

gather together a force and organize their transmission to the king in Normandy

(according to Gervase of Canterbury- Historical Works of Gervase of

Canterbury, vol. I, The Chronicle of the Reigns of Stephen, Henry II and

Richard I, ed. Wm Stubbs, London 1879, pp.447-450).

Rannulf

then returned to the King’s side at Chinon. It was at this time that Henry made

the confirmation charter to Coversham Abbey endorsing the grant by Rannulf’s

grandson Waleran fitzRobert, and witnessed by Rannulf and Theobald and others

who were with the King at the end.

Fever stricken, Henry lay there in Chinon while Philip and Richard stormed Tours. Dragging himself out of bed, he was humiliatingly forced to meet them and agree to terms- to pardon all those who conspired against him, renew his homage to Philip, and, most hurtful of all, to acknowledge Richard as his heir to all his lands, and to give him the kiss of peace, with Henry muttering “God grant that I die not until I have avenged myself on thee” (according to Giraldus Cambrensis*). Henry’s only request was a list of those who had rebelled against him which was delivered to him at Chinon. William Marshall began to read out the list, at the top of which was his beloved son John, the son he had trusted and fought for had deserted him. Utterly crushed, Henry did not wish to hear the other names on the list. Heart-broken and disillusioned, his health quickly deteriorated, and he lay tossing in anguish and delirium, cursing his sons and himself, breathing his last on 6th July 1189. According to Giraldus Cambrensis*, Henry’s last words were “Shame on a conquered king; for shame”- “Proh pudor de Rege victo! Proh pudor!” - as he turned to the wall and died. Other reports have him saying “Now let the world go as it will; I care for nothing more.” And as he sank into a delirium: “Shame on a conquered king! Cursed be the day I was born! Cursed be the sons I leave!” Henry’s only family present was his beloved illegitimate son Geoffrey who had tenderly cared for him in his last days (Geoffrey would unwillingly become Archbishop of York under Richard’s orders). Henry’s body was taken to the Abbey of Fontevrault in Anjou for burial, which was to become the mausoleum of the Angevin Kings.

*Giraldus Cambrensis De Instructione Principum: Libri III, ed. J.S. Brewer, (London 1848) p.150-151.

The

editor wrote in the preface: For some

years Giraldus was the daily companion of Baldwin Archbishop of Canterbury. In

1188 Giraldus accompanied Archbishop Baldwin, then engaged in preaching the

Crusades. Subsequently, when the war broke out between Prince Richard and his

father Henry, which ended in the death of Henry, Giraldus was sent over to

France, as a mediator with Archbishop Baldwin and Ranulf de Glanville;

so that he had every facility for ascertaining the truth of what he has

narrated respecting the death of the King, and the cause of his dissension with

his sons- means for ascertaining the truth, such as no author possessed at the

time.

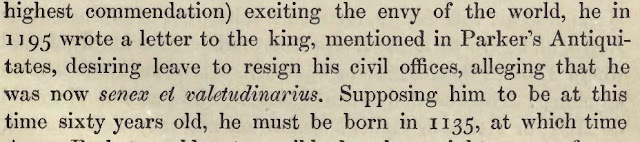

Hubert Walter's rise in status under Rannulf de Glanville

Hubert’s meteoric rise within the church began with his first appointment as rector of Halifax in 1185, promoted in 1186 as dean of York Cathedral, then appointed Bishop of Salisbury in 1189 by the newly crowned King Richard, culminating with his appointment as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1193. Hubert’s rise to ultimate power, both secular and ecclesiastic, followed the accession of Richard I.

According to C.R. Cheney in his book ('Hubert Walter' 1976, pp18-21), Hubert first appears in 1181 in the company of his uncle Rannulf, now chief justiciar, and Osbert de Glanvill at the king’s court at Westminster shortly before Henry II went overseas, entrusting England to the justiciar for the next two years. This particular transaction was witnessed by three bishops, Richard of Winchester, Geoffrey of Ely and John of Norwich, then Rannulf de Glanville the new justiciar, Richard fitzNeal the king’s treasurer, William de Vere a royal judge, and Hubert Walter, and three well-known judges, followed by Silvester (?)de Glanville and a dozen other men. In 1182, a similar gathering in the king’s chamber at Westminster approved a grant to the cathedral church of Wells, in the presence of Rannulf Glanvill justiciar of the lord king and many others of the exchequer. The first witnesses were a distinguished half-dozen archdeacons, followed immediately by ‘Osbert de Camera, Hubert Walter, and William de Glanvill, clerks’. Hubert was with Rannulf in the King’s court at Woodstock in August 1184, and sat on the bench at Westminster in 1184, 1185, 1187, 1188 and 1189. He took money to Maurice de Berkeley in South Wales in 1184, or 1185. Henry II employed him several times to negotiate with the monks of Christ Church, Canterbury over disputes.

He was at court with the king on 10 April 1185, on the eve of Henry II’s crossing from Dover to France, and two years later he crossed the Channel on the king’s service. In February 1189, when Hubert Walter was with the king at Le Mans, he was doing chancery business. In March that year, he deputized for the justiciar who was overseas with the king.

Gervase of Canterbury wrote that Hubert shared with Rannulf de Glanvill in the government of England (Gervaise, II, 406), and this, with the fact that Hubert was nephew to Rannulf, suggested to some historians that Hubert might be the author of the anonymous ‘treatise on the laws and customs of the realm of England’. It is attributed to the years 1187-9, at the end of Henry II’s reign.

While Rannulf de Glanville is credited with the authorship of ‘Tractatus de legibus et consuetudinibus regni Angliae’, often called ‘Glanvill treatise’, a legal treatise on the laws and constitutions of the English written 1187-89, some historians, such as W.L. Warren, theorize that Hubert may have been the author, while others have suggested Osbert fitzHervey, and Geoffrey fitzPeter who replaced Hubert as Justiciar and had a strong knowledge of the law, could have contributed.

While there is debate over the actual authorship of all or part of the ‘Tractatus’, the legal opinions of Hubert Walter are cited four times out of the twelve, two by Rannulf and two by Osbert fitzHervey. Hubert’s close working relationship with Rannulf over a long period of time, and Hubert’s knowledge of the law and his organisational skills, demonstrated in his roles as Justiciar and Chancellor, certainly recommend his candidacy as the author.

As Wikipedia describes, “it was revolutionary in its systematic codification that defined legal processes and introduced writs, innovations that survive to the present day. It is considered a book of authority in English common law.”

Glanville's 'Tractatus' (‘Glanvil de Legibus’) was first printed in a book in 1554 edited by Richard Tottel. The image is of an original first edition.

Original first edition of ‘Tractatus de legibus et consuetudinibus regni Angliae’

When Richard went on Crusade in the summer of 1190, Rannulf de Glanville, Baldwin Archbishop of Canterbury and Hubert Walter bishop of Salisbury preceded him to Acre. The aging Rannulf and Baldwin soon died of sickness in the Holy Land, and Hubert was given the task of reorganizing and financing the starving army using the deceased archbishop’s possessions, handling a variety of sensitive negotiations between competing crusade leaders, and negotiating with the Muslim leader Saladin, which he accomplished with great skill over the following two years. He led sorties against Saladin’s camp, distinguishing himself in several battles, and also ministered to the religious needs of the army which raised morale. Hubert’s stature in the crusading army continued to grow after the arrival of Richard who found the army in far better shape than it had been six months before. His negotiation of a more permanent peace treaty with Saladin restored Latin services in the Holy Land and guaranteed free access for western Christians to Jerusalem, after which Hubert then fulfilled his crusader’s vow by leading one of the first contingents of Western pilgrims to visit Jerusalem. Hubert and King Richard both left the Holy Land in October 1192, with Hubert visiting Pope Celestine III in Rome in January 1193, where rumours of Richard’s captivity first reached him.

Having been captured on his return from the Crusade in October 1192 and held in captivity by the Holy Roman Emperor, Richard was found at Ochesenfurt on the River Main in March 1193 by Hubert accompanied by the exchequer clerk, and were the first of his subjects to reach him. He immediately began negotiating terms for Richard’s release. Having observed Hubert’s extraordinary diplomacy, leadership and organizational skills during the Crusade, Richard gave him letters appointing him as Chief Justiciar and ordering the church hierarchy to elect Hubert as archbishop of Canterbury, whereupon Hubert returned to England to raise the enormous ransom demanded for Richard’s release.

Biographer Robert Stacey wrote: 'The 4 1/2 years of Hubert Walter's justiciarship were characterized by the systematization of existing procedures and the creation of new ones. Under his justiciarship, the king's court became an increasingly professionalized and specialised set of institutions. This continued in chancery after Hubert's appointment as chancellor on John's accession to the throne.' (ref: Walter, Hubert, by Robert C. Stacey, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004)

As reported by contemporary chroniclers, Hubert is well known to have kept John’s excesses on a tight leash until Hubert’s death in July 1205 (only a few weeks before his brother Theobald’s death in August-September, before Michaelmas), which is an indication of Hubert’s influence over John. Having virtually governed England for Richard for the six years prior to John’s accession, Hubert, well known for his masterful temperament, was inclined to act rather dictatorial than deferential towards John, so much so, that when he received tidings of Hubert’s death, John supposedly rejoiced and exclaimed “Now for the first time I am King of England!” (“Nunc primum sum rex Angliæ!”), according to contemporary chronicler Matthew Paris.

THEOBALD'S FIRST VISIT TO IRELAND

Although at least twenty to thirty years his senior, Theobald became a favourite of Prince John who was granted the lordship of Ireland by his father King Henry II in 1177. Theobald and Rannulf accompanied John, along with 300 knights, on his first visit to Ireland in 1185, the freight of Theobald's equipment being paid for by the royal exchequer. Theobald's men, along with an Anglo-Norman party from Cork led by Geoffrey de Cogan, were responsible for the assassination of Diarmait MacCarthaig (Dermot MacCarthy), king of Desmond (co. Cork and most of Co. Kerry), during a parley in 1185.

Theobald and Rannulf were granted 5 ½ cantreds of land in Limerick,

jointly held, for the service of 22 knight’s fees, which subsequently became

Theobald’s land as sole beneficiary. Theobald was also granted the castle and

vill of Arklow and the manor of Tullach Ua Felmeda in Carlow, and land centered

on Gowran, Kilkenny, between 1185 and 1189, the deed witnessed by Ranulf de

Glanville, and Hubert [Walter] Dean of York. Notably Theobald is not described

as ‘pincerna’ is this document. (Ormond Deed No. 17)

Ormond Deed No. 17:

Giraldus Cambrensis (Gerald of Wales)

accompanied John’s entourage to Ireland and wrote of his experiences there, ‘Expugnatio

Hibernica’, which was translated in ‘The English Conquest of Ireland

A.D. 1166-1185’, Pt 1 ed. by Frederick Furnivall, London 1896, pp.149-151:

Gerald described John’s companions as “Talkative,

boastful, enormous swearers, bribe-takers, and insolent”.

Geraldus reporting that Dermod MacCarthy, Prince of

Desmonde (King of Cork), and others attending a parley in Cork, were slain

by Theobald Walter and his men in 1185:

‘Of the Prynce of Desmonde, Dermot Maccarthy,

that with many othyr in a parlement besyde Corke, through Tybaud Wauter and the

meny (men) of Corke, was y-Slayn.’

In the side column:

‘A.D. 1185 in colloquio prope Coreagiam, a Corcagiensibus et Theobaldi Gualteri familia ferro peremptis.’ (translated as: ‘A.D.1185. In a conference near Coreagia, in Cork, Theobald Walter’s family were slain by the sword’.

They may have been accompanied to Ireland by a possible son and heir of

Rannulf named William de Glanville who was subsequently killed in the skirmish. He was Theobald's cousin. There is also the possibility that Theobald's younger brother Roger Walter may have also accompanied them, as he appears to have held a close relationship to William:

M.T. Flannagan (Butler [Walter], Theobald, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 2004) noted, “An entry in the annals of Loch Cé, recording the killing in 1185 by Domnall Ó Briain, king of Thomond, of a foster brother of Prince John, suggests that a son of Ranulf de Glanville was included among John's entourage in Ireland.”

viz. " in which very many foreigners were slain, along with the foster-brother of the son of the king of the Saxons."

Records indicate that this son of Rannulf named William de Glanville appears to have died in the mid to late 1180’s, and may have died on this excursion to Ireland. He was probably the William de Glanville who witnessed Hervey Walter’s charter to Butley priory in c.1171-77. In Hervey’s charter to Butley, he dedicated the charter partly for the souls of “Rannulfi de Glanvill et Berte sponse sue et filiorum suorum” which translates as 'Rannulf de Glanvill and Berthe his wife and their sons'. The editor of the Cartulary, R. Mortimer, noted that "this seems to be the only indication that Rannulf de Glanville had sons; he was succeeded by his three daughters". (The Cartulary of Leiston Abbey and Butley Priory Charters, ed R.H. Mortimer, 1979, p.151, No.146)

He was also probably the William de Glanville who shared a farm in Norfolk with Theobald’s brother Roger Walter which they donated to the nuns of Watton monastery in the charter of John de Birkin and his wife Joan and her sister, William’s wife Dionysia [Lenveise] who remarried c.1189. (Wm Glanville Richards, Records of the Anglo-Norman House of Glanville, 1882, p.10).