NB. clicking on an image will open a higher resolution image

CONTENTS:

Introduction: Explanation of land tenure after the Conquest, and in

particular lands held by the Malet family in Counties Suffolk and Norfolk as

tenants-in-chief in the Domesday Book

(A) Walter ‘who held of this manor’

(B) Walter the crossbowman

(C) Walter de Caen

(D) Walter fitzGrip

(E) Others named ‘Walter’ who held lands in East Anglia in Domesday:

The previous

blog chapter concentrated on the evidence available on the immediate family of

Theobald Walter 1st Butler of Ireland who was the ancestor of

the Ormond Butlers and the other Irish Butler aristocratic lines such as Barons

Dunboyne, Viscounts Mountgarrett, Earls of Carrick, Viscounts Galmoy, Baronets

of Cloughgrennan, Barons Cahir, etc., and many Butlers of Irish descent.

However, while the Butler surname in Ireland developed from the hereditary

title of Butler of Ireland, Theobald’s surname was Walter, and this chapter

explores the possible Norman origins and ancestry of this Walter family.

As discussed in the previous blog chapter, Theobald’s father, brothers, uncle and cousin, and possibly grandfather (in one record) all carried the unusual surname of ‘Walter’, as evidenced in all records of this family. No-one in this extended family was ever referred to as ‘FitzWalter’ in the records which as most unusual for that period of time.

To determine which of the many ‘Walters’ named in the Domesday survey could be relevant to our quest, we can only look at the lands, possibly ancestral, held by the ‘Walter’ family in co. Suffolk in the 1100’s which correspond with the lands held by a Norman land-holder named ‘Walter’ in Domesday.

While this is not an accurate method, it is the only approach available to us, given the lack of records for that period of time.

THE SURNAME ORIGINS OF THE WALTER FAMILY

Authors, Pollock

and Maitland in their ‘History of English Law Before the Time of

Edward I’ (vol.1. pp.164-65, 1903), discuss the archbishop of Canterbury

Hubert Walter’s name: ‘Now the name ‘Hubertus Walteri’ was not merely an

uncommon name, it was a name of exceedingly uncommon kind. ‘Hubertus

filius Walteri’ would of course be a name of the commonest kind, but the

omission of the ‘filius’ is, among men of gentle birth, an almost distinctive

mark of a particular family, that to which the great archbishop belonged.’

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (DNB- biography of Hubert Walter, by Robert C. Stacey, 2004) makes the statement that ‘Hervey Walter was a Norfolk knight of middling status’. In other words, Hervey’s Norman ancestor was not related to the royal family of the Conqueror and therefore did not hold high status, but was probably one of the lesser ranked knights who accompanied William at the conquest in 1066, or was one of the numerous Norman settlers who followed soon after the Conquest, and possibly held lands under one of the tenants-in-chief granted lands in the Domesday survey. Their rise in status in the late 12th century was due to their relationship with Rannulf de Glanville Chief Justiciar of England and his close association with King Henry II and his sons and heirs, Richard and John. They must have held sufficient status for Theobald de Valoines, Lord of Parham, to grant the hand of one of his daughters to Hervey Walter. The de Valoines, the de Glanvilles and the Walters appear to have been of the same social level in Suffolk in the early 1100’s. And therefore, the Walter ancestor must have held lands in Suffolk/Norfolk in Domesday just as the Valoines and Glanville ancestors held lands in Suffolk/Norfolk under tenants-in-chief such as Robert Malet and Count Alan of Brittany.

The origin of the surname Walter remains the prime question.

How did this

family acquire this singular surname, and from whom did the surname Walter

originate?

Why did it

differ to the normal form of ‘filius Walter’ or fitzWalter?

Was it taken

from the paternal or maternal line?

Was it a case of

the name coming from a wife of superior status who was an heiress, or was the

name taken as a younger son to differentiate from the senior line?

Or was it

adopted to differentiate from other lines of FitzWalters of whom there were

several, including the eldest son of Walter de Caen named Robert fitzWalter,

and the fitzWalter brothers, sons of Walter fitzOtho Castellan of Windsor and

tenant-in-chief of 21 manors in Domesday; and the later Robert fitzWalter of Dunmow Castle (descendant of the de Clare family), one of the leaders of the baronial opposition against King John?

The interesting point is that surnames in that era were fluid and often changed with each new generation to reflect their father’s name, or by taking the names of their estates as family appellatives, yet every member of this extended family for at least three generations used the same singular surname of Walter. One would think that this must have been in honour of their forebear, and the family’s desire to differentiate their family line from descendant lines from different ancestors named Walter, a common Norman name at that time. Notably, while there were several unrelated families of fitzWalters, this particular family was the only faily that held the singular surname of Walter in Norman England.

One of the few

surviving records of the 11th century was William the Conqueror’s

magnificent survey of all landholders in England pre and post Conquest, called

the Domesday Book. The lands in co. Suffolk belonging to Walter family members

in the 12th century may be of importance in determining their

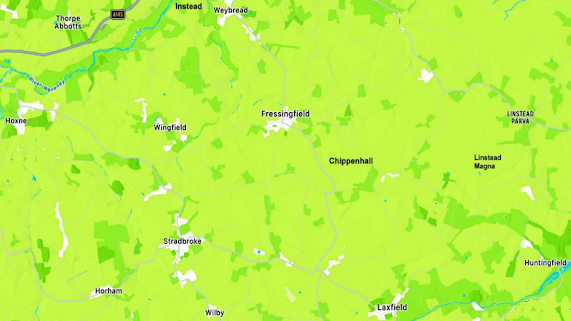

ancestry, namely at WINGFIELD, INSTEAD (part of Weybread), and possibly STRADBROKE (the unidentified ‘Sikebro’ in

Hervey’s charter to Butley Priory) all held by Hervey Walter, and at FRESSINGFIELD belonging to the junior Walter line

(viz. Hubert Walter the elder and his son Peter Walter whose manor of

Snapeshall was in Fressingfield). They were all located in the

small area in the Hundred of Bishop in north Suffolk, near EYE and belonging

to the Honour of Eye held by tenant-in-chief Robert Malet until c.1106, then held

by the Crown, and from c.1115 by Stephen Count of Mortain, nephew and heir to King

Henry I. These lands will be examined in detail, the importance of which will

become apparent as we look at the Domesday Book records for these lands, and

determine who held them.

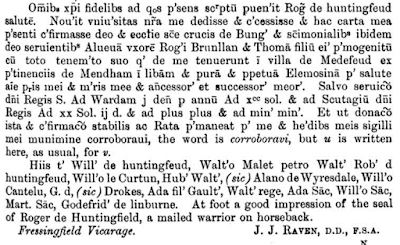

Map of East Suffolk showing close proximity of these lands held by the Walter family

The documentary

evidence of Hervey Walter’s Suffolk lands occurs in the Butley Priory Cartulary

–

The Cartulary

of Leiston Abbey and Butler Priory Charters, ed R.H. Mortimer, 1979, p.151-

Charter No. 146; dated c.1171-77:

In Charter No. 147 in the same cartulary, a Gilbert de Hawkdon granted 6d rent in Instead to Butley Priory ‘by the will of my lord Theobald Walter’, confirming that Theobald held Instead in his lifetime. The charter was witnessed by Peter Walter who donated rent from his mill at Instead to West Dereham Abbey founded by his cousin Hubert Walter (viz. son of Hervey Walter).

Peter Walter’s Fressingfield lands were inherited from his father Hubert Walter the elder, and as he personally stated in a charter, his ‘predecessors’, the tithes of which were donated to Eye Priory.

Eye Priory

Cartulary and Charters, I, ed. V. Brown, 1994, p.231

Charter No.319- Peter Walter

Date: c.1180’s:

One of several

Eye Priory confirmation charters referring to Peter’s father Hubert Walter’s

land in Fressingfield, named Snapeshall, from which he donated the tithe to Eye

Priory:

(Eye Cart., pp.43-44)

Charter No.40- Bishop

of Norwich

Date: c.1155-61:

A suit in 1209 between Peter Walter son of Hubert Walter ('Peter filius Hubert'),

and the abbot of West Dereham Abbey confirmed that Peter held land in Instead

and in Weybread that he held from his ancestors (under recognition of ‘mort

d’ancestor’ = death of an ancestor), the rents of which he had donated to his cousin

Hubert Walter’s foundation charter of Dereham in the 1190’s. Notably, this suit

occurred after the deaths of Theobald and his brother Hubert, and it would also appear, the deaths of their brothers Roger and Hamon, which would explain the inheritance of their mutual ancestor's (viz. Hervey's) lands by Peter Walter.

Norfolk

Final concord at St

Edmunds, 19 April 1209.

Between Peter son of

Hubert (Petrum filium Huberti), the claimant, and Henry abbot of Dereham,

the holder of 20 acres with appurtenances in Ysted/Instead and three

shillings worth of rent in Weybread, under the recognition of ‘mort

d’ancestor’.

(Feet

of Fines for the County of Norfolk for the reign of King John 1201-1215, and

for the County of Suffolk 1199-1214, ed. Barbara Dodwell, London 1958

(p.238 No. 497 [Case 154, File 30, No. 435])

What we don’t know is in what period of time these adjacent lands in the Hundred of Bishops/Hoxne were acquired by the Walter family, whether inherited from a Norman settler or granted by Stephen Count of Mortain at the time he granted them the fee of Weeton in Lancashire. Due to lack of records, this question will not be resolved, but as Peter Walter confirmed the donation of the tithes of his demesne lands in Fressingfield as the ‘gift of his predecessors’ which implies more than just his father Hubert, we should explore the possibility that the Suffolk lands and their ‘Walter’ surname were inherited from a Norman settler. Plus, the fact that the de Glanvilles and the de Valoines inherited their lands in Suffolk and Norfolk from their ancestors who held lands in the Domesday Book.

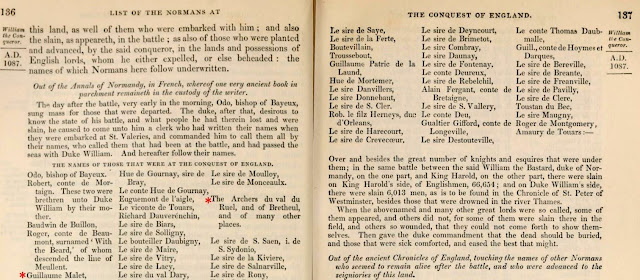

EXPLANATION OF LAND TENURE AFTER THE CONQUEST, AND IN PARTICULAR LANDS HELD BY THE MALET FAMILY IN COUNTIES SUFFOLK AND NORFOLK AS TENANTS-IN-CHIEF IN THE DOMESDAY BOOK

King William established his favoured followers as barons by enfeoffing them as tenants-in-chief with great fiefdoms. Lands forming a barony were often located in several different counties, but usually a more concentrated cluster existed in a specific county. The name of such a barony is generally deemed to be the name of the chief manor within it, generally assumed to have been the seat or chief residence of the first baron. The feudal obligation imposed by the grant of a barony was set as a quota of knights to be provided for the king’s service. Commonly, he found these knights by splitting his barony into several fiefs, into each of which he would sub-enfeoff one knight, by the tenure of knight-service. This tenure gave the knight use of the fief and all its revenues, on condition that he should provide to the baron, now his overlord, 40 days of military service, complete with retinue of esquires, horses and armour. The fief so allotted is known as a knight’s fee. Scutage was a medieval tax levied on holders of knight’s fees, whereby the knights were allowed to ‘buy-out’ of the military service, and first existed under the reigns of Henry I and Stephen.

If the barony contained a significant castle and was especially large, consisting of more than 20 knight’s fees, then it was termed an ‘honour’, with the castle giving its name to the honour and serving as its administrative headquarters. (Wikipedia)

The main landholders listed in the Domesday Book were tenants-in-chief, either King William himself, or one of around 1400 people who held land directly from the Crown, mostly higher status Norman knights and lords, and in turn, the tenants-in-chief granted many of these lands to a second tenant, in return for tax and military service, and they were the immediate lord over the peasants and freemen working the farms. They were often connected to the tenant-in-chief through familial connections or from the same region in Normandy or Brittany as vassals.

At the time of the Domesday survey, the sub-tenants, or vassals of a tenant-in-chief to whom they paid homage and swore fealty, owed military service to their lord for their fiefs which they held ‘freehold’, ie. held for life and was heritable by their heirs. The Norman kings eventually imposed on all freemen who occupied a tenement, a duty of fealty to the crown rather than to their immediate lord who had enfeoffed them, to prevent barons raising their own armies against the king.

The Malets as tenant-in-chief

The most powerful lord in Norfolk and Suffolk with huge land holdings in Domesday Book was named Robert Malet who accompanied the Conqueror with his father William Malet who held substantial property in Normandy with a castle in Graville-Sainte-Honorine (now in Le Havre), as well as lands near Caen. Another relation was Durand Malet who may have been a brother of William, or a second son, brother of Robert.

William Malet’s

mother was an Englishwoman, thought to be the possible daughter of Leofric Earl

of Mercia and Godgifu the supposed sister of Thorold the Sheriff in the time of

Edward the Confessor, and it has been conjectured that Malet’s grandfather was

probably one of the men who accompanied Emma of Normandy to England in 1002 for

her marriage with Aethelred.

William Malet was appointed high sheriff of Yorkshire in the 3rd year of William the Conqueror’s reign. He and his wife, Esilia/Hesilia, and younger children were captured by the invading Danes who slew 3000 Normans when they captured York, and were ransomed. This was followed by the infamous ‘harrying of the north’ resulting in widescale destruction and famine. After William’s release, he was appointed sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk, granted the barony of Eye, building a castle at Eye as his military and administrative headquarters and starting a market. William died c.1171 and his extensive landholdings were inherited by his eldest son Robert who was granted the Honour of Eye, consisting of a widely scattered grouping of manors and land holdings spread over eight counties and was one of the largest estates in England after the Conquest. The bulk of the properties were in Suffolk and Norfolk. Robert’s seat was Eye Castle, where he built and endowed a monastery of Benedictine monks.

In the Domesday

survey of 1086, Robert held, as tenant-in-chief, 34 lordships in Yorkshire, 5

in Essex, 1 in Surrey, 1 in Rutland, 2 in Nottinghamshire, 8 in Lincolnshire,

and 27 in Norfolk and 173 in Suffolk whereof Eye was the

chief.

Most of Malet’s estates in East Anglia had been granted as successor to the pre-1086 lord, Eadric of Laxfield, a wealthy and influential Saxon who was the third largest landholder in Suffolk. The total land area of the Honour of Eye is estimated at least 75,000 acres of which 47,000 were located in Suffolk, making Robert Malet the second largest landholder in Suffolk after the Abbot of Bury St Edmunds.

Robert Malet’s largest land-holding sub-tenants in Suffolk and Norfolk were:

Malet’s mother

Esilia (42 manors); Walter de Caen (31 attributed- 4 as ‘W. de Caen’, and 14+ as just 'Walter'), Walter filius Albrici/fitzAubrey, (11+ possibly some attributed to just ‘Walter’); Humphrey filius

Robert (28); Hubert de MonteCanisy (24 attributed- several just as ‘Hubert’);

William Gulafre (19 attributed- 4 just as ‘William’); Robert de

Glanville (17); Gilbert (17- possibly Robert Malet’s younger brother named

Gilbert, or Gilbert the crossbowman, or Gilbert Blund, or Gilbert de Wissant,

or Gilbert de Coleville); Gilbert Blunt/Blund (10); Walter (10 - see

Walter de Caen where 14 other lands in name of ‘Walter’ attributed to de Caen);

Walter fitzGrip (9); Gilbert de Wissant (6); Loernic (5); Walter

the crossbowman (4 attributed- 2 near Eye just named as ‘Walter’- see

‘Walter’ and Walter de Caen above); Northmann the sheriff (4- also lived in

England pre Conquest); Gilbert de Coleville (4); Fulcred (5) and Robert son of

Fulcred (4); Walter de Risboil (3 - in and near Parham); and 22 other

sub-tenants with less than 3 lands.

One of Malet’s most favoured sub-tenants was Walter de Caen who is said to have come to England with Robert Malet, and it has been suggested by some historians that they may have been related, although unsubstantiated. There is division amongst historians on whether Walter de Caen was also another Domesday tenant named Walter fitzAubrey (further discussion later).

A similar

suggestion is made by some historians that Hubert de MonteCanisy was

possibly related to Robert Malet through marriage. MonteCanisy near Deauville

in Normandy was very near the Malet’s seat at Graville-Ste-Honorine (near Le

Havre). Hubert de MonteCanisy was also a donor and prime witness to Malet’s foundation

charter to Eye Priory, and was appointed seneschal of Eye Priory after Malet’s

death in c.1106, a position inherited by his son of the same name.

Robert Malet’s foundation charter to Eye Priory c.1103-05

Of these sub-tenants of Malet, the following made donations and/or witnessed Robert Malet’s foundation charter to Eye Priory, and all held lands close to Eye Priory:

Robert filius Walter de Caen (witness, indicating that Walter must have been

deceased before 1103); Roger filius Walter de Huntingfield (fitzAubrey (donor and witness); Hubert de MonteCanisy (donor and

1st witness); Humphrey filius Robert; William Gulafre (donor and

witness); Hervey de Glanville (witness) an heir of Robert de Glanville, and a possible son of Randulph de Glanville (donor); Walter fitzGrip; Jordan

of Wilby the heir of Loernic; Fulcred of Peasenhall; and, Walter the crossbowman

(donor and witness).

The Benedictine Priory dedicated to St. Peter in the town of Eye, a cell of the abbey of Bernay in Normandy, was supposedly founded by Robert Malet in the latter period of the reign of the Conqueror, after the Domesday survey in 1086. The new community must have still been in its early stages of development when King William died in 1087. Malet begins his charter: Foundation charter of Robert Malet whereby he announces that, with the assent of his lord king William, for his soul and that of his wife, queen Mathilda, for his own soul and for the souls of his father William Malet, of his mother Hesilia, and of his ancestors and kin, he is constructing a monastery at Eye and installing a community of monks therein.

However, historians

generally accept that the contents and donations therein of his foundation

charter, the original having been lost, is dated c.1103-05 under the reign of

Henry I, as Malet lost the Honour of Eye under the reign of William Rufus,

granted to Roger the Poitevan, and the Honour was not reinstated to Malet until

the succession of Henry I in 1100. Also taking into account the donors and

witnesses to the charter, including the sons of Walter de Caen (who, personally,

is missing from the charter), and Malet’s mother (who is also missing), both

presumed deceased, plus the ages of Walter de Caen’s sons, points to the later

date.

The text of Malet’s charter in the Eye Priory Cartulary dates back to c.1260, and contains the details of Malet’s charter donations from himself and from his sub-tenants and local knights, and the Eye Priory Cartulary includes a large number of confirmation charters in the early to mid-12th century by various monarchs, popes and bishops, including the confirmation of the donation of Peter and Hubert Walter’s land in Fressingfield which was not included in the original charter, but first appeared in the confirmation charter of King Henry I.

(Eye Priory

Cartulary and Charters, 2 vols, ed. Vivien Brown, 1992)

The witness list for Malet’s Charter contains many names of this small area of Suffolk that will become familiar, notably, Hubert de MonteCanisy, Roger filius Walter de Huntingfield (second son of Walter de Caen), Robert filius Walter (eldest son of Walter de Caen), Hervey de Glanville (father of Rannulf de Glanville Chief Justiciar), Walter Arbalestarius (the crossbowman) and William Gulafre:

The donations in

Malet’s charter are divided into two sections.

The first

section: “For their maintenance he confers upon them (viz. the monks at

Eye) and confirms to them from his own lands, churches and tithes the

following”.

He then lists a

large number of churches with their lands and tithes; then a few bequests of tithes

and lands held from him by Norman knights and barons, such as “at the

request of Osbert de Cunteville all the land which he held in Occold; with the

assent of Walter fitzGrip all the land which he had in Fresingfield with

the mill; the tithe of Oyn Compayn of Instead; the grant of Walter

the arblaster (crossbowman) of his tithe of Halegestowe and of Gosewolde

and the church of St Margaret with its land; the tithe of Humphrey of Playford

with the church of that vill with its lands and tithes”;

Followed by: “all the tithes of the following manors of his (Malet’s) demesne: Eye, Stradbroke, Redlington, Dennington, Tannington, Badingham, Kelton, Hollesley, Leiston, Laxfield, Barrowby (Lincs), Sedgebrook (Lincs.), Welbourne (Lincs.), Wakes Colne (Essex), and South Cave (Yorks);

They are to hold

all their possessions free and quit of all exaction and to have soke and sake

and toll and team and infangenetheof in Eye, in Dunwich and in all places where

they have lands, and have all the other liberties which my lord William king of

England granted me when he gave me my honour.”

It is possible

that the first section was part of the original charter made in the time of

King William I, with the original donors listed, including Malet's own personal donations from his Honour of Eye.

Notably, in the succeeding confirmation charters of various monarchs, popes and bishops in the Eye Priory Cartulary, Hubert Walter’s tithe donation is placed in the list of Malet’s ‘manors of his demesne’, between Badingham and Kelton, rather than as a separate donation in the second section of the charter, implying that Hubert Walter’s lands were located in Malet’s own demesne. which raises questions on the basis of this unique entry and why it was included in the first section of the charter, as opposed to the majority of donations in the second section.

Was this to prevent the land being taken from the priory by the reigning monarch at the time, such as King Stephen who did not acknowledge this entry of Hubert's in his confirmation charter?

Also, notably, Wingfield is not included in the above list of Malet's manors, maybe because it was a berewick of Stradbroke in Domesday, and neither is Fressingfield (partly held by Walter fitzGrip) or Chippenhall (which encompassed Fressingfield in Domesday).

While Instead is listed in the charter under the name of ‘Oyn Campayn’ who donated his tithe, nothing more is known of him, and Instead was originally held by William Malet, as part of his fief before his death 1171, later held by his son Robert in Domesday with one freeman (maybe Campayne) commended by the Bishop of Hoxne.

The second section of the charter list of donations begins:

In addition, he grants and confirms the gifts which his barons and knights made to them with his consent, namely, the tithes of: Roger de Huntingfield of Huntingfield, Linstead and Byng (son of Walter fitzAubrey); Richard Hovel of Wyverstone; William Gulafre of Okenhill (son of Roger Gulafre); Oger de Pucher of Bedingfield; Ernald fitzRoger of Whittingham (in Fressingfield) and Hasketon (son of Roger filius Ernald); Ralph Grossus of Creeting St Peter; William de Roville of Glemham and Clakestorp; the tithe of 30 acres in Glemham of the fee of [Alan] the count of Brittany (d.1093); Hugh d’ Aviliers of Brome and Shelfanger; Odo de Charun of Gislingham and Roydon; Godard of Gislingham; Hubert of Rickenhall (de Montecanisy); Randulf de Glanville (of the hospital at Yaxley- possible father, or grandfather of Hervey de Glanville); Hubert de MonteCanisy (of the hospital at Yaxley; with Malet giving the church of Yaxley with all its appurtenances); Robert Malus Nepos of Huntingfield (Huntingfield wholly held by Walter fitzAubrey from Malet in Domesday- a charter witness named Hubert Malus Nepos); Jocelin (Rocelin) of Hollesley (Hollesley held by Robert de Glanville from Malet in Domesday); Geoffrey of Braiseworth; Fulcred of Peasenhall (held by Fulcred in Domesday); and the tithe of Humphrey fitzUnuey.

Many of these named barons and knights were the sons of those named in the Domesday Book, and were living well into the 12th century. This implies that these donations were made after Malet regained the Honour of Eye after the succession of Henry I in 1100.

Malet concludes: to the other men, knights and sokemen of his jurisdiction he grants and commands that they shall make gifts to his monastery of Eye according to their resources. All of these things with the consent of witnesses, Robert Malet has offered to the church of his monks upon the altar of St Peter’s of Eye and has confirmed for ever by this charter.

Robert Malet died c.1106, and although his Honour of Eye reverted back to the Crown until awarded to Stephen Count of Mortain c.1113 (Henry I’s heir), many of his lands in East Anglia were inherited by his sub-tenants’ descendants who continued to live there, on condition of loyalty to the Crown. The close association of many of Malet’s subtenants’ descendants continued throughout the 12th century, as knights and barons of the county of Suffolk and of the Honour of Eye, and some intermarriages to consolidate the lands held by their ancestors.

Durand Malet who shared land with 'Walter'

Durand Malet was thought to be either a brother of William Malet or younger brother of Robert Malet.

There

are several questions relating to a man named Durand, and Durand Malet, and his

possible relationship to the Walter family. However, there were also several entries in Domesday which had just 'Durand' and it is unknown whether any of these were also Durand Malet.

A Walter shared ownership with Durand of 26 acres at Marham in Norfolk in 1070, which was still in Walter’s hands in 1086.

In Domesday, the

lands of Hugh de Montfort (who saved William Malet’s life at the Battle of

Hastings) shows that Walter continued to hold the land of Marham in 1086, but

no longer with Durand:

In Marham,

there are 26 sokemen whom Walter holds. St AEthelthyrth held them TRE in

soke. There were 8 bordars, now 9, Then 5 ploughs, now 4, 6 acres of Meadow.

Then it was worth 80s, afterwards 60s, now 40s. He received this land in

exchange and it has been measured in the return of St Aethelthryth (viz. Ely Abbey, Cambridgeshire).

Was this ‘Walter’ referring to Walter de Caen who held a close relationship with the Malet family, or another Walter? The most likely candidate is Walter de Caen.

Was this the same Durand who held Ickleton from Hardwin de Scales?

Ickleton was the estate of the Walter family inhabited by Hamon Walter, and donated by Hubert, Theobald and Hamon to West Dereham Abbey following Hubert’s foundation charter to the abbey. Notably, the grandson of Hardwin of Scales, Domesday holder of Ickleton, was a witness to Hubert’s Charter. Whether this is relevant is unknown. The estate called ‘Durhams manor’, was assessed at 1 hide, c.1235.

Domesday entry: In Ickleton, Durand holds half a hide from Hardwin (of Scales). There is land for 4 oxen. It is worth 32d; when received 12d. TRE 5s. Eastraed held this under Earl Ǣfgar and he could sell it.

Count

Eustace also held 19 hides at Ickleton which became part of the Honour of

Boulgone, and later held by Roger de Lucy.

It is unknown when the Walter family attained their smaller portion, but the W. Dereham donation indicated the manor was held by younger son Hamon, and another document, outlining a suit ‘about the land of Hervey Walter in the town of Ickleton disputed by the canons of W. Dereham and the convent of Ickleton’ indicates that the land originally belonged to his father Hervey Walter (possibly in his marriage settlement with the Valoines family).(Papal Judges delegate in the Province of Canterbury 1198-1254: A Study in the Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction and Administration’ by Jane E. Sayers, Oxford Uni Press, 1971. p.xxv)

Was this ‘Durand’

named in the Domesday entries for Marham and Ickleton, also Durand Malet?

'Durand Malet’ held, as tenant-in-chief in 1086, 22 lands in Lincolnshire, 3 in Leicestershire and 1 in Nottinghampshire’.

Cyril Hart, ‘William Malet and his Family’ (Anglo-Norman Studies XIX: Proceedings of the Battle Conference, 1996, p.145):

Hart speculated on whether Durand Malet, either Robert Malet’s brother

or uncle, was the same Durand who held, as an undertenant, seven lands in

Cambridgeshire, as well as a couple of lands in Norfolk and one in Suffolk (viz.

Cransford held by Robert Malet).

‘The Durand who in 1072-5 shared ownership with one Walter (as undertenants

of Hugh II de Montfort-sur-Risle, the Conqueror’s constable) of 26 sokemen on

26 acres at Marham on the edge of the Norfolk marshland may have been the same

person as the Durand who held a number of estates in Cambridgeshire in 1086 as

an undertenant of Hardwin de Scales, a despoiler of Ely, including half a hide

at Ickleton*.

Hart also stated that, ‘this holding at Marham had

been seized by Hugh from Ely after the fenland uprising of 1070-1’ (during

which William Malet was killed). It is not impossible that Durand was given

all these under-tenancies after the mission of William Malet which followed the

uprising. For two different Durands to be holding estates in the eastern

counties would be a most odd coincidence. A pedigree constructed a century ago

by the Malet family places Durand Malet as William’s brother. This is

plausible, but unsupported by conclusive evidence.

C.P. Lewis wrote in his ‘The King and Eye: a study in Anglo-Norman politics’, (The English Historical Review No. CCCCXII- July 1989, Oxford Univ. Press) pp.577-580, 588:

The manor of Wellingore (Lincs.) was represented in Domesday Book either by a royal manor, or by a berewick belonging to Durand Malet, or perhaps by both Domesday estates combined. Durand's kinship with Robert Malet of Eye is strongly suggested by the facts that their Nottinghamshire manors were listed consecutively in Domesday Book and that a Durand had taken illegal possession of Robert Malet's only manor in Surrey. Most of Lancashire north of the Ribble became Robert Malet’s only after the date of Domesday Book, while among the churches which he gave to the Norman abbey of Sees when he founded Lancaster Priory in I094 was a Boothby which was presumably Boothby Graffoe (Lincs.), a royal manor in 1086, and Navenby (Lincs.), a Domesday manor of Durand Malet. It looks as if, whatever disgrace had brought down Robert Malet, had also involved his kinsman Durand, and that the king gave their lands together with some of his own to Roger the Poitevin.

Prof. Katherine Keats Rohan suggested that the links between Durand’s land and those of Alfred of Lincoln (related by marriage) indicates that Durand was probably a younger brother of Robert Malet. (‘Domesday Book and the Malets’ 1996, printed in Nottingham Medieval Studies 41)

It is unknown whether this information on Durand Malet has any relevance to this quest.

N.B. FOR THE SAME REASONS OF LACK OF EVIDENTIAL DOCUMENTATION, THE SUGGESTIONS OF ANCESTRY IN THIS ARTICLE CAN ONLY BE SPECULATIVE.

ANCESTRAL CANDIDATES NAMED ‘WALTER’ IN Co. SUFFOLK IN DOMESDAY

In several entries, once the full name

was used for one entry, the successive entries in the same ‘Hundred’ of a

county, held by the same person, often only used the first name without

repeating the appellation, some entries saying “the same Walter holds”. This

became confusing when there were several Walters holding land in the same or

adjacent areas.

Looking at the lands in Suffolk held by the Walter family, namely parts of Wingfield, Instead/Weybread, ‘Sikibro’ (unidentified but possibly Stradbroke/Stetebroc), and the manor of Snapeshall a part of Fressingfield, all in the Hundred* of Bishops or Hoxne, there were several Normans named Walter who could be candidates for the origin of the ‘Walter’ surname, who held lands in this area in the Domesday book as sub-tenants of Robert Malet- Walter de Caen, Walter filius Aubrey, Walter the crossbowman, Walter fitzGrip, possibly Walter de Glanville, and a man just named ‘Walter’. We will look at these Walters to try and determine which could be the most likely forebear of this family.

* Hundred=

a division of an English shire for administrative, military and judicial

purposes under the common law, consisting of 100 hides/enough land to sustain

approximately 100 households.

Map of Hundreds of Suffolk, showing Hundreds of

Hoxne/Bishop’s and Hartismere

Within the short distance of about 20 kms from Eye to Huntingfield, in this northern area of Suffolk bordering Norfolk, these five sub-tenants of Robert Malet named ‘Walter’, held land in the Domesday Book including the lands later held by the Walter family. Sorting which of these Walter’s could be the ancestor of the Walter family is the difficulty.

*a plough team= area of land needed for an 8-oxen

plough team to work it; often called a ‘carucate’ of land, thought to be about

120 acres.

Instead is a

small hamlet or manor containing a mill near the river Waverney, which is

considered to be part of Weybread.

Domesday Book: ‘In

Instead, 1 free man with 10 ½ acres and the fourth part of a mill. It is

worth 2s. William Malet held this; afterwards Robert his son held it, thinking

it belonged to his father’s fief’.

1.WALTER

WHO ‘HELD OF THIS MANOR’

The first possible, and most likely candidate is the sub-tenant holding lands from tenant-in-chief Robert Malet in the Domesday Book, just named ‘Walter’ and in several entries as ‘Walter who held from this manor’, who also held all of the lands that subsequently were held by Hervey Walter and Peter Walter in this same area of Suffolk- viz. the Wingfield fee held by Hervey Walter, Weybread/Instead mill held by Hervey Walter and Theobald and Peter Walter, as well as part of Fressingfield held by Hubert Walter (the elder) and his son Peter Walter, and Stradbroke, adjacent to Wingfield, which is possibly the unidentified ‘Sikebro’ in Hervey Walter’s Butley charter, all situated in the Hundred of Bishop or Hoxne in northern Suffolk.

The entries for these lands in the Domesday Book need to be explored in detail to see how Walter is connected.

Butler historian Theobald Blake Butler also identified ‘Sikebro’ as Stradbroke in his ‘Origins of the Butlers of Ireland’ article, but this conclusion is unproven. (Theobald Blake Butler, ‘The Origin of the Butlers of Ireland’, The Irish Genealogist, v.1. No.5, April 1939, pp.147-157)

In the Domesday Book, Wingfield is listed as a ‘berewick’ of Stradbroke in Malet’s list of lands. berewick [als. ‘barton’] defined as a detached portion of farmland that belonged to a medieval manor, reserved for the lord’s own use, often a monastic institution or other major landowner.)

Stradbroke possibly also Sedgebrook ‘Sechebroc’ in Lincolnshire, held by Robert Malet in Domesday, but unlikely. It is also possible ‘Sikebro’ (‘bro’ a contraction of brook) was the name of a small manor in the same area of Wingfield, like Peter Walter’s ‘Snapeshall’ was a manor in Fressingfield.

Map of the Hundred

of Bishop (Hoxne Bishops), and neighbouring Hundred of Hartismere to the west,

centred around Eye.

(The Norfolk border partly follows the Waverney River between Mendham, Needham to Diss)

‘Domesday Book: A Complete Translation’, eds. Dr Ann Williams, Prof. G.H. Martin, 1992, 2002, pp.1219-20 (TRE means value pre-Conquest 1066):

The Domesday

Book entries for this small area of Suffolk known as the Hundred of Bishop:

ie. Laxfield,

Badingham, Bedfield, Stradbroke and berewick of Wingfield, Horham (1st),

Wilby, Chippenhall (ie. including lands of Fressingfield), Weybread (x3

entries), Horham (2nd), Chickering, Bedingfield.

Of the above lands held by Malet in the Hundred of Bishop's or Hoxne:

Laxfield consisted of 6 carucates of land and 80 acres, worth £8 (TRE=£15).

Stradbroke/Wingfield

consisted of 5 ½ carucates of land worth £16 (TRE=£14)

Badingham held

9 carucates of land, worth £10 (TRE=£15)

Chippenhall held 2 ½ carucates of land worth £6 (TRE=100s)

Weybread held, in three parcels: 2 carucates + 6acs meadow + 2.8 mills, ½ a church, worth £4.11s.2p. (TRE £1.10s.); 72 acres + 4 acs meadow + 1 mill, worth £1.10s (TRE £1.5s.); 90 acs + 4ac meadow, 1 mill, worth £1.5s. (TRE 15s.)

All of the other

lands named were much smaller and valued well below £1

All of these lands were held by six sub-tenants of Malet: Walter, Walter filius Grip, Robert de Glanville, Humphrey filius Robert, Loernic, and Malet’s mother Esilia

(It should be noted that, while Robert Malet was by far the largest land holding tenant-in-chief in this area, there were other tenants-in-chief who also held some lands in this area apart from Malet- ie. Roger de Poitou, the Abbey of Bury St Edmunds, Bishop William of Thetford, Hervey de Bourges, and King William.)

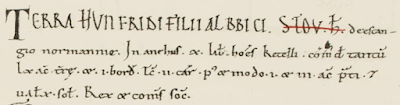

Original pages in the Domesday Little Book: Suffolk- Robert Malet's Lands-

Bishop’s Hundred, beginning with Laxfelda/Laxfield and

Badincha/Badingham[1];

Stradbroke/Stetebroc and Winebga/Wingfield near bottom of 1st page.

Cibbehala/Chippenhall end of 2nd page

NB. several held by ‘Walter or Galter de hoc manerio’/of this manor:

[1]

Domesday Book, or the Great Survey of England of William the Conqueror, AD

1086, Suffolk, Col. Sir H. James Director, 1868, pp.xccvi-xcix

Translation pages:

Summary of lands

held by ‘Walter’ in Bishops Hundred, co. Suffolk (Parish of

Hoxne) from tenant-in-chief Robert Malet in ‘Little Domesday:

Lands of Robert Malet’ in 1086

Terms:

TRE= Tempore

Regis Edwardi- in the time of King Edward; pre-Conquest 1066)

Sokeman: A sokeman belonged

to a class of tenants found chiefly in the eastern counties, especially the

Danelaw, occupying an intermediate position between the free tenants and

the bond tenants in that they owned and paid taxes on their land

themselves. Forming between 30% and 50% of the countryside, they could buy

and sell their land, but owed service to their lord's soke, court,

or jurisdiction

Villan: a

peasant of higher economic status than a Bordar and living in a village.

Notionally unfree because subject to the manorial court.

Bordar: a

cottager; a peasant of lower economic status than a villan

Carucate of land-

notional area of land able to be farmed in a year by a team of 8 oxen pulling a

carruca plough, usually reckoned at about 120 acres.

Acre- an

amount of land tillable by one man behind one ox in one day. Traditional acres

were long and narrow due to the difficulty in turning the plough.

A Hide-

amount of land needed to support one peasant family; In 12-13th

centuries, the hide commonly appeared as 120 acres of arable land, but was in

fact a measure of value and tax assessment.

A Hundred- a

sub-division of the shire or county used for administrative purposes (larger

than a parish), each having its own representative body from local villages.

Nominally 100 hides to sustain approximately 100 households, but in practice

the size of a Hundred varied widely from place to place.

Antecessor of Robert Malet pre-Conquest (TRE) was Eadric of Laxfield (ie. predecessor or previous landholder from whom the 1086 holder might claim legal title):

1)Badingham- Walter holds of this manor 100 acres, 2 villans and 6 bordars, worth 30s.

(also,

Loernic 40 acs.; Robert [? de Glanville] 40 acs)

2) Laxfield- Walter holds of this manor, 3 villans with 50 acres worth 20s.

(also, Loernic

40 acs. Worth 10s.)

NB. In his

charter to Eye Priory, Robert Malet donated the church of Badingham and all its

lands and tithes and one carucate of land in that vill, and the church of

Laxfield with all its lands and tithes, and his demesne manors of Badingham and

Laxfield to the monks of Eye Priory.

3) Stradbroke and it’s berewick Wingfield- Walter holds from this manor 2 sokemen with 40 acres worth 8s.

(also Robert de

Glanville held 4 sokemen with 20acs worth 5s; Walter fitzGrip held 1 sokeman

with 15 acs. worth 30d.; Loernic 1 sokeman with 20 acs worth 3s)

Notably the original has a later inclusion, by the same cleric, in the section on Stradbroke/Stetebroc: ‘And Wingfield [‘Winebga’] to wit a berewick in the same account and valuation’, (berewick= an outlying estate)

4) Chippenhall (includes the land of Fressingfield)- Of this manor Walter holds 4 sokemen with 1 carucate of land (about 120 acres) worth 30s.

(also,

Humphrey 1 sokeman with 20 acres worth 5s; Walter fitzGrip 1 freeman, 120 acs.

worth 40s; Malet’s mother 3 sokemen and 80 acs worth 45s.)

5) Weybread- Humphrey [filius Robert] holds 5 sokemen and Walter 1 sokeman worth 10s; 72 acres and 5 bordars, 1 plough and 4 ½ acres of meadow; woodland for 14 pigs. Then as now 1 mill. It is worth 17s. (NB. This was only one parcel of land of three held by Humphrey in Weybread- see below)

Instead- In

Instead, 1 freeman, over whom Bishop Ǣthelmar had the commendation TRE, with 10

½ acres and the fourth part of a mill. 1 bordar. Then half a plough, now 2

oxen. It is worth 2s. William Malet held this; afterwards Robert his son [held

it], thinking it belonged to his father’s fief. (Evidence at the Great Inquest of 1086 was given by the Freemen in the King's hand about who held Instead TRE- "Domesday book and the Law", by Robin Fleming, 1998, p.434, Case No. 3195: Instead)

Humphrey also

held another large part of Weybread from Malet- In Weybread, 1

freeman with 2 carucates of land which Humphrey holds as a manor with 10

bordars. I freeman holds 20 acres- the same Humphrey holds this. In the same

vill, Humphrey holds 3 freemen with 91 acres and 17 bordars, one mill and 3

parts of another, etc. Worth 40s.

Humphrey filius

Robert

The sub-tenant

named Walter shared lands of Robert Malet in Weybread and

Chippenhall/Fressingfield with Humphrey filius Robert, one of Malet’s

largest sub-tenants in Domesday. Humphrey also held Mendham (and his

descendants held Withersdale [not included in Domesday], between Mendham and

Weybread).

Looking at the

map above, it appears that Humphrey and his heirs held the lands east of ‘Weybread

Street’ (joining Weybread to Fressingfield)- ie. Weybread to Mendham, Withersdale to Chippenhall/Fressingfield,

while ‘Walter’, and subsequently the ‘Walter’ family, held the lands west of

this same ‘Weybread Street’- ie. Stradbroke to Wingfield, to part of Fressingfield

(known as Snapeshall manor, just north of Fressingfield), to Instead/Weybread.

Humphrey’s ancestry is unknown, nor his obviously close relationship to the Malets. He held Playford from Malet in Domesday and the tithes of Playford and the church of that vill were donated to Eye Priory in Malet’s Charter to Eye in c.1103-05, which his two sons confirmed, so it would appear that Humphrey was deceased before then. And there appears to have been an ongoing relationship between Humphrey’s descendants and the ‘Walter’ family and the de Glanville family.

Humphrey’s sons

were his eldest Adelm who died without issue before 1125, his fees inherited by

his brothers Fulcher of Playford, and Peter of Playford whose son was Hervei

filius Peter of Playford.

According to

Vivien Brown (Eye Cart, II, p.75), apart from two small holdings, all of

Humphrey filius Robert’s Suffolk manors including Playford, parts of

Fressingfield, Weybread, and Withersdale, were held by Alan II of

Withersdale (d.bef.1241), in the early 13th century. Alan II,

son of William of Withersdale (d.1194-1200), son of Alan I (d.1184) who

inherited ten fees of Fulcher (relationship not clear) son of Humphrey filius

Robert. Alan I is known from a plea in 1194 between his son William and Hervey

filius Peter, wherein William stated that his father Alan had pledged land in

Playford to Hervey (Rolls of King’s Court 1194-5, 50). Alan I is also

mentioned in a fine of 1213 in which Alan II disputed the advowson of Weybread

church with the prior of Butley (Feet of Fines, No. 556). Alan I of

Withersdale is recorded, along with Gutha de Glanville (sister of Rannulf;

children of Hervey de Glanville), as having donated the church of Weybread, as

found in the 14th Century Rent Roll of Butley Priory (East

Anglian: Notes and Queries... counties of Suffolk, Cambridge, Essex &

Norfolk, v.11, Jan 1906, ed. C.H. Evelyn-White, p.46: An Unpublished

Fourteenth-Century rent Roll of the Priory of Butley, Suffolk):

The rent of half

a mark in the town of Playford was the gift of Hervey filius Peter of Playford

to Hubert Walter’s foundation charter to West Dereham Abbey. (His

gift statement in the charter mentioned the homage of Alan son of Thurstan with

his whole tenement which he held of Hervey in Playford- whether this is the

same Alan is unclear.) (Monasticon Anglicanum, ed. Wm Dugdale, 1846,

v.6ii, Abbey of West Dereham, Charter No.II, p.900)

Peter Walter was

custodian of Alan II de Withersdale during his

minority after father William’s death c.1195-1200, until his majority before

1204, as stated by Alan in a record of an assize of ‘darrein presentment’

to the church of Playford, the advowson of which the prior of Eye claimed

against the bishop of Norwich and Alan of Withersdale dated 1227. (Eye Cart.

II, p.117, No.391)

Withersdale is

adjacent to Weybread and just north of Fressingfield, and was not listed in

Domesday.

(See Eye Cart.,

Charter Nos. 346 and 347, re. Adelm and Fulcher and his witness Roger de

Glanville; Eye Cart II, p.75 re Playford; p.117 No.391; Three Rolls

of the Kings Court in reign of Richard I, A.D.1194-95, p.50 re Alan and

William of Withersdale and Playford)

Peter Walter was also connected with another two of Malet’s larger sub-tenants in Bishops Hundred and both donors and witnesses to Malet’s Eye charter-firstly, William Gulafre of Okenhill in Badingham, whose son Roger Gulafre of Okenhill was sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk. In 1200, Peter Walter bargained with the king on behalf of his son Hubert, for the marriage of Philippa Gulafre (widow of Robert Brito) who was daughter of William, son of Roger Gulafre (son of William Gulafre), for which Peter promised to pay 60 marks, although the sum of 120 marks and a palfrey were ultimately given for the marriage. (Rotuli de oblatis et finibus in turri Londinensi asservali, tempore Regis Johaniis, 1835 pp.42, 70; V. Brown, Eye Cartulary II, pp.58-60)

In Domesday,

William Gulafre often shared lands with Walter de Caen as subtenants of Malet.

And secondly,

Peter Walter was close to Roger II de Huntingfield son of William de

Huntingfield, son of Roger I de Huntingfield. Peter’s relationship with this family will be explored in detail, below,

in the section of Walter filius Aubrey.

Also notable is that Loernic also held lands in Laxfield, Badingham and Wingfield/Stradbroke, as well as neighbouring Wilby where ‘Loernic held 20 acres which Aelfric had held TRE’. Loernic’s successor Jordan granted his tithes of Wilby to Malet’s charter. The name ‘Loernic’ is not Norman in origin, but Anglo-Saxon, as was ‘Eadric’, indicating that Loernic probably lived in this area pre-Conquest and held some status maybe as the son of a Saxon lord. Notably, Robert Malet’s father William Malet’s mother was Anglo-Saxon, but whether there is a connection is unknown.

EYE in the Hundred of Hartismere (adjacent to the Hundred of Bishop)

Robert Malet held the Honour of Eye, with his seat and administrative centre at Eye Castle, where he also built and endowed a monastery of Benedictine monks. His father William had built the castle and granted the barony of Eye by King William, who then granted Robert the Honour of Eye on his father’s death.

The Domesday

Book entry on Eye states that Robert Malet holds it in demesne. A demesne is

described as “all the land retained and managed by the lord of the manor

under the feudal system for his own use, occupation or support”.

A small select number of knights and close associates of

Malet were granted lands from his demesne lands viz. Malet’s mother Esilia,

Walter, Walter the crossbowman, Walter de Caen and Herbert were the only people

so honoured, which is probably an indication of their clsoe relationship to Malet.

(As there are no

records of a ‘Herbert’ in Suffolk, presumably it refers to Hubert, the first

prior of Eye Priory in the time of William the Conqueror and Henry I)

Domesday:

Eye (in the

Hundred of Hartismere, adjacent to Bishops Hundred)- Lands of

Robert Malet:

Eadric held Eye

with 12 carucates of land TRE; now Robert Malet holds it in demesne, and his

mother holds 100 acres, worth £21 (TRE= £15)

To this manor

belong 48 sokemen with 121 acres of land. Of these sokemen 37 are in demesne.

Herbert holds 9 with 20 acres and Walter 1 with 5 acres and Walter the

crossbowman 1 with 16 acres. All this is worth 9s. Then 4 ploughs, now 3,

and 1 acres of meadow. Then it was worth £15, now £21. Eadric had soke and sake

of the bishopric. There belong also to this manor 9 free men with 110 acres of

land in the soke and commendation of Eadric TRE (names 9 Saxon free men).

In the same vill

1 freeman, Wulfric commended to Eadric (of Laxfield, TRE) held 30 acres as one

manor TRE; now Walter de Caen holds it from Robert (Malet). Then as now

2 bordars, worth 20s.etc

(ref: Domesday

Book: A Complete Translation, pp. 1213, 1219-1220)

Comment: The entry for Eye specifically named the ‘Walter who held 1 [sokeman] with 5 acres’ and ‘Walter the crossbowman who held 1 [sokeman] with 16 acres’. The difficulty is identifying the man named ‘Walter’. The wording clearly makes a distinction between ‘Walter’ and Walter the crossbowman. It could refer to Walter de Caen, however, it is odd that he should just be named Walter in this paragraph, then given the full name Walter de Caen in the following paragraph. It could also be Walter fitzAubrey as he is named in the preceding paragraph for the lands of Loudham (although in a different Hundred viz. of Wilford), and this seems to be the most logical choice.

It would appear to suggest that there were three knights named Walter granted lands out of Malet’s demesne of Eye, and the fact they were the only ones to be granted lands out of the Malet's seat of Eye, suggests a very close relationship between the Malets and these particular sub-tenants who all held lands close to Eye.

The question is

whether the Walter who held 5 acres at Eye was the same Walter who held lands

in Stradbroke and its berewick of Wingfield, Weybread, Chippenhall (Fressingfield),

Laxfield and Badingham, or/and whether it was referring to Walter de Caen or Walter filius Aubrey.

In his Charter to Eye Priory, Robert Malet donated the church of Eye with all its lands and tithes, and the tithe of the market of Eye, and part of his 'burgage in Eye with one fishpond'.

Domesday Book entry for EYE:

'WALTER WHO HELD OF THIS MANOR'

The point that

is most noticeable in the Domesday entries on Bishops Hundred is the uniqueness

of the entries pertaining to this ‘Walter’ who is the only sub-tenant in the

Domesday book who is described as ‘holding of this manor’ in several

lands in Bishops Hundred. According to the Domesday Book, in the entry for

Chippenhall (including Fressingfield), lands of Robert Malet, “the soke [of

these lands] is in Hoxne, but Eadric [of Laxfield] held half from Bishop

Aelmar. Of this manor Walter holds 4 freemen with 1 carucate of land,

worth 30s. and it is in the same valuation of £6.”

Similar wording

appears for Wingfield/Stradbroke- ‘Of these, the soke and sake is in Hoxne,

the bishop’s manor and Eadric held half from the bishop. Then it was worth £14,

now £16. Walter holds from this manor 2 sokemen with 40 acres worth 8s

in the same valuation, etc.”

Similarly, with

the wording for the lands in Laxfield and Badingham. While there are several

other lords holding lands from Robert Malet in these same lands, ‘Walter’ is

listed firstly, and as he is listed under the lands held by Robert Malet not

Bishop William of Thetford who held the manor of Hoxne (predecessor Bishop Ǣlmar)

in Domesday, the lands of the manor must refer to the half portion held by

Eadric of Laxfield from the Bishop, which in turn became Robert Malet’s and

became part of his demesne attached to Eye.

On what basis Walter held this particular group of lands from the manor and from Robert Malet’s demesne lands, is the mystery. It may explain why the cartulary entry for Hubert Walter (the elder) who donated his tithes of his manor of Snapeshall in Fressingfield to Eye Priory, was placed in amongst the list of Malet’s ‘manors of his demesne’ which he personally donated to the Priory, rather than a separate entry of a donation as with all other contributors.

The manor of Hoxne was a residential episcopal manor, the seat of the bishopric at the time of the Confessor, and Bishop Ǣlmar held 9 carucates of land in Hoxne Bishops in 1066. This was granted to Bishop William of Thetford in 1086, and, as stated, Eadric held half of the manor’s lands from Bishop Ǣlmar, which was then granted to Malet.

The following example shows how the land portions of the different sub-tenants’ of Malet were expressed in the Little Domesday Book entry, ‘Lands of Robert Malet’, and in each case, Walter is named firstly:

In Chippenhall, 9

free men by commendation [held] 2 ½ carucates of land. Then as now 17 bordars.

And 10 ploughs and 12 acres of meadow. Woodland for 300 pigs. Then it was worth

100s., now £6. Half a church with 20 acres and 1 plough. It is 2 leagues long

and 1 broad. 15d in geld. The soke is in Hoxne [manor], but Eadric held half

from Bishop Ǣlmar. Of this manor Walter holds 4 [freemen] with 1

carucate of land [It is worth] 30s. and it is in the same valuation of £6.

The mother of Robert Malet [holds] 3 [freemen] with 80 acres [worth] 45s.

in the same valuation. Humphrey [holds] 1 [freeman] with 20 acres. It is

worth 5s. in the same valuation. Walter fitzGrip [holds] 1 free man, 120

acres and it is worth 40s. in the same valuation.

Similarly:

Eadric held

Stradbroke pre-Conquest [TRE] with 5 ½ acres of land. And Wingfield to

wit a berewick in the same account and valuation. Then and afterwards 10

villans, now 11. Then 11 bordars now 30. Then 11 ploughs in demesne, afterwards

6 now 5. Then and afterwards 12 ploughs belonging to the men, now 5. Altogether

20 acres of meadow. Woodland for 400 pigs. Then 3 horses. Then 16 pigs, now 30

and 30 sheep. 2 churches with 40 acres and half a plough. 17 sokemen with 1

carucate of land and 3 ploughs. Woodland for 40 pigs. 5 acres of meadow. Of

these, the soke and sake is in Hoxne, the bishop’s manor, and Eadric

held half from the bishop. Then it was worth £14 now £16. Walter holds

from this manor 2 sokemen with 40 acres. worth 8s. in the same valuation. Robert

de Glanville [holds] 4 [sokemen] with 20 acres [worth] 5s. in the same

valuation. Walter fitzGrip [holds] 1 with 15 acres [worth] 30d. in the

same valuation. Loernic 1 with 20 acres worth 3s. in the same valuation.

Eadric had the soke and sake. It is 2 leagues long and 1 leagues broad.

14 1/2d. in geld. Others hold [land] there.

Terms:

Demesne- all the land retained by a lord of the manor for his own use and occupation, or management.

Soke and Sake- used to denote the judicial and dominical rights associated with the possession of land. Right of jurisdiction enjoyed by a Lord over specified places and personnel.

Domesday:

Laxfield and Badingham- Lands of Robert Malet

Eadric held

Laxfield with 6 carucates of land and 80 acres. etc… Then it

was worth £15, now £8. It is 1½ leagues long and 1 league broad. 6½ d. in geld.

Walter holds of this manor 3 villans with 50 acres. It is worth 20s. in the

same valuation. Loernic holds 40 acres worth 10s. in the same

valuation.

The same

Eadric held Badingham with 9 carucates of land etc…. Then it was worth £15

now £10. It is 1 league and 6 furlongs long and 1 league broad. 10d. in geld. Walter

holds of this manor 100 acres and 2 villans and 6 bordars, worth 30s. It is in

the same valuation of £10. Loernic holds 40 acres in the same

valuation. Robert holds 40 acres in the same valuation. Eadric had

the soke and sake.

The two lands of Laxfield and Badingham belonged to Eadric of Laxfield TRE, and subsequently, his successor Robert Malet, not the bishops of Hoxne. Once again, Walter ‘held of this manor’, and it would appear that in this case, it refers to Eadric’s manor, as Eadric had the soke and sake of both lands, and Laxfield was the demesne manor of Eadric pre-Conquest.

The fact that

Walter was the first listed in each entry, and that he ‘held of the manor’

in each case, would seem to indicate that he either had some prior association

with Eadric of Laxfield, or, with Robert Malet or his father William Malet, who

were granted all of Eadric’s properties, as Malet appears to have shown

particular favour to this Walter and enfeoffed large parcels of Eadric’s

demesne lands to him.

The lands held by this Walter from Malet, at Laxfield and Badingham, were granted to Eye Priory by Malet as part of his list of demesne manors, implying the holder was then deceased and the lands returned to Malet's sole ownership. (Part of Badingham: Okenhall Manor held by William Gulafre from Malet; and the manor of Coleston held by Hervey de Bourges as well as part of Chippenhall as tenant-in-chief.)

Notably, this original list of Malet’s demesne manors in his charter did not include Wingfield or Weybread, or Snapeshall in Fressingfield, but did include Stradbroke:

Malet’s Charter to Eye Priory:

Translation:

(Eye Priory Cartulary and Charters, i, p.13 ed V. Browne)

However, the

later Eye Priory confirmation charters of various monarchs, popes and bishops,

place Hubert’s tithe donation of his land in Snapeshall in Fressingfield in

this same list of Malet’s manors of his demesne.

Eg. Charter of

Pope Alexander III in 1168 (no.56, p.60):

And, Charter of

Henry I, c.1123-1134 (no.3, p.18)

Of all of

Malet’s list of donors to his charter, the placement of this particular entry,

albeit in later confirmation charters, is unique.

EADRIC OF LAXFIELD

An article abut Eadric of Laxfield written by Andrew Wareham:

In Suffolk all

of the estates which were under the personal management of Eadric of Laxfield

in the lordship of Eye, valued at £198 pre-Conquest, became the demesne manors

held by the Malet family (viz. William, his wife Hesilia, and son Robert). In

Norfolk, the Malet family only retained one third of Eadric’s estates. Around

four fifths of the honor of Eye had descended from Eadric of Laxfield, while

around a quarter of his estates passed to lords other than the Malet family. The

consequence of these descents was that the honour of Eye was more closely

focused upon Suffolk than the lordship of Eye had been.

(Lords and

Communities in Early Medieval East Anglia, by Andrew Wareham, Institute of

Historical Research, Chapter: The Formation of Lordships and Economic

Transformations, p.105)

The author of ‘Domesday Book and the Law’, Robin Fleming (p.81) wrote:

William Malet

had been the beneficiary of some early celebrity forfeitures- the most

important of which was his succession in East Anglia to the lands of Eadric of

Laxfield, one of the richest men and greatest lords in the Confessor’s England.

Eadric/Edric of Laxfield is thought by some researchers, to have been the falconer to King Edward the Confessor, and a thane/thegn or nobleman of the first rank. There are several Edrics named in the Domesday Book, including ‘Edric the falconer’ who held part of Shelfanger, and several other lands nearby in the Hundred of Diss near the Suffolk border, pre-Conquest, and in 1086 as tenant-in-chief of Shelfanger (other parts held by King William, Bury St Edmunds, and Count Alan of Brittany, sub-tenanted in Shelfanger by Hervey de Ispania/ Epaignes/Espaine [in Normandy, dept. Eure, who also held several lands of Count Alan in Essex]).(Domesday A Complete Translation p.1178-9). Whether this is the same man is debatable.

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, by Ann Williams (2004) on ‘Eadric of Laxfield’:

Eadric’s name

is one of the commonest in 11th century England, and only where Little

Domesday gives him the distinctive toponymic from his estate at Laxfield, or

refers to him as the antecessor of Robert Malet, can he be securely identified.

All that is known of him comes from Little Domesday Book, the return of the

Domesday commissioners for the East Anglian circuit, which reveals that he had

held some 123 carucates of land in Suffolk and Norfolk. He had also attracted

the commendation of large numbers of lesser thegns and free men (a minimum of

82 named individuals can be identified).

Little

Domesday also records the outlawry of Eadric at some time in Edward the

Confessor’s reign, though the reason is unspecified. His lands were confiscated

by the king and his men sought other lords. When he was subsequently pardoned

and reinstated, Edward issued a writ and seal permitting Eadric’s men to return

to their allegiance, if their lord wished it. This was the cause of several

disputes after 1066, when Eadric’s lands were redistributed among the incoming

Normans.

Anglo-Norman Studies XIX: Proceedings of the Battle Conference, 1996, edited by Christopher Harper-Bill:

William Malet

was given a huge fief in Suffolk, Norfolk and Essex. It was by far the largest

to be granted out by the Conqueror in East Anglia, and the most concentrated of

all the Norman fiefs in England. How was room made for him? Was Eadric of

Laxfield, his antecessor, who must have been of the greatest landholders in

England towards the end of the Confessor’s reign, deprived by the Conqueror of

his vast East Anglian holdings in order that William Malet could be endowed

with them, or did Eadric die conveniently without heirs, just at the right

moment?

Several historians, including Blomefield (History of Norfolk, 1810, v.10, p.433), Augustine Page (History of Suffolk, p.180) and Richard Rawlinson (MS Oxon Bod. Library 78-80), all suggested that Walter de Caen was married to the daughter of Eadric of Laxfield, on what basis is unknown, as there are no records to confirm this theory, Augustine Page describing Walter de Cademo’s grandson William’s donation to Sibton Priory of ‘Friers manor at Shelfanger, formerly the possession of Edric the falconer, his great grandsire, with which Robert Lord Malet, enfeoffed his brother Walter de Cademo.’.

As stated, it is unknown how these historians arrived at this theory of

marriage, but, if there is some unidentified evidence, one could also make the

suggestion that the same theory could apply to the subtenant named ‘Walter’ who

seemed to have a close association with the lands of the demesne of Eadric of

Laxfield in this Hundred of Bishop, several held by Eadric from the Bishop of

Hoxne, subsequently granted to the Malets post-Conquest, with Walter holding

his lands ‘of this manor’, maybe due to a marriage to Eadric’s daughter

(speculation only).

THE IDENTITY OF 'WALTER'

Walter could be an individual who just held the singular name of Walter, one of numerous knights named as such in the Domesday Book.

Walter could be Walter fitzAubrey who held Huntingfield and Linstead in Domesday, a short distance east of Laxfield and Chippenhall. Some historians have concluded that Walter de Caen and Walter fitzAubrey were the same man, although disputed by others due to lack of evidence, however, as they both appear with entries on the same pages of the Domesday Book, it would seem unlikely they were the same man. This will be discussed in detail later.

There is also a suit in 1202 in the ‘Feet of Fines for Suffolk’, in which two descendants of Walter fitzAubrey argue ownership of 300 acres of Wingfield held through ‘recognitio de morte antecessoris’, ie. ‘in recognition of the death of an ancestor’, which suggests that Walter fitzAubrey may have been the ’Walter’ who held part of the manor of Wingfield, a berewick of Stradbroke. (Feet of Fines for the County of Suffolk for the reign of King John 1199-1214, ed. Barbara Dodwell, 1958 p.155, No.311)

Theobald Blake Butler suggested this ‘Walter’ could also be Walter de Caen who held numerous lands as sub-tenant of tenant-in-chief Robert Malet, including lands surrounding those held by the Walters. At neighbouring Horham, Walter de Caen held 3 freemen by commendation with 60 acres and 2 bordars, worth 12s. He also held lands at Eye, and Sibton (east of Laxfield and south of Huntingfield), and several manors just over the border in Norfolk, inherited by his son and heir Robert fitzWalter.

Theobald Blake

Butler initially thought that this ‘Walter’ was the most likely candidate as

ancestor of the Walter family, and he later came to hold the view that the

‘Walter’ who held these lands was probably Walter de Caen, but it is not certain that he knew of the other candidates.

Just north of

the border with Norfolk, at Thelveton, Burston, Semere and Roydon which

were held by Robert Malet, his subtenant was named as ‘Walter’, which

have been attributed to Walter de Caen by Domesday historians.

Diss

Half Hundred- Robert Malet:

In

Roydon, [near Diss] 1 freeman of Eadric’s by commendation held 20 acres; now

Walter holds them.

In Thelveton, there are 2 free men of the same by commendation with 8 acres of land; and Walter holds them.

The argument against this theory of Walter's identity as Walter de Caen, in relation to the Walter family ancestor, is that Hervey Walter held close ties with the extended de Glanville family and his wife’s de Valoines family, as shown in the witness list to his charter to Butley Priory, yet there was no association with the descendants of Walter de Caen, as would be expected if they were closely related, and who one would expect to have witnessed Hervey’s Charter to Butley, if they were close relations. However, in contrast, Robert fitzRoscelin of Linstead, a probable descendant of Walter fitzAubrey witnessed Hervey Walter’s charter to Butley Priory, and also Rannulf de Glanville’s foundation charter to Butley. Peter Walter also held a close relationship with the third generation of the de Huntingfield family, descendants of Walter fitzAubrey. However, these close relationships could be due to the close proximity of their respective demesne manors.

Another likely candidate for this ‘Walter’ is Walter Arbalista/the crossbowman who held lands in Eye, as well as two lands nearby at Thrandeston and Brome where notably he was only named as ‘Walter’ in Domesday but identified as the crossbowman by his donation to Malet’s charter to Eye Priory of a manor situated in these lands (named ‘Gosewolde’), and the second adjacent to Shottisham (named ‘Halegestowe’- held in Domesday by Malet’s mother from Robert Malet, who must have given it to the bowman after his mother’s death), plus the church of St Margaret in Shottisham held by Walter the crossbowman. He was also a witness to Malet’s charter, indicating a close association with Malet, in which case, one would expect him to have held more lands from Malet than just those few attributed to him. So, therefore, the nearby lands in Bishops Hundred were quite possibly also held by him.

As will be explored in the following section on Walter the crossbowman, there is a possibility that he was also Walter de Glanville, which would explain the close association between the Walter family and the extended de Glanville family.

The last, less likely candidate who held lands in this same area from Robert Malet, including Stradbroke, Wingfield, and Chippenhall (Fressingfield), Horham and Chickering, was named Walter fitzGrip, however, he cannot be the same man named ‘Walter’ in several Domesday entries, as ‘Walter’ is listed firstly and separately to Walter fitzGrip, holding adjacent portions in some of the same entries and the way it is worded indicates two different individuals, which therefore increases the likelihood that ‘Walter’ is either Walter filius Aubrey, Walter de Caen or ‘Walter the crossbowman’ (possibly Walter de Glanville).

Eg. Stradbroke/Wingfield: “Walter holds from this manor 2 sokemen with 40 acres worth 8s in the same valuation. Robert de Glanville holds 4 with 20 acres 5s in the same valuation. Walter fitzGrip 1 with 15 acres, 30d. in the same valuation”.

However, again, an individual just named ‘Walter’, closely associated with either Malet or Eadric of Laxfield pre-Conquest, should also remain in consideration.

HOW MANY IN DOMESDAY WERE NAMED WALTER THE CROSSBOWMAN?

In the Domesday survey, the name of ‘Walter the crossbowman’ is listed as holding four lands as tenant-in-chief in Gloucestershire, and as sub-tenant of one land (Combwich) in Somerset from a prominent Domesday landholder Ralph de Limsey (in Normandy).

‘Walter the crossbowman’ also held the four lands in Suffolk from Robert Malet.

In comparison with the other crossbowmen listed in Domesday who held their lands in one county or adjacent counties, the distance between Gloucestershire and Suffolk in this instance would seem to suggest they were two distinct individuals, also taking into account the name of ‘Walter’ was so prolific in Domesday.

The fact that Walter held one of his lands in Somerset from Ralph de Limsey, and Suffolk from Robert Malet, may also support this argument. Walter the crossbowman in Suffolk held a close association with Robert Malet, as indicated by his donation to Eye Priory in Malet’s foundation charter which Walter also witnessed, however, Malet had no association with Somerset, which also appears to confirm that the Suffolk bowman was a different individual to that in Gloucestershire and Somerset.

WALTER THE CROSSBOWMAN OF GLOUCESTERSHIRE

Walterus Balistari held the four lands in Gloucestershire, at Bulley (Westbury), Ruddle (Westbury) and Ruddle (Bledisloe), and Frampton [Cotterell] (Langley) as tenant-in-chief, with much of the hundred of Westbury laying within the boundaries of the Forest of Dean. These lands appear to have reverted to the Crown at his death indicating he died without issue or he only had daughters, as there are no records of his issue continuing to hold his Gloucester lands. No records of the Westbury hundred court have been found and Westbury hundred belonged to the Crown, with the sheriff accounting for the profits of courts in 1169 with an income of 20s. received from the court. (Pipe Roll, 15 Henry II, 1168-69, p.117)

In the

Gloucestershire entries he was listed as Walteri Balistarius, in

comparison with the entries for the Suffolk lands where he was either listed as

Walter/Galter Arbalestarius, or just ‘Walter’.

WALTER THE CROSSBOWMAN OF SUFFOLK

In Domesday, Walterus

Arbalestarius/ the crossbowman, held lands in Suffolk under Robert

Malet, at Eye, Thrandeston and Brome in the Hundred of Hartismere, as well as

at Shottisham in the Hundred of Wilford.

Domesday entry

for Shottisham in Suffolk- Walterus arbalastarius- Shottisham

tenet Walterus arbalastarius de R. Malet’

Domesday entry

for Shottisham in Suffolk- Walterus arbalastarius- Shottisham

tenet Walterus arbalastarius de R. Malet’Domesday- translation

“In Thrandeston, Alweard, a freeman commended to Eadric held 36 acres as a manor TRE. Then and afterwards 1 plough, now 2 oxen 1 acre of meadow. It is worth 5s. The same Alweard holds from Malet. The king and the earl have the soke. In the same place 2 freemen, Godric and Leofstan commended to Eadric held 15 acres. It is worth 26d. Walter holds it from Robert.

In Brome, two free men commended to Eadric (of Laxfield) held 4 acres in the king’s soke worth 8d. The same Walter holds this (as Walter who holds Thrandeston).

In Thrandeston the same Walter holds 2 villans with 24 acres of the demesne of Eye, worth 4s.”

Halgestou near Shottisham (including St Margaret’s

Church)

In Domesday, Shottisham held by Walter the bowman;

Halgestou and Culeslea held by Malet's mother;

Sutton held by Walter de Caen & Walter filius

Aubrey; Laneburc held by 'Walter'

Alderton, Hollesley and Bawdsey held by Robert de

Glanville

(Bawdsey became the seat of Hervey de Glanville)

Walter the crossbowman in Suffolk donated lands and tithes he held in Suffolk from Robert Malet, at Halgestou, Gosewolde and the church at Shottisham, to Malet’s Foundation Charter to Eye Priory c.1103, to which he was also a signatory.

In several later

confirmation charters the gift is referred to as the ‘tithe of Walter the

arblaster’ without specifying a location (Eye cart., Nos.15,40,55), the

church being listed separately.

‘Goseweld’ or

Gosewould (Hall) is between Thrandeston and Brome. In Domesday, Thrandeston and

Brome, near Eye, were held by a ‘Walter’ and ‘the same

Walter’ from Malet- they have been attributed by scholars to Walter the

bowman due to his donation of Gosewold to Malet’s charter:

Eye Priory Charter No.1:

(Eye Priory Cartulary and Charters, 1, ed. V. Brown, pp.12-14)

Domesday Book

The entry for Shottisham in Domesday (Robert Malet as tenant-in-chief) (Domesday Book: A Complete Translation, pp.1214, 1216, 1212):

“Shottisham held by Walter the crossbowman from Robert Malet, which Osmund, a free man commended to Eadric (of Laxfield) held TRE with 44 acres as a manor and 1 bordar. Then 1 plough, now a half, 2 acres of meadow. Then it was worth 20s. now 10s. It is 7 furlongs long and 4 broad, 1 church with 13 acres worth 32d. In the same place, 12 free men commended to Eadric and 3 commended to Godric of Peyton held 80 acres. Then 3 ploughs now 1 ½; 1 acre of meadow. Then it was worth 16s, now 20s. Walter the crossbowman holds this from Robert Malet.”

Notably the surrounding lands of Hollesley, Bawdsey and part of Alderton (see map above) were held by Robert de Glanville, and the other part of Alderton and most of Sutton (just north of Shottisham) were held by Walter de Caen, all held from Robert Malet.

‘Laneburc’, east of Sutton (held by ‘Walter’) and north of Shottisham, was a small holding of 5 acres worth 12d., which ‘Walter holds in demesne’. (This cannot be assigned to a particular Walter, but probably de Caen.)

Domesday Book (: A Complete Translation, p.1213) - EYE:

“Eadric held Eye with 12 carucates of land held TRE: now Robert Malet holds it in demesne and his mother holds 100 acres. To this manor belong 48 sokemen with 121 acres of land. Of these sokemen 37 are in demesne. Herbert (viz. Hubert, 1st prior of Eye Priory) holds 9 with 20 acres, and Walter 1 with 5 acres and Walter the crossbowman 1 with 16 acres. All this is worth 9s. In the same vill 1 freemen Wulfric commended to Eadric held 30 acres as one manor TRE: now Walter de Caen holds it from Robert.”

Given Walter the bowman’s close association with the Malet family, as evidenced by his donation to Malet’s charter which he also witnessed, it would seem most likely that Malet would have granted him more lands than just the four attributed to him, so it could be highly likely he was the ‘Walter’ who held lands at Wingfield/Stradbroke, Weybread and Chippenhall/Fressingfield, Laxfield, Badingham, etc, all part of Malet’s Honour of Eye, and close to the other lands held by the bowman. And as is found in the entries for Wingfield etc, Walter the crossbowman was just listed as ‘Walter’ in Thrandston and Brome.

Vivien Browne in her Eye Priory Cartulary and

Charters II (p.65) wrote about Walter the arbalister and the lands in

Suffolk:

p.71-72: Gosewolde

in Thrandeston. Walter the arblaster gave two thirds of his tithe in

Gosewolde. In 1086, he held one freeman with 16 acres belonging to the manor of

Eye, and Gossewold Wood or Goosewood is listed as a parcel of the manor of Eye

in 17th century surveys. The tithe was confirmed by bishop Ralegh in

1242 (Charter 42) and in 1254 and 1291 the tithe, worth 5s., was listed in the

parish of Thrandeston and pertained to the sacristan. The 1308 list includes

the tithe of bracken, pannage and agistment of cattle in Gosewolde (No.396) the

name is preserved to the present day in Goswold Hall, Thrandeston.

p.49: Shottisham,